Sri Lanka has become a poorer nation!

View(s):

The per capita income of Sri Lankans will fall this year too.

Last year 2019, Sri Lanka became a poorer nation than what it was in the previous year.

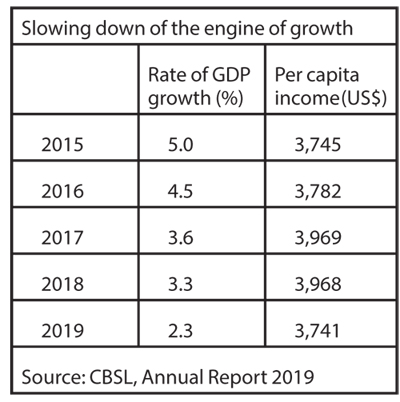

From the average annual income of each Sri Lankan, US$227 got wiped out. This is because the per capita income was $3,741 in 2019, compared to $3,968 in 2018. Interestingly, Sri Lanka’s per capita income level in 2019 was just only $4 ahead of the figure five years ago in 2015.

What an achievement and how did this happen. One might point the finger to the Easter Sunday attack in April 2019 and another to the 52-day-government saga in October 2018. Whichever the reason and finger pointing to explain the fall in income, they all point to our own faults rather than anything else.

Last year was not an exception either in declining income. In 2018, Sri Lanka has added only $1 to the per capita income of its people from the 2017 figure.

With falling income levels in the economy, the country must have slipped away from its “upper-middle income” status back to the “lower-middle income” status. It was only last year on July 1 that the World Bank declared that Sri Lanka has graduated from lower-middle to upper-middle income category. And within six months since then, we are back to lower-middle income category status again.

Calculations and statistics

Per capita income is calculated from gross national income (GNI), and not the gross domestic product (GDP). There is a conceptual difference between the two measurements. GNI includes all incomes earned by the “people of Sri Lanka” irrespective of where they earned it. This means that even Sri Lankans with earnings outside Sri Lanka are counted in the GNI. In contrast, GDP accounts for all incomes earned by “people in Sri Lanka” irrespective of the fact whether they are Sri Lankans or not. This means that earnings of anyone within Sri Lanka are counted for the GDP. It is, therefore, clear that the difference between the GNI and GDP is made up of net primary income from abroad.

The very basic determinant of per capita income level and its progress is the rate of economic growth. Over the past five years Sri Lanka’s rate of economic growth has reported a steady decline from 5 per cent in 2015 to 2.3 per cent in 2019. For this fundamental reason underlying the slowing down of the engine of growth, there is nothing to be surprised with the dismal performance of per capita income and, finally its fall last year.

From a statistical point of view, per capita income figures are sensitive to three measurements – population growth, inflation rate and exchange rate movements. As per capita income is measured by dividing GNI with the population of the country, a slower population growth in some countries allows higher growth in per capita income. Sri Lanka has a slower population growth – less than 1 per cent a year, so in a real sense we should have a higher per capita income growth. In that context, what we have seen is more than disappointing.

From a statistical point of view, per capita income figures are sensitive to three measurements – population growth, inflation rate and exchange rate movements. As per capita income is measured by dividing GNI with the population of the country, a slower population growth in some countries allows higher growth in per capita income. Sri Lanka has a slower population growth – less than 1 per cent a year, so in a real sense we should have a higher per capita income growth. In that context, what we have seen is more than disappointing.

GNI is measured in “nominal” terms using the current market prices. If a country is running a higher inflation rate, then the GNI value in nominal terms rises even without a substantial real rate of economic growth. Thus, GNI inflated by the higher rate of inflation can appear as an improvement, whereas it is not. For international comparisons, GNI is converted to US$ terms using the exchange rate. In a country where the exchange rate appreciates, then automatically the per capita income gets inflated.

The most recent experience of Sri Lanka with higher inflation and exchange rate appreciation was in the 2000s, prior to the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. Both the higher inflation and exchange rate appreciation led to an inflated per capita income figure too. Therefore, the per capita income figures should be understood with some caution.

Outlook for 2020

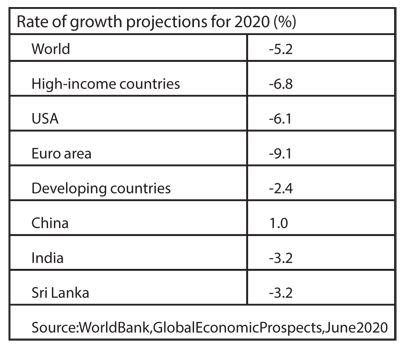

While Sri Lanka became poorer last year, the same thing will be repeated this year. This is not connected to local events last year but for a valid reason that has affected the global economy. According to the World Bank’s growth projections in Global Economic Prospects (June 2020), the world economy is bound to contract by 5.2 per cent this year, which has never been the case of the known history of the modern world.

The economies of the rich countries are estimated to contract by 6.8 per cent, compared to 3.2 per cent contraction in 2009 when the global financial crisis occurred. A special feature of the global recession this year is that developing countries are set to contract by 2.4 per cent. Although their growth slowed down during the time of the global financial crisis, the growth rates didn’t turn to negative figures; they still continued to grow. But this time it is different as the entire world, both rich and poor countries are going to suffer a global recession in 2020 emerging out of the COVID-19 pandemic issue.

The economies of the rich countries are estimated to contract by 6.8 per cent, compared to 3.2 per cent contraction in 2009 when the global financial crisis occurred. A special feature of the global recession this year is that developing countries are set to contract by 2.4 per cent. Although their growth slowed down during the time of the global financial crisis, the growth rates didn’t turn to negative figures; they still continued to grow. But this time it is different as the entire world, both rich and poor countries are going to suffer a global recession in 2020 emerging out of the COVID-19 pandemic issue.

According to World Bank projections, Sri Lanka’s rate of economic growth is negative, showing a contraction by 3.2 per cent, which we have never experienced during our post-independent history. Even if this growth projection is reliable, we still have half the year to influence growth and change the trend. However, the pain of the slump of economic growth is severe not only because of the COVID-19 pandemic issue, but also because of the dismal growth performance in the past prior to the pandemic problem.

Recovery and take-off

Sri Lanka’s current growth trajectory comes from three channels: Firstly, it is the adverse economic impact of the lockdown approach that Sri Lanka has adopted. Secondly, it reflects a breakdown of the country’s global connectivity affecting the economy. Even if Sri Lanka can return to some degree of normalcy by eliminating the community spread of the pandemic, returning to normalcy in isolation does not mean much in terms of the country’s economic recovery. The differences in the sequencing of the spread of the pandemic in different regions would still constrain the recovery in individual countries. Finally, the negative impact of the crisis is not only because of the pandemic issue, but also the global economic crisis which now appears to be much deeper and wider than initially thought. This means that even if the COVID issue is over, the global economic crisis that has followed and the resulting shift in economic policies will continue to deter the growth prospects of countries like Sri Lanka.

Sri Lanka’s current growth trajectory comes from three channels: Firstly, it is the adverse economic impact of the lockdown approach that Sri Lanka has adopted. Secondly, it reflects a breakdown of the country’s global connectivity affecting the economy. Even if Sri Lanka can return to some degree of normalcy by eliminating the community spread of the pandemic, returning to normalcy in isolation does not mean much in terms of the country’s economic recovery. The differences in the sequencing of the spread of the pandemic in different regions would still constrain the recovery in individual countries. Finally, the negative impact of the crisis is not only because of the pandemic issue, but also the global economic crisis which now appears to be much deeper and wider than initially thought. This means that even if the COVID issue is over, the global economic crisis that has followed and the resulting shift in economic policies will continue to deter the growth prospects of countries like Sri Lanka.

At this crucial hour, the country needs to look beyond monetary and fiscal stimuli and beyond the temporary import controls in order to prepare for not just the recovery, but the take-off. What it requires is the removal of the obstacles in the past that have constrained the country’s higher growth performance.

(The writer is a Professor of Economics at the University of Colombo and can be reached at

sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk).