Sunday Times 2

Mount Everest losing its cloak of ice and snow

Mount Everest is losing its snow and ice at an alarming rate, researchers have found.

A major new study of Everest and the national park that surrounds it concluded the area has been warming since the early 1960s – with many small glaciers having already disappeared.

The researchers said Everest itself was ‘shedding its frozen cloak’ and revealed the snowline on the mountain has risen by 180 metres.

Glaciers in the Mount Everest region have shrunk by 13 percent in the last 50 years and the snowline has shifted upward by 180 meters (590 feet), according to Sudeep Thakuri, who is leading the research as part of his PhD graduate studies at the University of Milan in

|

|

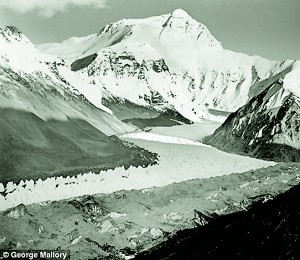

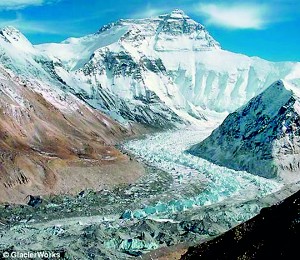

| Then and now: The Main Rongbuk Glacier in the Himayala

region photographed in 1921, left, and in 2009 by the GlacierWorks team. They hope the before and after images, which will eventually be incorporated into the interactive map, will raise awareness of climate change in the area. |

|

Italy.

Glaciers smaller than one square kilometer are disappearing the fastest and have experienced a 43 percent decrease in surface area since the 1960s, the team said.

Because the glaciers are melting faster than they are replenished by ice and snow, they are revealing rocks and debris that were previously hidden deep under the ice.

These debris-covered sections of the glaciers have increased by about 17 percent since the 1960s, according to Thakuri.

The ends of the glaciers have also retreated by an average of 400 meters since 1962, his team found.

The researchers suspect that the decline of snow and ice in the Everest region is from human-generated greenhouse gases altering global climate.

However, they have not yet established a firm connection between the mountains’ changes and climate change, Thakuri admitted.

Sudeep Thakuri and his team determined the extent of glacial change on Everest and the surrounding 1,148 square kilometer (713 square mile) Sagarmatha National Park by compiling satellite imagery and topographic maps and reconstructing the glacial history.

Their statistical analysis shows that the majority of the glaciers in the national park are retreating at an increasing rate, Thakuri said.

To evaluate the temperature and precipitation patterns in the area, Thakuri and his colleagues have been analyzing hydro-meteorological data from the Nepal Climate Observatory stations and Nepal’s Department of Hydrology and Meteorology.

The researchers found that the Everest region has undergone a 0.6 degree Celsius (1.08 degrees Fahrenheit) increase in temperature and 100 millimeter (3.9 inches) decrease in precipitation during the pre-monsoon and winter months since 1992.

Thakuri now plans on exploring the climate-glacier relationship further with the aim of integrating the glaciological, hydrological and climatic data to understand the behavior of the hydrological cycle and future water availability.

‘The Himalayan glaciers and ice caps are considered a water tower for Asia since they store and supply water downstream during the dry season,’ said Thakuri.

‘Downstream populations are dependent on the melt water for agriculture, drinking, and power production.’

A separate team at GlacierWorks has been working with the Royal Geographical Society in London to create a series of ‘before and after’ photographs showing the effect of climate change since 1921.

‘It’s a very interesting time to be looking at the mountain,’ said David Breashears, who led the research.

‘After a while I became interested in climate change, and how it was affecting the area

‘Out of that came the idea for matching photography with Royal Geographical Society to show the first images from Everest with current ones.’

The team now plans to combine the two projects into a vast interactive image of the area so detailed viewers can actually zoom into camps of climbers and see inside tents.

‘We are hoping to launch the next version in June next year, and this is really just a placeholder for what we want to do.

‘You’ll be able to zoom into tents, and swipe pictures to see how the view has changed over time.’

Breashears has spent most of his career working in mountain areas.

‘When I was 23 I wanted to be a mountaineer after seeing the picture from the top of Everest taken by Sir Edmund Hillary.

‘I First went to Himalaya in 1979 to climb Ama Dablam near to Everest, which is over 22,000 feet high.

‘I was also becoming interested in photography, so for the past 33 years have been on 5 Everest ascents, including the first live broadcast, and first IMAX film from Everest.

He also revealed he is currently working with Working Title films on a movie set on Everest, and last year produced a stunning mosaic of images to show the effect of climate change on the the area surrounding Mount Everest.

© Daily Mai, London

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus