|

Special Reprot21st February 1999 A dream comes true |

Front Page | |

|

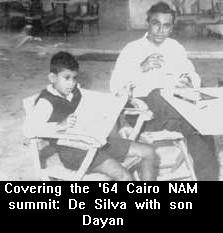

“Mervyn de Silva, a senior print and broadcast journalist,

turns 70 later this year. In this unusual and intentionally premature evaluation,

his son Dayan Jayatilleka suggests why the media community should be preparing

to felicitate him” Continued from last week Column and feature ar ticle, short review and editorial, news lead and interview- De Silva did it all. He also was it all- free lancer, reporter, deputy editor, editor, editor-in- chief, print journalist, radio and briefly television commentator, mainstream mediaman and alternative periodical editor. Through the welter of roles and simultaneity of functions however, there is a discernible non-linear progression, an uneven evolution of sensibility, style and subject matter. The reading, reference points, and subjects for literary critical comment changed, with de Silva moving to British espionage fiction ( introducing Le Carre to the Lankan newspaper reader) and simultaneously along the tracks laid by the modern American Romantics to the next stage of their evolution: Chandler, the private eye novel. Also cinema, that quintessentially American art form. This would seem the embrace of the low-brow and the ‘ philistine’ to one who has not come upon Sartre’s revelation that French Existentialism was inspired by the American private eye novel! De Silva had gravitated then, to genres more reflective of contemporary reality, of contemporary urban civilisation, in their faster pace and the nuanced ambiguity of the moral choices made by their tarnished heroes. Scott Fitzgerald had already exposed the hypocrisy of upper-class America - and who was Chandler’s Marlowe but Nick Carraway with a gun, collar turned up in Hemingway’s eternal rain? Mervyn de Silva, thought to have been the most naturally gifted student and stylist to enter the English Dept, had been led by the selfsame gifts to the realisation that John D. Macdonald’s Travis Mcgee , Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer and John Le Carre’s George Smiley (and Alec Leamas) had more authentic, usable insights to offer into the bleaker inequities of the contemporary human condition, than most in the Great Tradition. He would return if provoked though to that old turf, as in the brilliant polemic on Ezra Pound with Reggie Siriwardane, while editor of the Daily News. His defence of the relevance and contribution of the poet entitled ‘A Penny for Old Pound’ against his teacher’s facile, politically correct judgement (“he supported the fascists”) was validated after the Nicaraguan Revolution when its foremost bard, Ernesto Cardenal acknowledged his debt to Pound. The more fundamental evolution though was in subject area: from literature and ‘literature and politics’ (Malraux) to politics itself. Critiquing Feurbach’s critique of religion, Marx argued for a progression “from the criticism of theology to the criticism of politics”. Detecting that the kind of dramatic conflict and unfolding of human passion which was the stuff of good literature was most closely approximated in real life precisely in the theatre of politics, Mervyn occupied a front row seat, turning from the criticism of literature to the criticism of politics. Lake House And Politics Until its homogenisation in opportunism and mediocrity under the present regime, Lake House was, for decades, crosscut by contradictions - UNP vs. ‘Left’, Western vs. Eastern, English vs. Sinhala. In 1978 Ranil Wickremesinghe and Anura Bandaranike were to hurl at each other the self same epithet from either side of the Parliamentary divide, about Mervyn, then the editor of the newly founded Lanka Guardian: “he was your father’s blue eyed boy”. Esmond was his first mentor at Lake House but Esmond’s project was ultimately party-political. To de Silva the UNP represented the status quo - and the Lake House UNPers actually were in that Cold War context, pro-American. To their credit, Denzil and Tarzie, once they liberated themselves from Lankan political polarisations, went on to make significant progressive contributions to the Third World cause. Esmond sensed that Mervyn’s ultimate loyalty would never be to any party-political cause and quickly installed the less talented but ideologically ‘sound’ team player, Ernest Corea in the vacant slot of Daily News editor which de Silva was a natural (and the seniormost) choice to fill. The Lake House ‘Left’ on the other hand, was fanatical when it was not furtive. It is observing their subculture that Tarzie coined some of his favourite aphorisms: ‘This is one country where there can be smoke without a fire, and every man with five bucks more in his pocket than you is a CIA agent’ - and his laconic Lankanisation of Othello : “he who steals my purse I’ll thrash!”. ‘Andaya’ was a pet aversion for them - an almost wholly westernised man (Tarzie would deploy his Anandian roots and ritual return to his village for shrewd tactical effect) who not only doubted the metallurgical exactitude of the appellation ‘Golden brains’ but effectively lampooned the pompously petulant leaders of the LSSP. Thus de Silva in late 1964, was wrongly suspected by his bosses of having conspired with Sirima and Felix Bandaranaike in Cairo - while covering the NAM summit - to nationalise Lake House. And de Silva in 1976 in yet another aftermath of yet another NAM summit, this time in Colombo, was sacked from Lake House by Sirima Bandaranaike. Thus also his only offspring’s experience of denunciation as “the son of a Communist” at school and “the son of the CIA agent” on and off campus! By the April insurrection all his gambles had paid off: he was the editor of the Daily News, a boyhood dream. He was no longer on the outside looking in. And yet when that insurrection exploded he published a long, sensitive, sympathetic yet objective piece in the op-ed page of the Washington Post commencing characteristically with Eliot : ‘April was the cruellest month…’ In 1978 after the JVP’s legalisation the party took an exhibition on the road which I viewed at Peradeniya having crossed swords with Wijeweera at the New Arts Theatre. It had a painstaking reconstruction of ‘How the bourgeois mass media helped prepare the repression’. Conspicuously absent were exhibits from the papers edited by de Silva at Lake House. In fact the Daily News had given Wijeweera’s press conference in early ’71 very fair coverage and had editorially engaged with him in a spirit that was curious yet constructive. In 1973, one step up the ladder and reaching the pinnacle of his career, that of editor-in-chief, de Silva would be criticised in cabinet by Colvin R. de Silva for his paper’s “curiously scrupulous balance” in its coverage of Dudley Senanayake’s funeral. A long essay (‘Sri Lanka: The End of Welfare Politics’) that same year in the South Asian Review ,the journal of the Royal Society for India, Pakistan and Ceylon, provided a frankly critical evaluation of the prevailing crisis and its roots. Professional values Compulsive fibber though he was in everyday life, when de Silva sat at a typewriter he was intellectually honest as few could be. His ultimate loyalty to the right word in the right place outstripped his loyalty to his political patrons. Sirima Bandaranaike resolved the contradiction for him demoting him from editor Daily News (‘70), editor in chief and Director (‘73), to editor Sunday Observer (’75) then to senior editorial advisor and finally out the door. (A year later she would follow suit at the hands of the electors). Hired by his old school chum Haris Hulugalle as editor in chief of the Times Group, he was the only holder of that designation in two major and rival newspaper combines. In ’78 he was fired from the Times at the instigation of the new UNP government after he editorially criticised its first budget. When Lake House Provincial correspondents on their annual pilgrimage to the citadel, brought huge baskets of local produce for the new editor- as was their custom - he sent them all back. And when the huge multinational Pfizer used an American friend to influence him against running an expose in the Lanka Guardian, Mervyn ran the story, went on the BBC and blew the whistle! He could be dazzled, fooled, influenced at the margins, seduced and slightly corrupted- but never bought up. A countervailing factor to temptation was a pronounced intellectual disdain and a stated feeling that businessmen , the military, cops and resident whites should be kept in their place. This was his town; the feeling shared by that self-confident generation which emerged from Peradeniya into a comfortably affluent newly independent Ceylon like a cork popping from a bottle of Dom Perignon ’53. (It was a good year.) Over the years Mervyn’s bosses and rivals in both political camps had used the word ‘unreliable’. The dual sackings proved that this was a synonym for ‘independent’ or much more accurately, ‘non aligned’. As he went into a downward career spiral he had only one strident public defender - a long time friend and the (Peradeniya educated) prince of Sinhala journalists, B.A. Siriwardena. In one of two blistering Aththa editorials attacking the SLFP government for the dismissal, Siriwardena commenced with a deft flick of the wrist: “It is a widely held view that Mervyn de Silva writes English quite as well as we write Sinhala…” Sira had it right yet again. The two greats would meet often at Simeon’s joint, the lower depths of the Lankan journalistic world, the Press Club and while he and my father drank and ate devilled beef, Sira would regale me with what it was like in the good old days of Papa Joe Stalin: Come the next non aligned summit, this time in Havana in 1979, Mervyn was free and clear. The labour courts had awarded him the highest sum granted until that time for unlawful dismissal, which combined with his provident fund enabled him to launch the Lanka Guardian. He had turned fifty having been invited by the Cubans to watch Fidel taking the rostrum and the Chairmanship. De Silva had always been an aficionado, but never a practitioner, of the critical ‘little magazine’. Among the things for me to look forward to at home was the flow of the periodicals. Partisan Review, Encounter, Problems of Communism, Survey (edited by the encyclopaedic Leo Labedz who befriended Mervyn) Monthly Review, National Review, Ramparts, New Statesman, the Foreign Affairs Quarterly, Foreign Policy and most prized of all, the New York Review of Books. (Mailer’s review in it of Brando’s explorations in the Last Tango in Paris made for one of the racier conversations I’ve heard - between Mervyn and Tissa Wijeratne in Paris). But the Lanka Guardian would turn out in its decade long hey day, to be more a New Statesman-cum- Spectator than any of the others. Mervyn’s proper province remained ‘Men and Matters’ and not ‘Ideas and Ideologies’- the discussion of which propelled those more serious journals. If Walter Lippman and Scotty Reston were his heroes while editor in the mainstream, it was I.F. Stone when he stepped out of it. Intellectual though he was (his arc of literary achievement had work of much better quality than almost any Lankan academic) he was incapable of the intellectual (and ideological) guidance that Philip Rahv, Elizabeth Hardwick, Stephen Spender, William Buckley Jr. or Paul Sweezy could and did bring to their publications. Interestingly though, Mervyn had showed himself the editorial enabler par excellence of intellectual discussion not only in his editorship of the Lanka Guardian but earlier as the editor of the Sunday Observer in his period of demotion. That was perhaps the most stimulating of his editorial years at Lake House: actually raising the circulation of the paper by publishing long, multi part think pieces (e.g. Senaka Bandaranaike on the Peoplisation of Lanka) and exciting cultural debate (Sarath Amunugama; a split page pictorially illustrated exchange between Reggie, Manik and Lester on Kalu Diya Dahara). Intellectual impresario and umpire then, not intervener. Whether the final format and destiny of the Lanka Guardian will be as a serious critical-intellectual quarterly practising the ‘higher journalism’ (Denys Thomson in Scrutiny), whether such is sustainable in Sri Lanka and indeed in the post-modern world order, or whether the LG will be laid gently to rest with its founder-editor are , hopefully, dilemmas which will not disturb us until well into the next century. But they are ineluctable. -Part III next week

|

||

|

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to |

|