A reign of fear and great splendour~ From Khiva to Issy-Kul : An Islamic Journey in the Central Asian Heartlands of Timur

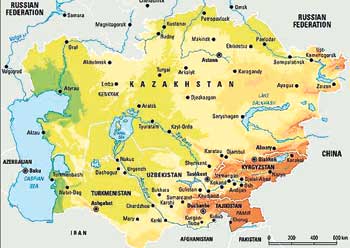

Long, long ago, there lived the greatest conqueror of the world. At his tented deathbed in 1405 AD, on a bitterly cold inky-black February night in the steppes of latter day Kazakhstan, a soul that had singlehandedly caused the greatest misery in human history to date ascended into the night sky. Yet, piled on top of the extreme cruelty, carnage and horrific deaths of, it is estimated, upto 17 million people living from modern day China to Austria, there arose from that very mind - a pound of mere soggy matter - a historical, cultural and artistic legacy that had little or no comparison in the then world, not to speak of military stratagems that caused the Western (and Eastern) worlds to quake with fear. There arose sophistication and diplomacy conducted in nomadic tents that had outfoxed ruler upon ruler, toppling and binding khanates into revolving hybrid units of alliances, and, ironically, still leading to a remarkable (at least fear-reinforced) unity across half of the known world, a world larger than that of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC). The material splendours that it formed left the Taj Mahal (1650 AD) in its aftermath; the cradle of scholarship that it spurned reached out to the stars before Copernicus. That such an extreme divergence of achievements could emanate from a physically lame albeit Machiavellian ruler over such a vast space on this earth - larger than that enclosed by most modern national boundaries and covering spheres of political influence daunting even in today’s technologically driven world - was as compelling a reason as any to lure me, one Spring day in 1999, to the mystical lands of Central Asia. The intertwined influence of his empire on the Silk Road was another (fired by an extraordinary exhibition of Timurid art witnessed at the Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian in Washington DC in 1988); for it was his munificence that fuelled the pinnacles of artistic and trading activities (earlier sustained by the great Sogdian and Bactrian civilizations), the lifeblood that coursed, and some would say cursed, through the many veins of the Central Asian Silk Roads, the vital human link between the then East and West. Centuries later, today, we are only at the tip of the genetic superhighway that this Road spun in its wake and such discoveries may well supersede the conventional and myopic definitions of nationality and border control that sustain today’s politicians. The Early Life of Timur, “Scourge of the World” This then, most briefly, is the legacy of Timur (“iron”), or Tamerlane (an English corruption of Persian Timur-i-Leng to Timur the Lame), the ruler whose humble origins were all too misleading. Born in 1336 AD at the Uzbek town of Kesh to a minor noble of a Tartar derived clan (-Turkic descendents of the Mongol Genghis Khan (1167-1227 AD)), Timur’s ambitious nature and his fighting skills slowly found their way through the rough cut-and-thrust of steppe alliances. By 24, he had claimed leadership of his tribe and thereon increasingly ambitious friendships and rising military skills were forged. Around 1363, aged 27, Timur received a debilitating injury to both right hand and leg which earned his epithet “Timur the Lame”, though lame in action he was not to be. This did not thwart his emerging personal struggle to liberate Shakhrisabz, the heartland of Mawarannahr (Arabic for “that which is beyond the river”) - today the“-stans” of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Xinjiang (Chinese Turkestan) which encompass more than 7 million square kilometres. This vast area was also known in Latin as Transoxiana (“beyond the Oxus River” and serenaded in Byron’s Road to Oxiana), sandwiched between Central Asia’s two greatest and life giving river systems, Amu Darya (in Greek, the Oxus, flowing 2400 km from the Pamirs to the Aral Sea) and Syr Darya (in Greek, the Jaxartes, flowing 2200 km from Tien Shan or Celestial Mountains to the fast disappearing Aral Sea). Timur’s rallying quest was to seek liberation from the Moghuls whose home base lay between Lake Issy-Kul (central Kyrgyzstan) to the Tarim Basin (central Xinjiang). And this he did, with the result that in Shakhrisabz, “the Green City”, he was to raise one of his many fine palaces, Ak Sarai, amongst countless other Timurid monuments that dotted and defined his subsequent vast empire. “Let he who doubts our power and munificence look upon our buildings” was his utterance, and though I did not know this statement then, it was precisely those extraordinary words and buildings that drew me, personally, to his lands 600 years later. A frabgious spring in Tashkent In Spring 1999, shortly after an unusual series of car bombs exploded in otherwise peaceful Tashkent, and unwilling to change my plans, I flew nervously into this pleasant but dilapidated capital of Uzbekistan. I was accompanied by a companion, Tilak Hettige, a respected photographer interested then in a photoshoot of a school for a development publication. Through him, and generously assisted by his well placed friend in an international organization in Tashkent, we gained our difficult entry visas after biding time in New Delhi and becoming “Consultants”; Uzbekistan then was not tourist-friendly. Even the midnight flight was eventful, with overzealous Uzbek airline staff attempting (successfully, through trickery) to charge us for slightly overweight rucksacks, while large Uzbek peasant-trader ladies with wodges of banknotes in hand and worryingly even larger “hand-luggages” (haystack proportions of bagged Indian goods for sale back home) jostled for seats. In the midst of a lengthy inexplicable delay at midnight on the Delhi tarmac, we were then treated to the full fury of one very angry Uzbek man whose powerful yelling down the aisle at the delay withered the crew into helplessness, brought the captain down pronto and caused clearly submissive entreaties from the pilot. To the applause of the entire aircraft, the passenger got the plane airborne. It was, for me, a whole new way of registering an onboard customer complaint, and one not likely to be seen in the West or East. Whether we could be airborne for long was a seriously vexing question as ladies’ payload safety did not seem a big issue on the Soviet built Ilyushin aircraft. Presumably the planes were as tough as their pilots.

I took an unexpected and immediate liking to Soviet built Tashkent. It is, in fact, an ancient and earthquake-prone trading settlement dating back almost 2000 years (last almost obliterated in 1966) but today it filled me with a strangely nostalgic feeling of an old and orderly Vienna of the 19th century (even stranger when one considers its nearness to chaotic India). How coincidental then is this description by an Austrian prisoner in 1916/21 written to Ella Christie in Through Khiva to Golden Samarkand (1925). “When I arrived in Tashkent it was a garden city of striking beauty, with modern shops, carriages, motor-cars, with the life of a small European capital. What has the October revolution made of Tashkent? Today it is a dead and filthy town, where nothing remains to remind us of her pristine beauty.” Long broad tree-lined roads, with distinctive adjacent Spring-fresh forest corridors which I admired, some interesting buildings though not ones of great classical beauty, and limited Lada and locally assembled Daewoo-cars gave Tashkent a pleasant laid-bck atmosphere; it also featured Central Asia’s only underground metro system. An old Soviet styled department store near me had limited goods on its shelves – as did my favourite modern Turkish fast food cafe which opened and closed on different days as it perplexingly and probably ran out of food (finding reliable meals was a preoccupation). But it was my perambulations through some of the city’s traditional markets that simply left one’s head reeling. In the heart of Silk Road bazaars Nowhere in the world, not even in Kashgar or Istanbul, was I to encounter such gigantic produce-filled marketplaces as in Chorsu and elsewhere in the city, where exasperated farmers from what was the Soviet Union’s former bread-basket sat and waited in orderly fashion to sell a few goods. Buyers were few then and the collapse of Moscow’s guaranteed urban demand and effective transport linkages had thrown Uzbekistan’s rural producers into despair while the once fertile (and heavily fertilized) endless fields slowly ran out of all inputs and thereby productivity – as I was to witness on my travels. Often more than half a kilometre long and with large covered domes, the city markets were divided in produce zones; fruits (delicious apricots, cherries, peaches, mandarins, mulberries, lemons to name a few), vegetables (assorted), breads (of all forms, a key food in Central Asia) and nuts (almonds, walnuts, hazelnuts, peanuts, raisins etc.) were bountiful; a typical seller had visually challenging sacks of graded almonds in gunny sacks each of at least 300-500kg. Despite the police and security men present everywhere, in the marketplace as in the countryside people exuded friendliness and warmth in a very Turkic fashion and the notion of what the Silk Road’s banter and ambience would have been like could be easily gauged in this colourful atmosphere. I was routinely cornered, agreeably distracted and fed, often free of charge, and many smiles and failed communication efforts expended most happily. The only difficulty, I recall, was crossing the “meat zone”. Neatly ordered and displayed limbs and innards of goats, cows and sheep - like costume jewellery - lined the rows of stalls, and the smell - though the areas were very clean and neat - was novel enough to make me retch uncontrollably and be unable to photograph, let alone be courteous to the beckoning sellers. A city of some hidden “charms” Out of Tashkent’s historic markets and associated mosques (-one of which, the Tilla Sheikh, is home to the world’s oldest Holy Koran, written in 646 AD and returned from St. Petersburg by Lenin, no less, to Muslims in Uzbekistan), the air of a recently crumbling Soviet republic uncertain of its own future pervaded normal life. My hotel which was situated pleasantly overlooking Tashkent’s well known and traditionally elegant Navoi Opera and Ballet Theatre building (where I later enjoyed “Giselle”) was more of a garrison; an old building which was multi-storied and multi-winged like many here, though I suspected many corridors were defunct and in disrepair. Indeed, our shared room and its contents, simple, rickety and well aged with dim yellow lighting, distinctly exhibited a rather charming old American Wild West cowboy bedroom, although its narrow wrought iron balcony ledge gave me an excellent vantage into the refreshing tree-filled boulevard below me.

Gazing at my new surroundings - such a far cry from Delhi - the evening was especially memorable; I drew in the cool dry climate of Tashkent (winters are temperate here) and spaciousness of an orderly Russian city without neon lights or the usual modern facades. Even more, as I idly looked down bracing on my railing, was the scene of a young couple walking past the old cast iron lamp-lit boulevard. A strikingly tall and elegant Tashkent girl of fair Anglo-Chinese features with simply acres of legs and a short miniskirt (as seemed to be the dress code) sauntered past with her beau, giggling and chatting, while several others with surprisingly equal looks followed by. Some town! It was then that the full meaning of a chance conversation some months prior with a Pakistani diplomat in Manila, formerly posted to Tashkent, took form. Anxious then to find out more about travel conditions in this little known ex-Soviet country, I had requested his advice. The man, noting two young men travelling alone, visibly regressed into cold sweat while regaling us – with considerable expression - not with factual logistical details of travelling in Uzbekistan but with the beauty (-how true!) and liberality of the women of Tashkent. His seemingly tall tales of toplessness in city fountains in summer seemed rather far fetched to me, this in a notionally Islamic state where the Ferghana Valley to the north-east housed centuries-old orthodox Islamic communities. Indeed it took some convincing to educate him of the “other” wonders of the Silk Road and we left him subsequently very despondent at being transferred to Manila while our own incredulousness and uncertainty (tinged, I might add, with a certain entertaining fascination) was notably higher. Of dollars and foregone massages Whatever religiously ominous considerations I might have had began to slowly evaporate in our Tashkent hotel itself. Each wing of this building was populated with a floor level minder: at the end of each hotel corridor, mostly elderly Russian ladies armed with their thermo flasks, hotplates, radio and knitting needles made night vigils on behalf of their corridor guests, such as there were. Any query was handled by them, though not in English but with great charisma and long bouts of Russian monologues that sometimes left one feeling somewhat wind-blasted. The service proved double-edged for Uzbekistan was allegedly a notoriously informant state then; the police were omnipresent (as was a large mafia) and personal documentation was de-rigueur (imprisonment for lack of papers was not uncommon). Furthermore, as “Two Single Men”, a privilege beyond measure in the glazed eyes of our Pakistani friend and now a vital statistic immediately relayed by the hotel staffs to prospective “ladies of the night” - we were sitting ducks; innumerable late night phone calls for “massages” were a notable feature of most urban nights across the country until in exhaustion - after answering - the phone was put off the hook. The attention was flattering, though it may have had more to do with what was in the pocket rather than in the trousers: foreign currency! With a nearly threefold discrepancy then between the official exchange rate for dollars and blackmarket rate, money changing was also a high priority activity for the ladies – in fact money changing and nocturnal visits went rather well together (though the service units of exchange portrayed very saddening personal stories). It illustrated the rampant daily inflation that obsessed day to day city life at that time and both plagued and confused societies across the former rigidly controlled Soviet Union. Shortly before planning a long trip out of Tashkent, I decided to convert my dollars. Having done so in my hotel room at some risk, I then fell into a serious and unanticipated quandary: my $720 now fetched a staggering 322,000 Soum – and there were no 1000 Soum denominated notes! Counting it all was tedious and fraught with the worry of a knock on the door; moreover I was forced to buy an entirely separate rucksack purely to stash the cash and this placed us both in a dangerous position for rough long distance travel punctuated with countless police checks en route. (Had it been today, I would have been confronted with an astronomical 1,267,900 Soum [4 rucksacks] and that is only the official rate!) All for the sake of a genuine Bukhara carpet. With good reason, my travelling friend worried about my sanity. Next Week : To glorious Samarkand, the heart of Timur’s Empire. |

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Reproduction of articles permitted when used without any alterations to contents and the source. |

© Copyright

2007 | Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. All Rights Reserved. |

Across fabled Samarkand to Khiva and then beyond to Lake Issy-Kul deep in Kyrgyzstan and the steppes of southern Kazakhstan, Nishy Wijewardane journeyed in 1999 through the heart of Timur-i-Leng’s Empire (today’s Uzbekistan), uncovering the extraordinary legacy of the world’s most feared ruler to date.

Across fabled Samarkand to Khiva and then beyond to Lake Issy-Kul deep in Kyrgyzstan and the steppes of southern Kazakhstan, Nishy Wijewardane journeyed in 1999 through the heart of Timur-i-Leng’s Empire (today’s Uzbekistan), uncovering the extraordinary legacy of the world’s most feared ruler to date.