Discovering the magic of Gabriel Garcia Marquez

There are books which finish on the last page and then there are books by Marquez. I first encountered Gabriel Garcia Marquez in a library in Delhi. I was in my final year in university and had vaulted through my exams in previous years through an amalgamation of procrastination, last-minute studying and caffeine. During that particular year however, I was a bit more diligent and applied some modicum of method to my madness. We had been eased into Latin American literature just that day and instead of embarking on a reading marathon at the eleventh hour, I wanted to finish the text before we officially started it in class. I headed to the library to begin reading the Marquez novella prescribed for us and when the library closed, I walked back to my apartment and read some more.

Chronicle of a Death Foretold, my initiation into Marquez’s world, persistently remained with me even after I emerged from it that particular evening. Involuntarily I soon found myself rescuing shards of his public personae from books, anecdotes and interviews to form a cohesive picture of this literary supernova whose life was as outsized and fantastical as his writing.

Born on March 6, 1927, Gabriel Garcia Marquez was deeply influenced by his maternal grandparents, both excellent storytellers. From one he heard stories revolving around Colombian history, of the Banana Plantation Massacre, politics and tales of war. From the other, folk tales, family sagas, ghost stories, superstitions and all things supernatural. A shy, reticent boy while in boarding school, he was nicknamed ‘Old Man’ and gradually developed a reputation for having good writing skills. His life was marked by restlessness and having taken up law to fulfil his parents’ wishes, soon abandoned it for writing. At one point, also a (reportedly reluctant) travelling encyclopaedia salesman, Marquez turned to journalism and made a meagre living by writing for newspapers- so meagre that the only rooms he could afford were in a hotel cum brothel.

While he was influenced by his childhood, grandparents and journalism, it was Kafka’s Metamorphosis which was a catalyst in

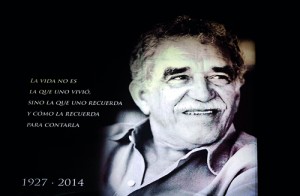

Picture of a banner with an image of late Colombian Literature Nobel Prize laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez and one of his quotes “(What matters in) life is not what happens to you but what you remember and how you remember it,” seen during the tribute paid to him at the Fine Arts Palace in Mexico City on April 21.AFP

Marquez’s writing life and exposed him to a manipulation of language beyond the rational and academic literary examples of secondary school textbooks he had thus far been used to. In Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza’s ‘Fragrance of Guava’, a series of conversations with Marquez, the writer compared this discovery of the potency of literary narration to “tearing off a chastity belt”. In Kafka, Marquez found traces of his grandmother’s pragmatic “brick face” manner of regaling the most atrocious, fantastical stories without turning a hair. The opening line of ‘The Metamorphosis’ i s an excellent example of this technique:“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.”

For Marquez, the point of departure for his fiction was a visual image. The whole of ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’, was triggered by an old memory of his grandfather, taking him to see ice. He has described his characters as being “jigsaw puzzles of many different people and naturally bits of myself”. It was One Hundred Years of Solitude which sealed Marquez’s place in literature and catapulted him to fame and this success weighed heavily on him. In ‘Fragrance of Guava’ he says, “In a continent unprepared for successful writers, the worst thing that can happen to a man with no vocation for literary success is for his books to sell like hot cakes. I loathe being a public spectacle. I loathe television, congresses, conferences, round tables” and compares achieving fame to a mountain climber who nearly kills himself getting to the summit and then tries to climb down, discreetly with as much dignity as possible.

In another interview with The Paris Review, Marquez comments on the solitude of success, of its isolation and its stifling nature: “I would have liked for my books to have been recognized posthumously, at least in capitalist countries, where you turn into a kind of merchandise.” Writes Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza in ‘Fragrance of Guava’, “Not for nothing does the theme of solitude run through his work. Its roots lie deep in his own experience. As a solitary little boy in his grandparents big house… as a penniless student, as a young writer… the spectre of solitude has always haunted him.”Amidst praise for his writing, his friendship with Cuban leader Fidel Castro and resultant blind spot for and implicit endorsement of Castro’s brand of politics drew criticism from the literary and political world.

A proponent of Magical Realism, Marquez’s writing is a mixture of a fermentation of the seemingly fantastical and the realistic and reminds us that “disproportion is a part of our reality” and that “You only need to open the newspapers to see that extraordinary stuff happen to us every day”.

While ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ has been hailed as Marquez’s greatest work, it is ‘Chronicle of a Death Foretold’ which remains a personal favourite. Inspired by an actual event which took place in Sucre, Columbia in 1951, and written 30 years afterwards, Marquez blurs fact, fiction and genre to take us through a very violent, very unnecessary murder. Writing in the first person for the first time, Marquez introduces a narrator who moves freely in the novel’s temporal structure to rescue fragments from the “broken mirror of memory” of a “town that was an open wound”. A blend of journalism and literature, Marquez moves back and forth in time to uncover the moral myopia of a society which allows a murder to take place because machismo takes precedence. “I discovered the vital ingredient – that the two murderers didn’t want to commit the crime and had tried their utmost to get someone to prevent it without success. This is the only real unique element in the drama, the rest is pretty commonplace in Latin America,” explains Marquez in his interview to Mendoza. While explaining that his experience in journalism lent an authenticity to his story telling, Marquez was a firm believer that the best literary formula is always the truth – something novelists tend to forget.

Gabriel García Márquez died at his home in Mexico City, on April 17, 2014 at the age of 87. He is survived by wife, Mercedes Barcha, and sons, Rodrigo and Gonzalo and leaves an astonishing literary legacy which will live on.