Looking at a lizard through literature

My work as the Sri Lanka English consultant to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) involves collecting as many published references as possible to the 200 and more words of Sri Lankan origin contained in the dictionary. The start date for these references is 1681, the year the first book on Ceylon in English appeared in London. With the chronological reading of these references it is possible to antedate the earliest known use of a word, check on any changes in definition, and chart the variant spellings that often occur along the way. The more important references may then be reproduced in the revised OED entry for the word concerned. In this manner the dictionary provides an historical perspective rare in lexicography.

My work as the Sri Lanka English consultant to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) involves collecting as many published references as possible to the 200 and more words of Sri Lankan origin contained in the dictionary. The start date for these references is 1681, the year the first book on Ceylon in English appeared in London. With the chronological reading of these references it is possible to antedate the earliest known use of a word, check on any changes in definition, and chart the variant spellings that often occur along the way. The more important references may then be reproduced in the revised OED entry for the word concerned. In this manner the dictionary provides an historical perspective rare in lexicography.

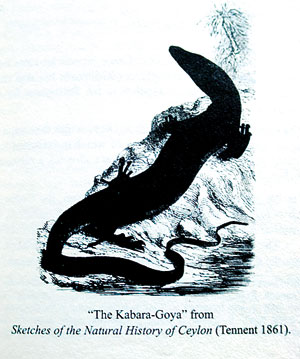

A spin-off has been that I have ended up with batches of references that not only provide the history of words, but also, because the words are all nouns, considerable and often fascinating descriptive information about the fauna, flora, inanimate objects, etc., they represent. One of my favourite examples is kabaragoya, the watermonitor, up to two metres in length that has always fascinated the uninitiated with its size and crocodilian appearance.

Today, a fairly common experience is the ‘saurian show’, which occurs when a kabaragoya decides to cross the road in its inimitable slow and lumbering fashion. This necessarily causes traffic to slow, weave, or often stop altogether, thus providing an excellent view of an awesome creature and the possibility of a great photo.

Over the past few centuries there have been many references to the kabaragoya in English literature pertaining to the island, but, being a difficult name for outsiders to digest there have been extraordinary variant spellings such as kobberaguion, kobberagoya, cobra-coy, cobra guana, kabara-godho, kabara, cabragoya, cabaragoya, and kabareya. Some of these will be found in the select references I reproduce below chronologically to describe this lizard through literature.

The earliest reference in the OED entry is by Robert Knox from An Historical Relation of Ceylon (1681): “There is a Creature here called Kobberaguion, resembling an Alligator. The biggest may be five or six feet long, speckled black and white. He lives most upon the Land, but will take the water and dive under it: hath a long blue forked tongue like a sting, which he puts forth and hisseth and gapeth, but doth not bite nor sting, tho the appearance of him would scare those that knew not what he was. He is not afraid of people, but will lie gaping and hissing at them in the way, and will scarce stir out of it. He will come and eat Carrion with the Dogs and Jackals, and will not be scared away by them, but if they come near to bark or snap at him, with his tail, which is long like a whip, he will so slash them, that they will run away and howl.”

Being such a remarkable reptile, there are many later references to the kabaragoya in English literature. The first reference after Knox, some 140 years later, is by Amelia Heber in Reginald Heber’s Narrative of a Journey (1825): “In a valley, near the road side, I saw a Cobra Guana: it is an animal of the lizard kind, with a very long tail, so closely resembling an alligator, that I at first mistook it for one, and was surprised to see a herd of buffaloes grazing peacefully around it. It is perfectly harmless, but if attacked will give a man a severe blow with its tail.”

The following reference is shocking in terms of the cruelty that humankind has inflicted on animals and I am reluctant to reproduce it, but the completeness-fussy world of lexicography insists it must be included. It is by James Emerson Tennent from Ceylon (1859):

“In the preparation of the mysterious poison, the Cobra-tel, which is regarded with so much horror by the Singhalese, the unfortunate Kabra-goya is forced to take a painfully prominent part . . . The ingredients are extracted from venomous snakes, the Cobra de Capello, the Carawella, and the Tic-polonga, by making an incision in the head and suspending the reptiles over a chattie to collect the poison.

“To this, arsenic and other drugs are added, and the whole is to be ‘boiled in a human skull, with the aid of three Kabragoyas, which are tied on three sides of the fire, with their heads directed towards it, and tormented by whips to make them hiss, so that the fire may blaze. The froth from their lips is then to be added to the boiling mixture, and so soon as an oily scum rises to the surface, the cobra-tel is complete.’”

Constance Gordon-Cumming from Two Happy Years in Ceylon (1892) is the first, but certainly not the last, to mention the ‘saurian show’: “On our homeward journey, as we drove through a cool shady glade, the horses started as a gigantic lizard, or rather iguana, of a greenish-grey colour, with yellow stripes and spots, called by the natives kabaragoya, awoke from its midday sleep and slowly, with the greatest deliberation, walked across the road just in front of us.”

John Still writes, as a hunter, in Jungle Tide (1930): “We put up a kabaragoya, a huge amphibious lizard four or five feet in length, who fled into the nearest covert where the stream ran rapidly through a narrow channel filled with boulders. Kabaragoyas are the creatures whose skins are made into ladies’ shoes. They are flesh-eating animals, very strong, fairly swift, and armed with sharp teeth and a whiplash tail.

“We hunted him just as we were, swimming, wading, plunging deep among the rocks, and following him as hotly as hounds follow an otter. He never attempted to leave the stream, but he led us a chase from pool to rapid and rapid to waterfall, until at last I tailed him as he dived between two boulders. It took the three of us to drag him out, and before his head could whip round and seize one of us we slew him like Goliath with a smooth stone from the bottom of the stream.”

The last and most recent reference is by Michael Ondaatje from Running in the Family (1982): “As children we knew exactly what kabaragoyas were good for. The kabaragoya laid its eggs in the hollows of trees between the months of January and April. As this coincided with the Royal-Thomian cricket match, we would collect them and throw them into the stands full of Royal students. These were great weapons because they left a terrible itch wherever they splashed on skin.”