News

Don’t frighten leopards out of existence

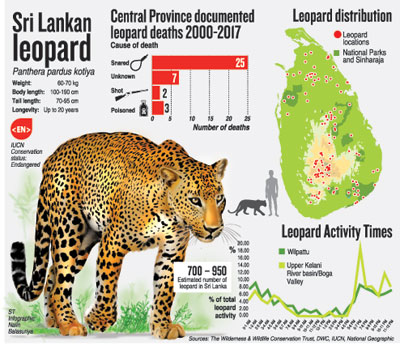

Last week’s commotion over a cornered leopard reinforces the need to handle such encounters with care to prevent an escalation into intense leopard-human conflict, warn experts Andrew Kittle and Anjali Watson.

A few close encounters with leopards occur every year in the hill country; last week’s incident was at the Panmore tea estate in Hatton.

There are many versions of the story but according to local sources it began when a female tea plucker came upon the leopard at night while it was feeding on a dog it had killed.

Caught by surprise, the leopard sprang past her, causing minor injuries. It withdrew to a nearby forest patch while fellow estate workers and management came to her aid.

Estate workers called the police and the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) officers to the scene and wanted the animal captured immediately.

Free-ranging leopards are not tranquillised except as a last resort as the pain inflicted by the dart could frighten the leopard into leaping out of range of capture and because the animal could die if drugs to reverse the tranquilliser were not administered in time, according to DWC chief veterinary surgeon Dr. Tharaka Prasad.

The wildlife officers explained this to the estate workers and promised to set up a cage trap to capture the animal in days to come. The workers wanted the DWC to seize the leopard then and there and take it away.

The mob become unruly and began trying to chase the leopard away.

The cornered leopard, in fear of its life, sprang out of its hideout and in its attempts to escape injured five estate workers.

A few days later, the DWC set up a cage with bait but the leopard has not visited the area since then, perhaps more traumatised by the incident than the people who were injured.

Leopard researcher Anjali Watson emphasised that leopards always try to avoid encounters with people. “If the tea plucker made a noise, making her approach clear, the leopard would have stealthily retreated, avoiding the encounter,” she said.

“Almost all the leopard incidents in these areas happen due to the animal being surprised or when mobs try to chase a leopard.

“There have been no incidents of a leopard stalking a human with intent to kill,” Ms. Watson said.

Through the Wilderness and Wildlife Conservation Trust, Ms. Watson and Dr. Kittle have been conducting research on leopards in the hill country since 2011 as understanding their ecology is the key to protecting them.

They have observed how leopards live outside protected areas and have adapted well to living even in habitats close to human settlements. Leopards inhabit a wide variety of landscapes in the hill country, from large intact forest swaths to small (less than 5 sq km) isolated patches of heavily degraded secondary forest.

“The leopard is amazingly adaptable and can live in a wide variety of habitats given an adequate prey base and some sort of vegetative cover,” Dr. Kittle said.

In the hill country, leopards roam a range of landscapes including established and regenerating forests, forest plantations of eucalypt and pine, tea estates and areas near human settlements.

Most of the national parks of the country are within the dry/arid zone; the montane (mountain) zone currently has only one declared park (Horton Plains), one Strict Natural Reserve (Hakgala) and three other protected areas of lesser status (Peak Wilderness Sanctuary, Pedro Forest Reserve and the Knuckles Range (currently undergoing status change).

Although some small forest reserves are interspersed throughout the zone these areas have not been considered wildlife refuges, let alone leopard habitat.

Large tracts of wilderness in the sub-montane and montane zones were cleared and cultivated into coffee and tea plantations in the late 1800s under British rule. This greatly reduced the extent of forest cover but higher montane forests (higher than 1900m) still exist and are used by leopards.

Sadly, more and more highland forests are being cleared for agriculture, forcing leopards to use areas closer to human settlements. It is mostly the males, particularly the young ones, that roam around while females prefer to stay in the forest patches, according to the researchers.

Leopards have learned to become elusive creatures to avoid encounters with humans. One sign of this is that they are active at night, particularly outside protected areas.,

There are two spikes of activity: early in the morning as leopards retreat to their hideout forest patches, and just after nightfall, when they come out to look for prey and mark their territories.

In the highlands, this nocturnal behaviour is even more pronounced in comparison to dry zone study sites. Researchers warn estate workers to be extra careful at these times and to make enough noise when approaching leopard habitat to avert unexpected encounters.

When there is an incident people want the animal relocated but translocating wildlife, especially top predators such as the leopard, should only be used as a last resort, Dr. Kittle said.

Wild animals, particularly higher order mammals such as the leopard, know how to survive in their native habitat from the experience of having grown up there.

Transfer to an alien habitat usually results in the inability of the animal to adapt to its new surroundings. A new prey base, new competitors and the potential of a new climate can have tremendously adverse effects on survival potential.

Moving a leopard from the hills to Yala, the Knuckles Range or even to Horton Plains, for instance, is unlikely to be successful given these areas already have resident animals who would not welcome a new arrival. Well-documented Indian studies show that translocating leopards is unsuccessful, with high leopard mortality, Dr. Kittle said.

Despite knowing this the DWC is sometimes forced to take the difficult option of translocation to prevent the leopard being killed by worried residents.

Ms Watson recalled an incident that shows the difficulties faced by wildlife officials. A leopard fell into a well in Nawalapitiya in 2011; the researchers and wildlife officers wanted it rescued and released into nearby forest patches but local villagers vehemently protested.

It was not easy for wildlife officials to find a suitable alternative habitat as leopards, especially males, are territorial, and introducing a stranger into another’s territory could result in fights that could be fatal. The loser might be forced to find living space elsewhere and could stray into more populated areas, instigating conflict with humans.

Ultimately, the researchers and wildlife officers selected the Kandapola forest reserve in Nuwara Eliya. An adult male leopard had been killed after having been caught in a snare there some months previously so the researchers felt the area was available for another male to claim it as its territory.

Most people want such animals rescued and to survive – a praiseworthy attitude that has allowed Sri Lanka to still have so much wildlife within its tiny borders – yet often they do not want them in their backyards even though these backyards are, in fact, forest.

Older villagers who are used to living together with wildlife are usually willing to allow a leopard to remain in its habitat nearby: it is often newcomers, formerly from urban areas, who are unwilling to live in co-existence.

The Wilderness and Wildlife Conservation Trust and wildlife department conduct community awareness programmes in border settlements and tea estate communities to help reduce human/animal conflict.

“You cannot conserve leopards by restricting them only to protected areas. Protecting their habitats and co-existence will decide this magnificent creature’s future,” Ms Watson pointed out.

Plantation companies are supportive of protecting biodiversity in their estates, she said.

The WWCT team conducts its research work from the Dunkeld Conservation Station, which was set up in partnership with the Resplendent Ceylon/Dilmah Conservation and sits within the Dilmah tea estate, Dunkeld, in the Dickoya area.

“This partnership is an example of the positive attitude the tea management companies and private estate owners in the region have towards leopard conservation in the highlands.

“It is through such collaborative partnerships and working together with these estate management and the workers that the conservation of Sri Lanka’s highland leopard can occur,” Ms Watson said.