Sunday Times 2

Murder isn’t cricket

Swinging high and low, laughing and gulping the salty air blowing in from the sea, two little children were playing in a garden in Bambalapitiya, Colombo 4, one morning 63 years ago, while someone somewhere inside the house was strangling their mother to death.

Prof. Ravindra Fernando, head of the Forensics Department, Medical College, has written two books featuring Mahadeva Sathasivam - one on Sathasivam as a murder suspect, the other on Sathasivam the famous cricketer. Pic: S.P.

The children on the swings were sisters, aged three and four. When the girls had tired of play and gone indoors, they saw their mother’s inert body and thought she was asleep. The odd thing, though, was that Mummy was not in her bed upstairs, where she should have been sleeping, but downstairs, sprawled on the cold cement floor of the garage. She was so deeply asleep and unresponsive, the girls thought Mummy had “fever.”

The two tots would not know till years later that that was the day their lives would be abruptly, brutally and permanently changed. Meanwhile, in the course of that morning, they were being abandoned in stages by the four resident adults in the house, their parents and the two servants. All four adults left the scene at staggered times. At some point, no one knows for sure exactly what time and for how long, the two children were left completely alone on the premises.

The first adult to depart the scene on the morning of 9 October 1951 was the old family retainer Ms. Podihamy, who left the house with the girls’ two older sisters. The Quickshaw cab that called daily to take the two school-going girls and their ayah to St. Bridget’s Convent School had come and gone by 8.15.

The times at which the other three adults “departed” the scene at No. 7, Alban’s Place, Colombo 4 remain unconfirmed to this day. These times would become the subject of intense speculation and debate in the 57-day court trial that followed the murder of Anandan Sathasivam, wife of cricketer Mahadeva Sathasivam, Ceylon’s most popular and admired sportsman at the time.

The other three adults present in the house after Ms. Podihamy left with her charges were Mr. and Mrs. Sathasivam and the servant boy, Hewa Marambage William, a 19-year-old village lad from southern Matara who had joined the Sathasivam household only 11 days before.

Testifying at the Supreme Court trial, Hewa Marambage William said he left the house around 9.30 a.m. that day, after being compelled by his master to assist in the killing of the lady of the house, while the gentleman of the house, Mahadeva Sathasivam, in a statement made earlier in

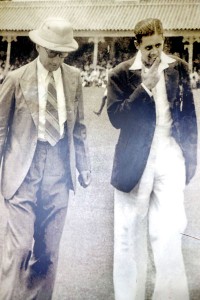

Legendaries: Sri Lankan batsman Mahadeva Sathasivam and Australian cricketer Donald Bradman walk cross the Oval Sports Ground in Colombo in 1948

the Magistrates’ Court, said he left the house at 10.30 a.m.

The time Ms. Sathasivam “left the scene” – in the absolute and final sense – remains undetermined. What is known is that she was alive and reading the Ceylon Daily News before she said bye (forever) to her two older school-going daughters at 8.15.

Marambage William claimed that Mrs. Sathasivam was already dead when he fled the house, never to return, around 9.30. His evidence suggested the murder took place between 9.00 and 9.30. Mr. Sathasivam maintained that Ms. Sathasivam was in good health when he left the house at 10.30. The battle in court was fought largely over whether Anandan Sathasivam was murdered before or after 10.30 that morning.

The Sathasivam case must easily be the country’s most widely covered and intensely and widely discussed homicide. Sixty-three years later, people continue to theorise about what might have taken place in the house that day.

Both the master of the house and the servant boy were charged with murder. Both were missing when the body was discovered that afternoon. The master was arrested that evening and the servant boy 11 days later. Both accused gave plausible accounts of their actions on the morning of the murder. The servant said he was an unwilling participant in the killing, while the master maintained that he heard of his wife’s death only much later in the day, when he was resting at a friend’s home in Horton Place, Colombo 7. After the three-month Magistrate’s Court hearing, the case was passed on to the Supreme Court. The two suspects were held in remand until the trial, which began 18 months later.

In the months leading up to the much-anticipated trial, the case took a dramatic turn when the Attorney-General’s Department made the second accused, the servant, a Crown witness for the prosecution. Servant would incriminate Master in a crime in which he said he, the servant, played only a supporting role.

On June 25, 1953, at the end of the protracted, packed-house trial, Mahadeva Sathasivam was declared “not guilty” and left the court a free man. It was a triumph for Mr. Sathasivam, the blue-eyed boy of Ceylon cricket who had spent nearly two years in confinement, under a black cloud of public suspicion.

Not everyone accepted in their hearts the jurors’ verdict. The public was divided into three camps, those who believed the servant was the killer and had acted on his own; those who believed, despite the verdict, that Mahadeva Sathasivam was guilty, and those who accepted the servant’s story that both master and servant had worked together to get rid of Ms. Sathasivam.

The Sathasivam verdict continues to be weighed by many who have shown interest in the case, studied it, or had personal ties to the Sathasivam couple and the elite Colombo-Tamil families they belonged to.

Our own introduction to the Sathasivam murder came rather early in life, when we were about 11 years old. The celebrated case too was only about 11 years old; in terms of lapsed time, years gone by, the case was not hot or warm, nor was it cold.

One Sunday evening, in the early Sixties, Mother, Younger Brother and self were taking a walk along Galle Road in Bambalapitiya. We turned right into St. Alban’s Place, an unpaved seaside lane of some ten or 12 houses. We were on our way to visit Mother’s uncle, Mr. Joseph Milhuisen, who was boarded at the home of fellow St. Mary’s Church parishioner, Mr. Joe Silva. We were all parishioners of St. Mary’s, Lauries Road.

House No. 7

St. Alban’s Place was unlike most seaside lanes in Colombo. All the houses were on the left side of the lane; on the right was a short wall running down to the railway line, and on the other side of the wall the large Gulam-Hussein property that extended up to Station Road, Bambalapitiya.

A singular feature about the houses down St. Alban’s was that they were all identical. Mother’s running joke with her uncle was that she was never sure which garden to enter. Gates, gardens, houses — all looked confusingly the same. But there was one house Mother would not make a mistake with, and that was No. 7.

As we crunched along the gravel slope, Mother pointed to one house and said that this was the scene of a famous murder. We pricked up our ears. Murder was a recently acquired taste. We were deep into crime and detection, having lately graduated from the adventures of Sherlock Holmes to the mysteries of Agatha Christie and the courtroom dramas of Erle Stanley Gardner. The desk at home was piled high with titles like “The ABC Murders”, “The Body in the Library,” “Three-Act Tragedy”, “The Case of the Runaway Corpse”, and so on. But this was different. Here was real murder, about a real person’s body in a real garage. Moreover, the murder was local, having taken place in the general neighbourhood.

That Sunday evening, as we headed down St. Alban’s Place, the garage doors of No. 7 were wide open and you could see inside. The body was discovered in there, Mother said. Staring into the garage depths, we put our imagination to work. The killing was the work of the servant boy, Mother continued. The boy had even gone so far as to fetch a mirror from a bedroom upstairs to ascertain whether the strangled lady was still breathing. Ingenious, and how very like murder in a book.

Mother was only repeating what everyone knew of the crime from the newspapers and the general talk. She had a vivid way of telling stories, and the details stuck. But it was an open-and-shut case, with the killer identified. The servant boy had done it and that was that. There was no lingering mystery, and we lost interest immediately. Murders in books are more interesting; they offer suspense and mystery up to the last page.

To further dull our appetite for this particular murder plot, there was the triteness of having the servant boy tagged as the guilty party. Servants, guilty or not, have always been the guilty party. That was, and perhaps still is, the rule in feudal society Ceylon. The servant was blamed for anything domestic that went wrong, from missing or broken objects to missing or broken persons, or even murder, should it come to that. How dull. Couldn’t the plot have been better contrived? And there the case lay.

We were regular visitors to St. Alban’s Place in the sixties and, as we recall, the garage doors of No. 7 were always wide open, but the children’s swing in the garden looked abandoned and rusted over.

It would be decades before we learnt about the real mysteries and complexities of the Sathasivam case. The 464-page “A Murder in Ceylon”, published in 2006, has revived interest in the case and introduced the Sathasivam episode to a new generation. The Bambalapitiya murder is a conversation piece of unfailing interest, offering multiple interpretations and possibilities. To heighten interest, the case is studded with familiar and famous names, those of another era.

Justice A. C. Alles’s account was for years the only available text on the Sathasivam case until the arrival of the second book. The Alles outline and summing-up casts a cold, dubious eye on the first suspect, Mahadeva Sathasivam, while Prof. Ravindra Fernando’s book attempts to stay neutral, although some readers find it a tad tilted in Sathasivam’s favour. The author, head of the Forensics Department at the Colombo University Medical College, says his book aims to give the facts and the recorded statements and no more. Readers of the Alles account and Prof. Fernando’s book must decide for themselves.

Prof. Fernando has written two Sathasivam books — one on the Sathasivam at the centre of a famous trial, the other on the Sathasivam hailed as the greatest batsman this country has produced.

Servant boy and Crown witness Marambage William’s telling of how he got entangled in the crime was the framework on which the 1953 trial was hung. Here is his story.

Master said he had a job for the boy

On the morning of October 9, 1951, a little after 9.30, he, Marambage William, was scraping a coconut for the midday meal when the master of the house came into the kitchen, seized him by the hand and dragged him upstairs to the master bedroom. On the way up, the master said he had a job for the boy, and that was to kill his wife. Marambage William refused, saying he would leave the house right away without his 11 days’ pay. The master promised him a reward in money and jewellery and dragged the boy into the room. The lady of the house was sitting on the bed. The master went up to the bed, caught his wife by the throat with one hand, her hair with the other hand, pushed her onto the floor and started to throttle her. He ordered William to grab the lady’s struggling body. When the lady had stopped struggling, the master went downstairs, closed the front door, and returned. He then removed from the dead body pieces of jewellery — a ring, two gold bangles and a thaalikody. He opened the wardrobe, took out a purse and removed money. The jewellery and the money were given to the boy, who was then instructed to help carry the body downstairs. The master held the lady’s upper half, his hands under her armpits, and the servant the lower half. The master leading the way, the two men carried the body downstairs and left it in the garage. William left the house almost immediately, pausing to pick up a shirt and stopping to say a last goodbye to the children playing on the swing.

The prosecution, led by distinguished lawyer and politician Colvin R. de Silva, went to work on Marambage William’s narrative and duly shredded it. Citing the expert opinions of forensic expert Sir Sidney Smith, who had flown out from England to give evidence, and that of Prof. G. S. W. de Saram, they argued that all the evidence pointed to the murder having taken place after 10.30 a.m., the time Mahadeva Sathasivam said he exited the house, leaving his quite-alive wife behind at home. Telephone calls made that morning from the house and pencilled telephone call chits suggested that Ms. Sathasivan was alive and well till long after 10.30 a.m., and possibly up to noon.

Ms. Sathasivam’s body was discovered late that afternoon, around 3.30, by the laundryman. He raised a cry, and a neighbour’s servant came over. A neighbour, Yvonne Foenander, went in to see for herself and called the Bambalapatiya Police, stationed right next door. Just then, the two older daughters and their ayah arrived. A constable arrived five minutes later, and not long after more police, including the Inspector General of Police, Sir Richard Aluvihare. Outside, in the lane, a crowd was gathering.

Mahadeva Sathasivam said he spent the afternoon of 9 October drinking with friends at the Galle Face Hotel, visiting Fort, drinking at the Grand Oriental Hotel, and ending up at a friend’s home in Horton Place, Colombo 7, where he had a siesta. The police arrested him at the house that evening. Marambage William, meanwhile, had taken a bus to Wellawatte, sold the jewellery he was given, bought a change of clothes, had a haircut, visited Panadura, and took another bus later that afternoon to Matara, from where he headed to his village.

The prosecution built a convincing case on the marital disharmony that had for years been troubling the Sathasivam home. The Sathasivams registered their marriage in 1941. Two years into the marriage, Mahadeva Sathasivam was threatening divorce. The couple reconciled, but Mr. Sathasivam’s lifestyle of drinking, gambling, and other forms of spouse irresponsibility, finally drove Anandan Sathasivam herself to seek to end the marriage. There was another woman in the picture, Yvonne Stevenson, a British citizen of Dutch-Polish background. Ms. Stevenson had insisted on a legal split if Mahadeva Sathasivam expected to continue their relationship.

Mahadeva Sathasivam was a trapped man, wedged awkwardly and stiflingly between two women, each determined in her own way. The days and weeks leading up to 9 October 1951 was a fraught time. On the one hand, the mistress was twisting his arm and pushing to break up the marriage; on the other, the legal wife was set on going ahead with the divorce. But divorce was the last thing he wanted; it would mean that the unemployed Sathasivam would have to provide alimony for his wife and financial support for the four children, while maintaining the new woman in his life. Most worrying was how he would continue his life as a dapper, debonair man about town and a popular club personality used to the good things in life.

To be continued next week