Killer wave

View(s):Christopher Ondaatje, author of The Last Colonial reviews Sonali Deraniyagala’s recently released memoir

Sonali Deraniyagala’s horrific book Wave about her experience in and after the December 26, 2004 Tsunami that struck the south-east coast of Sri Lanka is one of the most powerfully moving memoirs ever written.

All year round, day and night, if you looked down that long two-mile line of sea and sand, you would see, unless it was very rough, continually at regular intervals a wave, not very high but unbroken two miles long, lift itself up very slowly, wearily, poise itself for a moment in sudden complete silence, and then fall with a great thud upon the sand.

That moment of complete silence followed by the great thud, the thunder of the wave upon the shore, became part of the rhythm of my life. It was the last thing I heard as I fell asleep at night, the first thing I heard when I woke in the morning – the moment of silence, the heavy thud; the moment of silence, the heavy thud – the rhythm of the sea, the rhythm of Hambantota.

Leonard Woolf Growing

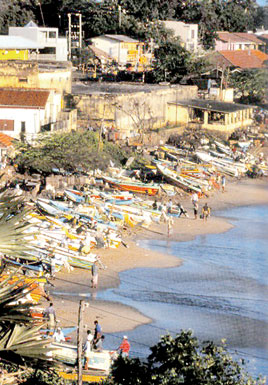

Anyone who has been to Hambantota, stayed at the Rest House, and looked down at the beautiful bay lined with catamarans at the very edge of the town, will remember Leonard Woolf’s description of the sea because it was impossible not to experience what he heard before falling asleep. But it also used to frighten me. It was indeed the rhythm of life on that beautiful bay which has long been known as one of the safest anchorages in the world. The Greek navigators of Alexander the Great knew of the harbour, as did the ancient cartographer Ptolemy, who marked it on his map of Taprobane under the name Dionysii.

Today’s name probably derives from sampan-tota, meaning ‘harbour of the sampans’. Malays, sailing in their sampans westwards across the ocean from Southeast Asia, came to Southeastern Ceylon in search of elephants. Some of them settled here and now, as a result of further Malay immigration, Hambantota has the largest population of Malay Muslims in Sri Lanka. In 2004, they were among the unfortunate people who fell victim to the terrible tsunami which followed the same path across the ocean from Sumatra as their ancestors in their sampans. When the monster wave struck Hambantota on December 26, the bay turned from being a favourite anchorage into a living death trap.

When I was a small boy in Ceylon in the 1940s I always stayed in the Hambantota Rest House with my family, before heading the few miles up the coast, through Tissamaharama, to the Yala National Park which is probably my favourite place in the whole of Sri Lanka. I have been back many, many times, and have written about it in books and articles. In fact I was staying in Yala only a few days before the killer wave struck the south-east coast that Boxing Day morning in 2004. I was researching material for my book Woolf in Ceylon which was published in 2005. Woolf was a junior civil servant in Ceylon from 1904 – 1911 and was Assistant District Commissioner in the Hambantota district, an area which included Yala, during his last few years.

On the morning of December 26, 2004 when this awful thing happened, Sonali Deraniyagala, her parents, her husband and her two young sons were holidaying at the Yala Safari Beach Hotel only a little way from where I had just been staying. Looking out of her hotel window before 9 a.m. that morning, she thought nothing of the unusual sea activity.

A different landscape: The view from the Hambantota Resthouse, taken just six days before the 2004 tsunami

“The ocean looked a little closer to our hotel than usual. That was all. A white foamy wave had climbed all the way up to the rim of the sand where the beach fell abruptly down to the sea. You never saw water on that stretch of sand.”

It was a friend who alerted her. “Oh my God, the sea’s coming in.” At first it didn’t seem that remarkable. Or alarming – only the white curl of a big wave. Then there was more white froth. “The foam turned into waves. Waves leaping over the ridge where the beach ended. This was not normal. The sea never came this far in. Waves not receding or dissolving. Closer now. Brown and grey. Brown or grey. Waves rushing . . . coming closer to our room. All these waves now, charging, churning. Suddenly furious. Suddenly menacing.”

They didn’t speak. Deraniyagala grabbed her children and she and her husband fled. They didn’t stop for her parents or shout to warn them. They ran – down the driveway at the front of the hotel. Ahead of them a jeep was moving fast. It stopped. They ran up to it, hurling themselves into the open back. The jeep driver revved his engine and the jeep jerked forward, driving fast.

“Suddenly all this water inside the jeep . . . Where did this water come from? I didn’t see those waves get to us . . . The water was rising now, filling the jeep. It came up to our chests . . . The jeep turned over. On my side.”

And then pain. That was all she could feel. Something was crushing her chest. She was trapped under the jeep she thought. Flattened by it. The pain unrelenting in her chest. But she was moving. Her body was curled up, and she was spinning fast. Water – smoky and grey – and her chest hurting as if it were being pummelled by a huge stone.

“If this is not a dream I must be dying. It can be nothing else, this terrible pain.” Sonali Deraniyagala’s description of her ordeal is the most gruesome I have ever read. She kept spinning, hurting, bleeding, her clothes ripped from her – almost naked. Floating on her back, water battering her face – the salt going up her nose and burning her brain. There was no sign of her family. Falling through rapids. The water dragged her on and on. Panic. And then suddenly – a branch hanging over the water – still thrashing her face.

“Then I was under it, and I reached out, but the branch was nearly behind me. I threw my arms back a little and grabbed, holding on.”

This is a tragic story. Although she is rescued she soon realises the awful fact that she is the only one in her family still alive. It could only be described as a hell on earth – sitting on the green concrete bench in the Yala Park Museum with a host of bruised and shocked survivors huddled silently on the floor around her before they are herded in crowded vans to a hospital.

How anyone could survive the solitary mental anguish in the following years is something one has to read to believe. Deraniyagala’s Wave holds nothing back. It reveals in its awful truth the black hole of despair and futility. It is six months before she can pluck up enough courage to re-visit the Yala Safari Beach Hotel with her husband’s father and his sister. The hotel had been flattened. There were no walls standing and the surrounding jungle, just like her life, had literally been torn apart.

It is now nine years since the 2004 tsunami and Sonali Deraniyagala, with shocking honesty, has told us the horror that she has lived through. It is obvious that she has struggled hard to tell us not only of this epic tragedy that took nearly a quarter of a million lives but also of her struggle to live with the memory of her lost family. In retrospect the book is also an amazing love story. One can only hope that this courageous openly honest memoir will somehow give the author the peace and release from the nightmare she has had to endure.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus