Recollections of a disappearing world

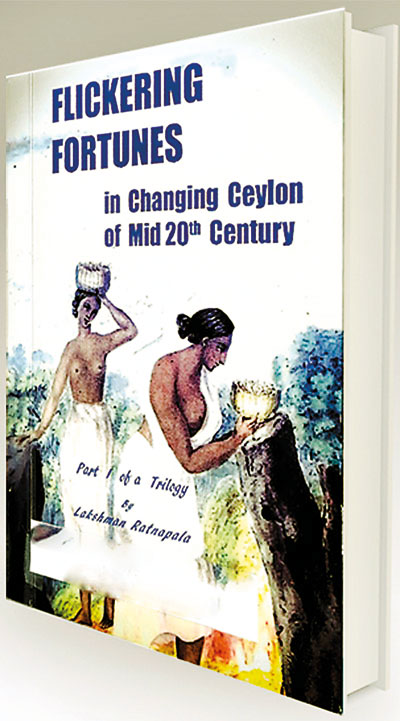

View(s): Despite its opening line, “I am a ladies’ man”, perhaps intended to provoke the curiosity of the lascivious, Lakshman Ratnapala’s Flickering Fortunes, does not consist of the ruminations of a Sri Lankan Casanova now mentally reliving his conquests while residing happily in San Fransisco with his charming wife. In this volume, he traces in delightful prose, episodes of his life, one might say, of privilege, from childhood to his departure from Sri Lanka to the USA. It is an easy and interesting read packed with observations of a world that has almost disappeared. His descriptions of the Sri Lankan village life of his childhood would provide fascinating source material for sociologists and anthropologists.

Despite its opening line, “I am a ladies’ man”, perhaps intended to provoke the curiosity of the lascivious, Lakshman Ratnapala’s Flickering Fortunes, does not consist of the ruminations of a Sri Lankan Casanova now mentally reliving his conquests while residing happily in San Fransisco with his charming wife. In this volume, he traces in delightful prose, episodes of his life, one might say, of privilege, from childhood to his departure from Sri Lanka to the USA. It is an easy and interesting read packed with observations of a world that has almost disappeared. His descriptions of the Sri Lankan village life of his childhood would provide fascinating source material for sociologists and anthropologists.The literary style he adopts is very much a reflection of the education that he received at the private school that he attended in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Undoubtedly, the best school a young boy would want to attend in that magical island. The strongest impression Lakshman Ratnapala’s memories leave is one of a joyful life which has been further enhanced by his marriage to the ‘peach’ that he set forth to pluck on the first day at work with Royal Dutch Shell in Colombo.

Lakshman’s narrative takes us on a slow voyage of recollections from his childhood to his stint as a successful journalist and then to his departure to the USA. The anecdotes he describes, which could have been easily treated as commonplace and quickly forgotten, bring back memories of my own childhood and youth. Many of his Sri Lankan readers, especially those still connected to their original village roots, will readily identify themselves in the stories so cheerily and matter of factly recounted in the pages of this volume.

His descriptions of life in the manor, Malkekuna Walawwa in Kosgama, suggest a Downtown Abbey like quality, only with a rural Lankan character. The interactions of family members, the traditions followed and recounted in Flickering Fortunes without judgement, the unobtrusive insertion of servants, retainers and village folk as players of small roles in the bigger drama, the colourful descriptions of events as they unfolded adding depth and experience to the life of a boy growing up in momentous times, make fascinating reading. Certainly, the ingredients for a television series on a Lankan Downton Abbey are all present in Lakshman Ratnapala’s memoir.

His story contains a valuable socio-economic record of an era that reluctantly dissipated when confronted by the political forces unleashed by independence and democracy. The momentous early transformations that Martin Wickremasinghe documented in his “Gam Peraliya”, Lakshman Ratnapala has described in real time in his life story. An early life of feudal comfort surrounded by doting grandparents and relatives, retainers and servants, private boarding school, sliding in to jobs without much effort on the strength of relationships, family connections and the old school tie, all bring back nostalgic memories of an age that does not exist any more. Or if it does, in a vastly modified form. Ratnapala’s book takes us from an uncomplicated world of feudal privilege to an environment dominated by crass market forces, corruption, nepotism and political opportunism. His commentary guides us through these changes with effortless prose. Through all that, one can not help but note the determination and will of a lad who was always destined to seek something bigger than what his family intended and his little island home provided and about which we are likely to read in detail in the succeeding volumes.

| Book facts: Flickering Fortunes – In Changing Ceylon of Mid 20th Century.Reviewed by Dr. Palitha Kohona |

The wedding of his parents early in the book, described in an unemotional and matter of fact style, records an event which probably reflected the common practices in the country among the land owning feudal class, but which is so rapidly disappearing from the collective memory of the nation as a modern and different environment is embraced. Similarly his description of his birth, the naming of the new born boy, the childhood in Malkekuna Walawwa, Kosgama, its seating arrangements which acknowledged caste distinctions, etc, reflect the customs and experiences of that age. His touching relationship with his grandmother, preparations for Sinhala New Year and the family pilgrimages to Anuradhapura, Nagadeepa and Kataragama are an account of some elements of our society which may still survive in modified form. Going on pilgrimage was the then the equivalent of touring distant places today. Lakshman embellishes his narrative with family lore, drawing on anecdotes of Sinhala history as they related to his ancestors.

Lakshman Ratnapala makes some incisive observations, of a society which was changing under the impact of colonialism and mercantilism which deserve more comment in academic circles. The very caste-conscious environment to which he was born was comfortably accommodated by the colonial administration. Those in positions of privilege easily fraternised with each other despite racial and religious differences. Amidst the ferment, a wealthy indigenous bourgeoisie was gradually gravitating towards a visibly surging Buddhist nationalistic revival, cultural renaissance, and activism for national independence, curiously inspired by an American Civil War veteran, Colonel Henry Olcott and a woman theosophist, Musaeus Higgins.

Ratnapala notes the country’s largely peaceful transitions from colonialism to independence and democracy but describes it, with great perspicacity, as a passing of the baton from foreign “white sahibs” to local elitist English speaking “brown sahibs”. This was a process that was orchestrated as “persuasive cooperation” to avoid bloodshed unlike in India where “Gandhi’s non-violent non-cooperation was anything but non-violent”. The then existing tensions in India continue to generate ethno-religious bloody violence even to this day. Whether Ceylon, Sri Lanka, succeeded with its different approach is another matter.

His commentary on the ascendency of S.W.R.D Bandaranaike and the adoption of his Sinhala only policy is refreshingly sympathetic. Ratnapala explains this, in my view correctly, in terms of a majority excluded from the mainstream of society and the levers of power and privilege by the dominant position enjoyed by an alien language used by a small elite, asserting itself through democratic means. Of course, Bandaranaike, for altruistic or opportunistic reasons exploited this sentiment which was rapidly gathering steam, fed by the steadily expanding literacy and political awareness of the rural masses and the rising tide of Sinhala Buddhist revival.

I distinctly recall my maternal great grandfather admonishing my father for deciding to educate the ‘boy’ at S. Thomas’ College instead of sending him to Ananda! However, contrary to popular sentiment, S. Thomas’, an Anglican missionary establishment originally intended primarily to train the Christian elite, including converts, instilled a strong sense of loyalty to country (note the many Thomians who went to war when the country demanded), public service (three of the first four Prime Ministers, all Buddhists, and many senior and respected public servants, including at least two Foreign Secretaries, were educated there), national awareness (the most ardent exponents of the Hela Havula School of Sinhala were teaching at the school by the sea and front runners in the Sinhala Buddhist revival such as Anagarika Dharmapala received their schooling at STC), and selfless commitment to duty.

Although, inspired by my Hela Havula teachers, I tend to take a different view from Lakshman Ratnapala of the origins of the name Kolamba (Colombo). Kolamba was probably derived from the Sinhala for ‘shallow water’ as opposed to ‘diyamba’ deep water.

Irrespective of a soothsayer’s predictions, Lakshman Ratnapala was destined to swim in a larger pond than Sri Lanka. Circumstances took him overseas, talent and hard work got him to the summit. His rapid rise to the top positions in PATA, eventually becoming President and CEO, his easy contacts with some of the iconic world leaders of the time, his restless travels to distant realms, all suggest that Sri Lanka, a relatively small pond, was meant to lose him. I look forward to reading his follow up volumes.

(The reviewer is former Foreign Secretary of Sri Lanka and Permanent Representative to the United Nations in NY)