News

Deep in Sinharaja, hope rises for threatened jumbos

A hazardous operation to radiocollar one of the last remaining elephants of the Sinharaja rainforest has given new hope that both elephant and human lives can be saved when the two species collide.

The elephant was radiocollared on June 1 by the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) following a strenuous operation in mountain terrain amid leech-infested rainforests.

Signals transmitted every four hours by the GPS collar show the elephant, known as Panu Kota, travelled 52km over the last two months (55 days), crossing two mountain ranges, the DWC’s Director of Veterinary Services, Tharaka Prasad, said.

Dr, Prasad said the signals could be used for “geofencing”, giving warnings if an elephant crosses the border of a village.

He explained that a geofence is a virtual perimeter that can be pre-set on the application that uses to monitor elephant movements.

For example, a geofence can be set encircling a village so that whenever an elephant crosses that boundary, an SMS is transmitted to those monitoring the elephant’s movements. This message can be relayed to local DWC staff who can rush to the area and chase the animal back into the forest.

Dr. Prasad said his officers are still working on the geofencing facility and, once set up, it would be an invaluable tool to manage the Sinharaja elephants.

The collaring of Panu Kota was carried out with help from the Eco-system Conservation and Management Project (ESCAMP) through a project funded by the World Bank that will see 40 elephants collared in order to better understand their habits and reduce human-elephant conflict, Dr. Prasad said.

Historically, Sri Lanka’s wet zone rainforests teemed with elephants, but now only two, Panu Kota and Loku Aliya, both males, remain in the Sinharaja Forest Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage. A female that had not been sighted for some time is believed dead.

Incursions into villages over the years by these elephants have cost 16 human lives, and last year villagers campaigned for the animals to be moved to another area.

The then minister of Wildlife Conservation, Sarath Fonseka, initially supported the villagers’ demand to relocation but this provoked environmentalists who wanted the elephants to be left free to roam.

The DWC then decided to attempt using radiocollars for geofencing.

After being tracked for several days, Panu Kota was sedated by a team led by the area wildlife ranger, Kapila Ranukkanda, and veterinary surgeon, Malaka Abeywardena, in an area known as Dole Kanda.

Wildlife officers worried about how to safely sedate the lonely jumbo in difficult terrain. When an elephant is shot with a sedating dart it must be followed to make sure it does not fall awkwardly and suffocate through having its lungs blocked. If that happens, wildlife vets would have to immediately employ the reversing drugs to get the animal back on to its feet – a dangerous operation.

“We opted for a less powerful drug to sedate the jumbo,” Dr. Abeywardena said, adding that this would increase the risk for the team that followed the elephant but decrease the risk to the elephant.

Panu Kota had a gunshot wound in one of its legs and the team used the opportunity to treat the injury, Dr. Abeywardena said. He estimated Panu Kota could be 35 years old.

Nisal Pubudu, a tea inspector in Pothupitiya, says most villagers in the area loves the animals, seeing them as a source of pride for their area.

When a DWC team caught Panu Kota in 1999 to relocate him, villagers, particularly students at Kajuwatta School, protested and forced the release of the elephant.

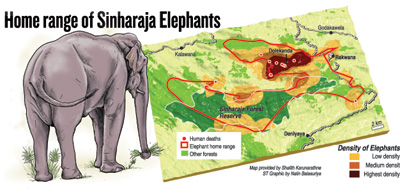

The home range of the Sinharaja elephants could extend to 22,853 ha, spilling outside the protected area, said Shalith Karunaratne, a young graduate of the University of Sri Jayawardenapura who studied the rainforest elephants.

The elephants roam in seven secretariat divisions covering Kalawana, Kahawattha, Godakawela, Kolonna, Neluwa, Kotapola, Nivithigala, and 29 grama niladari divisions.

Mr. Karunaratne’s research, conducted with the support of ranger Kapila Ranukkanda, shows both the elephants moving around the Dolekanda, Rambuka, Rakwana South and Kathlana Grama niladari divisions from March to July when they are in musth and become aggressive.

At other times, they roam mainly in forest-edge habitats and, at the end of August, the elephants head towards the Morningside cloud forest area of Sinharaja.

This year, no deaths have been reported due to the elephants’ presence, and activists praise wildlife officers for their proactive measures to chase the elephants back into the forest whenever they are reported in villages. The radiocollaring data is expected to paint a more accurate picture about the elephants’ movements.