Fortifying Galle Fort

Conservation of the gun platforms of the Neptune Bastion

As restrictions around the pandemic eased this month, a team of workers returned to Galle Fort. They are in the middle of a two-year restoration project that has them clambering over the great bastions, excavating echoing underground chambers and clearing out an ancient drainage system – all part of an ambitious effort to restore this UNESCO World Heritage Site to its full glory.

By the time they’re done, sometime in early 2021 the Fort will welcome visitors to explore areas that have been locked away for decades, and will include exacting replicas of some 36 cannons in 21 sites,extensive new signage and planned walking trails, as well as carefully restored ammunition bunkers and vaults from the British, Dutch and Portuguese periods. At night, a system of lighting will set the entire Fort glowing like a jewel – a testament to its status as one of Sri Lanka’s most visited attractions.

Nilan Cooray

Nilan Cooray, a conservation specialist and team leader for the consultancy team, explains that the project falls under the national effort known as the Strategic Cities Development Program (SCDP) which is led by project director K. A. D. Chandradasa. SCDP is focused on revitalising major urban centres outside Colombo. Drawing on World Bank funding, the project at Galle Fort has two components, which are essentially the conservation of the defence works, and what they are calling ‘interpretive visitor presentation.’

Work began in 2019, as teams went in to evaluate the Fort’s 14 bastion walls. Some of these date back to the 16th century, when Portuguese rulers erected the first of the fortifications. Subsequently, in the 17th century, the Dutch added to and extended these fortifications, creating a formidable rampart. When the British followed, they added their own structures and weapon systems, and renamed the Triton, Aeolus, Neptune and Aurora bastions in honour of the Royal Navy ships which helped them seize Ceylon during the Napoleonic Wars.

Workers conserving the seaside walls of the Black Fort (Zwart Bastion)

Today, the bastions still loom over the cobbled streets of the Fort and you can trace their length from the Zwart bastion (believed to be the only surviving remnant of the original Portuguese fortifications), to the Point Utrecht bastion (where you’ll find the lighthouse) and on to the Aeolus and Star bastions, which are now part of a military base.

“It’s amazing to think that they built these monumental ramparts without the technology and materials we take for granted today,” says Cooray, painting a picture of the logistical challenges the builders faced. They were also working under pressure – having to stay vigilant for attacks from the sea, where other European powers rode the ocean waves, waiting for an opportunity to attack.

Having not only outlasted the colonialists, but survived a civil war and a raging tsunami, the bastions are now a little worse for the wear, Cooray explains, adding that as part of the project they will be restoring collapsed sections associated with the Star and Akersloot bastions, as well as the underground drains that run through the ramparts, which have long since collapsed or been blocked up by debris.

The team will even go outside the Fort to shore up the ramparts from the sea side, stacking boulders against their bases to prevent ongoing erosion. Cooray says this last measure is critical as climate change is already seeing sea levels rise along our coast. “Some might wonder whether we should be putting in all this effort and money to preserve construction done by invaders,” says Cooray, “but in truth the materials were all from here, and the people who actually built this were Sri Lankan, so this is also part of our heritage.”

Interior of a vaulted gun powder magazine after conservation

There is also value for the local economy in drawing tourism dollars. A UNESCO World Heritage site since 1988, the Galle Fort consists of many ‘historical layers’ explains Cooray. “We think of this as a Dutch Fort, but of course you still have elements remaining from the Portuguese period, and the British also added new constructions including military installations such as bunkers as well as the lighthouse and clock tower. We want to highlight this aspect of it as well.”

These distinctions are reflected in the construction and military equipment deployed in the Fort. Powder magazines, ammunition bunkers and vaulted passages were built underground to ensure that if something did explode, it wouldn’t do too much damage. Those built by the Dutch tend to be large, reflecting the size of the weaponry at the time. By the British period, the ammunition bunkers had shrunk, with modern weapons requiring less in the way of space. Builders also had new materials, like cement, at their disposal.

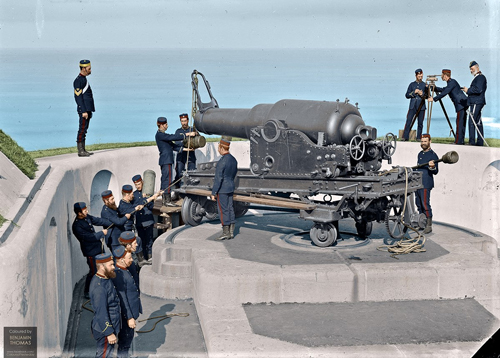

The actual weaponry has long been missing. Cooray says that despite extensive research they have been unable to locate the original cannons and some of the only traces remain in photographs from the period. Perhaps they were moved to alternate sites in the pre-independence years. However, the circular rails that were installed to rotate coastal artillery guns remain.

Image of the artillery gun and the carriage planned for replication at Triton Bastion

Working with the British embassy and accessing their archives, Charmikara Pilapitiya, SCDP’s consultant on historic cannons and artillery guns, was able to identify the original models. The goal now is to cast faithful replicas using a mix of fibre resin and dolomite chips to recreate the granular details, including the colour, texture and even the weight of the weapons, to give visitors a convincing glimpse of history. They will also be fashioning models of gun powder barrels, tools used in the process of firing the cannons, cartridges, swards, hand guns and other accessories, and placing them in the underground bunkers. Visitors to the new site will be provided plenty of context and information.

“This will be the first time in Sri Lanka that such a programme is being implemented to provide the general public about the wide range of cannons and artillery guns that were used during Portuguese, Dutch and British Period,” says Cooray.

The team hopes to cross the finish line by February next year. For Cooray, the project has brought with it many pleasures, but he is particularly pleased to think of what it will mean for the local community. The last time he visited, he went up onto the ramparts. Looking around he saw their green terraces crowded with children flying kites and families taking in the stunning views. This sense of living history is what makes this place special in Cooray’s eyes. Now, he says, he wants to ensure it stays that way: “If we can conserve this historical site well, it will add value for these people, and give this area a new lease of life.”