A lifetime of research and writing

View(s):This book brings together Professor Senake Bandaranayake’s seminal work on Sri Lankan history and archaeology. It encapsulates the defining ideas, theories, hypotheses and findings of the author’s work during over four decades of thought, analysis and dedicated research. It encompasses the author’s definitive concepts, their theoretical underpinnings and empirical foundations, philosophical perspectives and seminal field research findings published in books and diverse academic journals.

This book of nine chapters provides easy access to the fundamental ideas, theories and hypotheses of his larger works in the field, such as his Sinhalese Monastic Architecture – The Viharas of Anuradhapura (Leiden: E.J.Brill, 1974), Rock and Wall Paintings (Lake House Publishers 1980 and 2010) and the two volumes, The Settlement Archaeology of the Sigiriya-Dambulla Region (1990, 1994).

It is a collection of articles dealing mostly with theoretical issues in the study of Sri Lanka’s historical civilisation. Although the nine essays in this volume have been previously published in a variety of academic and scholarly journals, their publication in a compact volume provides the reader easy access to the author’s lifetime of research and writing and his contours of thinking and perceptions. Bringing them together in a single volume, in the words of the author, “makes for a construct larger than the sum of its component parts.”

The book deals with a range of subjects extending from the agrarian transition of proto historic times to the pre-modern urbanism observable over millennia at several locations throughout the country. One of the influential and definitive contributions of the author is his systematic periodisation of Sri Lanka’s historical trajectory, summarising the work of earlier and contemporary scholars, while presenting his own criteria for establishing distinct developmental and time horizons. Hypotheses on the unity and differentiation of social and cultural formations underpin an attempt to locate the specificity of the Sri Lankan tradition in a matrix of Monsoon Asian cultures.

Bandaranayake categorises Sri Lanka’s historical social formation and puts forward an agenda for studying the patterns and semiotics of power and authority in architectural planning. Critiquing the diffusionist thinking that still dominates South Asian historiography, he directs our attention to the study of the internal dynamics of a historical formation.

Continuities and Transformation is a decisive contribution to the study of historical dynamics from an archaeological perspective. It views Sri Lanka as ‘an island laboratory for studying historical change’. In his Preface, Bandaranayake outlines the evolution of his research interests over four decades, while in the introduction, he discloses the underpinnings of his research approaches and methodology.

The first essay Sri Lanka and Monsoon Asia: hypotheses on the unity and differentiation of cultures, is a departure from the conventional idea of our architecture being an extension of that of the subcontinent. He relates it to a much wider and more complex matrix. As its title suggests, and his argument illustrates, Bandaranayake’s hypothesis is that Sri Lanka’s culture and civilisation is located in South Asia, but it has a Southeast Asian character, which it shares with the wetter regions of Monsoon Asia, extending from Kerala and Sri Lanka, across Southeast Asia, to China, Korea and Japan. The point is made by referring us to the perceptible patterns of similarity and difference in the architectural styles of each sub-region and culture. While the connection with the Indian subcontinent is undeniable, its separateness is a vital differentiation.

His conceptualisation of Sri Lanka in Asia is best captured in his own words:

“Wide open to the sea and continually impacted by external contact in a much-traversed oceanic context, Sri Lanka is also, paradoxically, a closed and internalised territory. In keeping with its terminal location – one might even say its marginality – it displays at various periods of its history its own distinctive mixtures of homogeneity and heterogeneity, and an insular tendency to retain, or to develop to their furthest extent and in highly specialised ways, borrowed cultural traits which were marginal, recessive or abandoned in their place of origin.”

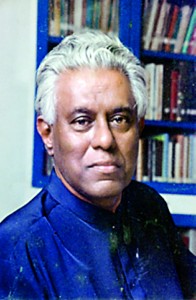

Senake Bandaranayake

This conceptualisation has relevance beyond architecture to understanding the country’s politics and socio- cultural milieu. A related suggestion, with similar implications, in this chapter, is what Bandaranayake calls ‘the Law of the Internal Dynamic’, explaining the distinctiveness of each culture by suggesting alternative pathways of cultural formation, leaving it open to the reader’s judgement

The second essay Feudalism revisited: problems in the characterisation of the historical societies of Asia – the Sri Lankan configuration suggests that there are parallels between Sri Lankan and European feudalism, although there are special features of Sri Lanka’s feudal society, such as checks and balances which regulated the power of the kingly and religious elites, the secular overlords and the peasants and craftsmen. Once again Bandaranayake’s interpretation of social structures is comparative with the wider global historical experience.

In the third chapter Approaches to the external factor in Sri Lanka’s historical formation, Bandaranayake deals with the opposite perspective from the ‘internalist’ views of the first essay, and brings out the complexity of Sri Lanka’s contacts with the world around it. He contends that Sri Lanka is a part of the Indian sub-continent (and the Eurasian landmass) and a nodal point in a vast ocean space. Conse-quently even during the early historical period, Sri Lanka received waves of immigration from various parts of India. During the late historical period, it occupied the crossover point of two circuits of trade and cultural intercourse: those of the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal.

Bandaranayake’s perspectives are broader than the usual historical emphasis on the influence of the subcontinent on Sri Lankan culture. Like in the first essay, he blends the commonality with the Indian subcontinent with a differentiation arising from its similarity with the other Asia.

In the fourth essay Periodisation and some related historical and archaeological problems, Bandaranayake brings together evidence from diverse sources to focus on the unsolved puzzles and theories relating to the great transformations of the first millennium BC.This essay provides a useful framework for understanding the historical evolution of the country in systematic phases of change.

More conventional is his endorsement of the view that the popular Vijaya legend is a literary construction rather than a historical record — a position that all scientific historians accept, though such an interpretation sometimes tends to draw passionate disagreement. Instead the fifth chapter, Settlement patterns of the Protohistoric-Early Historic interface focuses on the relatively rapid transition from Stone Age hunter-gathering to a literate, agrarian civilisation during the first millennium BC. The settlement patterns of the protohistoric times disclose vital insights into the socio economic and cultural transitions of the early historic periods in Sri Lanka. This archaeological research on settlements is one of the significant contributions of the author to the study of history and archaeology.

The sixth chapter Monastery plan and social formation recaptures the author’s seminal concepts expounded in his Oxford D.Phil. thesis Monastic Architecture – The Viharas of Anuradhapura that discusses the social and spatial organisation of Buddhist monasteries during the ancient civilisation. The gist of ideas in that voluminous tome, now condensed in this chapter, is invaluable to the historian and archaeologist.

The next chapter, Premodern urbanism: the morphology of the historical city, reviews the relatively scant literature on the development of urban settlements in Sri Lanka and compares evidence from archaeological research with literary sources. In these two chapters Bandaranayake suggests that we know much more about the evolutions of the monastic foundations of Sri Lanka than about the development of its towns and cities. He urges researchers to focus more effort and resources on understanding the development of urban morphology.

Senake Bandaranayake’s life’s work as an archaeologist has spanned the entire canvas of Sri Lanka’s ancient civilisation, but it is Sigiriya that has been his passion and commitment to discover, explore and create a vision of the palace and fortified city that is the country’s archaeological pride. The eighth chapter, The god-king and the cloud maiden: royal ritual and urban form at Sigiriya discusses Paranavitana’s interpretations of the palace complex at Sigiriya and explores the central mysteries of Sigiriya in a succinct manner summarising and synthesising his vast research output contained in several publications.

The final chapter, Patrons, producers and product: Ananda Coomaraswamy and the study of traditional Sri Lankan art, examines and highlights Ananda Coomaraswamy’s pioneering role in the establishment of a tradition of South Asian art historical studies. This illustrated essay explores the social dimension in the production and consumption of art and ornamentation.

Just as Professor Bandaranayake contributed significantly to the development of a new kind of archaeology in Sri Lanka, Continuities and Transformation introduces new ways of understanding the past. As an economist, one is struck by such ideas as the mirroring and relevance of past historical dynamics to contemporary processes of change; the graphic illustration of irrigation development over the centuries; the (partly conjectured) variation in ‘relative quantities’ in the expansion and contraction of constructional activities in permanent materials as an indicator of patterns of economic growth and regression at different periods of time.

The integration of data, analysis and theory, the formulation of testable hypotheses and the wide ranging focus over a variety of subjects and periods of time, is accompanied by thematic elements running through the book well supporting its title. The cross referencing to the author’s published work and a easy to use index allows the specialised reader to enter a vast field of study with, one might, say, a ‘Braudelian’ scope.

Similarly, the general reader would find it interestingly readable, handling difficult ideas in a smoothly flowing structure, well supported by about 150 illustrations. It is a book which projects the depth and quality of Sri Lanka’s 20th and 21st century intellectual traditions and environment and is bound to influence Sri Lankan historiography over many future generations of interpreters of the past.

| Book facts

Continuities and Transformations: Studies in Sri Lankan Archaeology and History- by Senake Bandaranayake. Reviewed by Nimal Sanderatne |

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus