News

Strong plea to strengthen grass-root Primary Medical Care Units to face post-COVID-19 era

A mother with a five-year-old child who has fever, cold and cough goes to the Outpatients’ Department (OPD) of a state hospital on a Monday morning. The child has been ill for a day, the OPD doctor examines the child, prescribes some medicine and the mother and child go home.

By Tuesday evening, the cough is worse, so the mother consults a private General Practitioner (GP) as she feels that the OPD doctor did not pay much attention to the child. The GP examines the child and orders a Full Blood Count (FBC), if the fever does not clear and gives some medicine.

Prof. Kumara Mendis

By the next day, the fever is higher and by evening the mother channels a specialist at a private hospital. The specialist recommends that if the fever has not settled by evening the next day, the child should be admitted to hospital. The child is admitted to a state hospital. When the illness worsens with vomiting and the presence of a rash, the child is diagnosed as having Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever (DHF), admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), treated and discharged.

It is through this simple tale – a reality enacted daily across the country – that Prof. Kumara Mendis, Chair Professor of Family Medicine of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, explains how ‘primary’, ‘secondary’ and ‘tertiary’ care is administered to people.

This is also why Primary Medical Care Units (PMCUs) which are at the very grassroots need strengthening to meet future challenges such as COVID-19, it is learnt.

The health structure is as follows:

n Primary care – this is what the mother had with the OPD doctor and the GP. Prof. Mendis explains that when people consult doctors in the ‘ambulatory’ (outside a state hospital) setting, they get ‘first contact care’ through a GP or at an OPD. If they are to be referred to secondary care, there should be a referral system in place.

n Secondary care – this is provided in state hospitals under different specialities such as general medicine; surgery; obstetrics & gynaecology; paediatrics and psychiatry.

n Tertiary care – all the niche specialities such as intensive care, neurology and cardiology etc., fall under this category.

Delving into the situation created by the COVID-19 outbreak, Prof. Mendis stresses that most of the guidelines Sri Lanka has for COVID are for hospital doctors.

Regrettably, these guidelines are issued on the assumption that they would cover both the OPD and the wards, but he points out that in some recent 47-page guidelines, there is less than one page specifically for the OPD, where COVID-19 or non-COVID-19 patients have first contact.

“The successes with regard to curbing the spread of COVID-19 up to this point are mainly due to the preventive arm of the public health state system. The primary healthcare (PHC) system has two arms, with ‘prevention’ being carried out by the Medical Officers of Health (MOHs) and their staff and the ‘curative’ arm being handled by primary medical care units at the very grassroots,” he says.

Commending the PHC system, Prof. Mendis heaps appreciation on MOHs and Public Health Inspectors (PHIs) who have performed their duties “beyond” expectations. “Even now, I am 90% sure that there is no community spread.”

The Assistant Registrar of the Sri Lanka Medical Council (SLMC), Dr. Chandana Atapattu adds his voice to the plea to strengthen primary care, while looking at the small-time GPs who at grass-root level conduct their practice in a small space which consists of a tight waiting, consultation and dispensary area.

There are three key features in the provision of primary care – ‘first contact care’ (a person walks from his/her home to the closest doctor, who is sometimes referred to as the ‘family doctor’); ‘continuity of care’ (this too is provided by the family doctor); and ‘holistic care’, he says.

Dr. Chandana Atapattu

Citing the differences between the care given by a family doctor and a specialist when seeing a person with asthma, Dr. Atapattu says the family doctor would know the patient and his/her history well, whereas a specialist would prescribe some inhalers for the specific problem. Therefore, it is the family doctor who provides holistic care.

Next the Sunday Times gets a view of the primary healthcare facilities available in the country. In the government sector, the main providers of primary healthcare are 499 PMCUs (earlier called central dispensaries) with each staffed by a doctor. The next level is the 472 Divisional Hospitals (earlier called rural hospitals, peripheral units or district hospitals). There are also Base Hospitals, General Hospitals and Teaching Hospitals which have OPDs which also provide primary care.

In the private sector, there are GPs, family doctors and family physicians, all tallying up to about 250 full-time, while more than 10,000 doctors work in the state sector during office hours and engage in private practice after hours, who provide primary care, says Dr. Atapattu, pointing out that then there are also specialists providing channel consultations as first contact care.

According to the annual health bulletin, there are 100 million visits to primary care doctors, says Prof. Mendis, analyzing this figure as one person (when taking a 20 million population) seeking such treatment five times per year on average.

Of these 100 million visits, 55% are private primary care consultations and 45% in the government sector. It is estimated that by 2027, the 100 million visits will increase to 200 million. “The sad plight is that there is simply no medical record, not even a small slip, of all these visits except a prescription given to the patient which most probably gets misplaced after a few days. Only the GPs would have a file of their patients, maybe for about 5-10%, and those will not be computerized records,” he adds.

Their urgent plea is that in view of the dangers that the world and Sri Lanka are facing due to COVID-19, there is a need to strengthen what the country already has in place in the primary care setting.

Dr. LakKumar Fernando Sri Lanka needs to consider the false negatives, strengthen public preventive measures and ramp-up testing How should the country move into the ‘new normal’ future, essentially living with COVID-19? A dengue expert, who along with a few others changed the management of that mosquito-borne viral disease in Sri Lanka, has come up with some relevant suggestions. In an interview with the Sunday Times, the Clinical Head of the Centre for Clinical Management of Dengue & Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever, Negombo & Consultant Paediatrician, Dr. LakKumar Fernando, discussed some “newer” thoughts about the new coronavirus: the exit strategy vs living with COVID-19. Before focusing on Sri Lanka, Dr. Fernando glances at other countries, while reiterating that COVID-19 being a new disease, the world is on a “big” learning curve. This means that strategies need to be changed based on new information, he says. n When Singapore had 8,000 tested positive cases, there were only 11 deaths. n When China had 80,000 cases and 4,000+ deaths, its case number may have been 8 million, as it did not do extensive testing those days. n Italy’s testing was very low and its death rate was shown as 10%. n Germany, however, with more testing ended up with a 0.4% death rate. n At that time, Sri Lanka had 250 cases and 7 deaths. It did not mean Sri Lanka was 20 times worse than Singapore in treating patients. If at all, Singapore may be twice better than Sri Lanka. n If Sri Lanka had 7 deaths, maybe our corresponding case number was 3,000-5,000. If many people have recovered, maybe Sri Lanka has 2,000-3,000 active cases now. Has the community spread of COVID-19 begun in Sri Lanka? Dr. Fernandobelieves that low-grade community spread has begun. The example he cites is a location like the highly-congested Bandaranayake Mawatha in Gunasinghepura. This is his analysis: If such a location has 2,000 people, all were tested for COVID-19 through RT-PCR (Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction) and there were 60 ‘positives’, the chances are that there could also have been 40 ‘false negatives’. This is because when nasopharyngeal samples are taken for the RT-PCR test, the virus would be found within the samples only in about 60% of the cases, when it is done by trained staff in a laboratory setting. However, these samples are not being taken under ideal conditions. As such the ‘false negativity’ could be even higher than 40%. The next step is to admit the 60 ‘positive’ people to hospital and carry out contact tracing of all those who associated with these patients. The balance 1,940 people, who are in quarantine would be released back to the community after 14 days, under the assumption that they would develop symptoms if they have the virus within those 14 days. But current data show that more than 95% will be largely asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic. This means that when they are released to the community, at least 40-50 among them could continue to spread the disease even without symptoms. The two solutions for this are: n The affordable solution is to be realistic and tell the people that there could be a number of asymptomatic people around them who could spread the disease and minimize spread by installing very serious precautionary measures. n Finding ways to correctly identify the ‘false negatives’ and do contact tracing for them as well. These could be by ramping up testing. In a low-resource setting like Sri Lanka, in addition to RT-PCR testing, the place for other options should be properly evaluated. These options which should be evaluated are the newly-emerging rapid antigen testing (to save time and cost) and using sensitive antibody testing after 14 days. The antibody test would be to identify the extent of infection-spread in the community.

| |

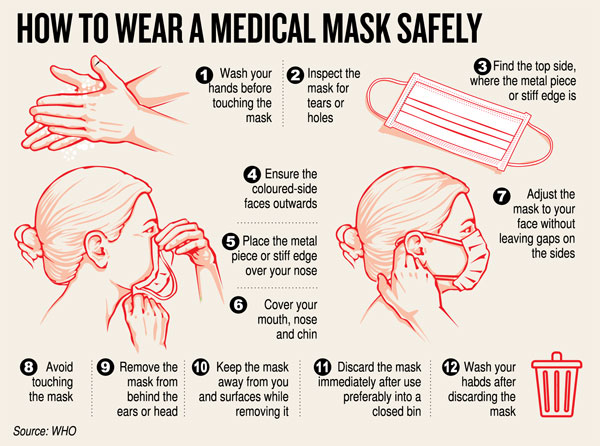

| The way forward after curfew & lockdown n Open up districts which have had no infections but with strict monitoring and absolutely no border-crossings. n The people need to strictly adhere to social distancing and hand-washing. Hand-washing facilities should be mandatorily installed at all institutions, public or private, and also public places such as banks, bus-stands, railway stations, marketplaces and shopping malls. n All people (inclusive of those who are asymptomatic) to mandatorily wear face-masks, be it even cloth. All people need to be educated on how to wear the masks properly. n Testing has to be ramped up exponentially, at least 10-fold, in the community and in quarantine centres. This is to identify as much as possible anyone who is infected as early as possible and have a system in place to stop that infection from spreading to others. n Gradually, the districts around the opened districts can follow suit, but once again under strict monitoring. If there is the slightest indication that the infection has re-emerged, then those areas need to be closed immediately.

|