![]()

When

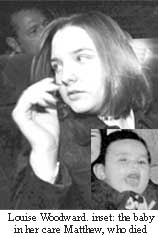

Woodward, chubby, popular teenager, passed four A-levels, she decided like

many others, to travel rather than immediately take up the university place

she had been offered. In June last year, eager to broaden her experience,

she headed for America and through an agency called EF Au Pair, found herself

with a family 30 miles north of Boston.

When

Woodward, chubby, popular teenager, passed four A-levels, she decided like

many others, to travel rather than immediately take up the university place

she had been offered. In June last year, eager to broaden her experience,

she headed for America and through an agency called EF Au Pair, found herself

with a family 30 miles north of Boston.

By November the family had let her go because they did not agree with the hours she kept. The family found her a job with Sunil and Deborah Eappen, who also lived near Boston. The Eappens both worked full-time, and paid Woodward about £75 a week to look after their two children, Brendan, a toddler, and Matthew, the baby. Initially they wanted her to agree to be home by 11 pm each night, but when Woodward demurred they agreed to a month's trial without a curfew.

Both Woodward and the Eappens later acknowledged that this arrangement did not work. Woodward was fascinated by the youth musical Rent, which was playing in Boston, and went to see it at least 20 times. She found it difficult to keep to the curfew and often came back in the early hours. On occasions she slept in and was not ready to look after the children when Deborah Eappen went to work.

On January 30 the Eappens gave Woodward an ultimatum, a written list of conditions telling her what they expected her to do, or she would be fired. According to the prosecution, Woodward was annoyed by these conditions and confided to an acquaintance that the Eappens were "demanding", that their children were "spoilt" and that Matthew was a "brat".

Four days after this incident the police got an emergency call from a frantic Woodward. According to her testimony last week, she had found Matthew, who had been crying most of the day, gasping in his crib. "He was lying there and his eyes were half-closed", she said. "He was gasping for breath. He was kind of off-colour." She tried to rouse him, she said.

"I was clapping, and when he wouldn't respond I lifted him up and shook him," she said. 'He was unresponsive. I was really frightened. I panicked." She denied that she had ever shaken the baby violently, slammed him or done anything else to harm him.

The prosecution produced a string of expert medical witnesses to back up claims that Matthew died of severe head trauma as a result of so-called "shaken baby impact syndrome".

"This shaking was to such a violent degree that it would have required as much energy as an adult could muster, sustained over a period of time up to or exceeding a minute, possibly delivered in intervals," said Eli Newberger, a paediatrician who examined Matthew at the hospital. "My opinion is that all of the injuries are attributable to child abuse."

The defence, galvanised by the attack-dog tactics of Barry Scheck, who worked on the O.J. Simpson murder case, managed to cast considerable doubt on significant parts of the prosecution case. It sought to highlight disagreements among prosecution witnesses about how the injuries to the baby might have been caused, and suggested that Matthew might have suffered an injury as much as three weeks before, which nobody spotted. Defence lawyers hinted, though did not specifically suggest, that this injury could have been caused by Brendan, Matthew's 'boisterous' two year-old brother.

In one exchange the defence forced Dr. Mandi, the doctor who had treated Matthew in the emergency room, to admit that he had found no evidence that the baby had been shaken, saw no bruises on the baby's arms, shoulders, ribs or neck, and no swelling on the back of the baby's head which would have been consistent with it having been slammed into a hard object.

Expert witnesses backed the defence's forensic argument. Probably the most effective was Dr. Lawrence Thibault, considered to be the country's leading expert on "shaken baby syndrome".

"Matthew Eappen did not suffer a violent impact to the head and certainly not on February 4," Thibault told the court. He said that if the baby had suffered the kind of injuries one prosecution witness had suggested, his head would have smashed.

Think of dropping an egg, he said, The shell not only cracks but it will penetrate, move inward toward the yoke as the skull would move inward toward the brain." As the jury weighed the medical evidence, Woodward electrified the court by giving testimony. She admitted she had panicked when she realised that there was something wrong with the baby, but strenuously denied that she had harmed him.

But the prosecution pointed out that according to the police, Woodward had told them that she was frustrated that the baby had been crying all day, and that she had "tossed the baby on the head" "dropped the baby on the floor" and "may have been a little rough". What exactly did those words mean?

The case raises awkward questions about how families, in an age when many women need to work, arrange childcare. This is not the first tragedy of its kind. EF Au Pair, which is funding Woodward's defence, is currently being sued for $100m by the parents of another baby that died while in the care of an au pair the firm had supplied.

In 1991 Olivia Riner, a 20- year-old from Switzerland, was placed with Bill and Denise Fischer in Westchester, New York, to look after their three-month-old daughter Kirstie. A month after she joined the family Riner called the emergency services. They arrived to find the house engulfed by three separate, deliberate fires. Later they discovered that flammable liquid had been poured over the baby's body.

The day after the fire Riner was charged with arson and second-degree murder. Just as in the Woodward case, the agency paid for the defence attorney on Riner's behalf.

She was acquitted and returned to Switzerland something of a heroine. Television footage showed her being driven through the courts in a fire truck. At the time of the trial nobody in America had known that Riner was the daughter of a fireman.

When uncertainties emerged over the references Riner had supplied, the Fischers decided to sue the agency. The $100m lawsuit filed against EF Au Pair claims that despite the agency's advertised claim of a rigorous screening process, it did not properly check Riner's references and sent them an au pair who was unqualified and unsuitable. The agency is fighting the suit.

At stake is a business that has become remarkably lucrative in the past decade. Demand for au pairs in the United States is enormous, particularly for British women, who are often seen as a status symbol. Families pay an agency a fee of up to $4,000 for each au pair. The au pairs receive a return air fare, less than £100 a week, full room and board, and are expected to stay with the family for a year.

In return, however, they are asked to work long hours at a job for which they may have few formal qualifications. Often they are in effect full-time nannies.

"In America people don't understand the difference between an au pair and a qualified nanny" said Mike McKintosh, secretary of the British-based Au Pair Association, a non-profit organisation which supplies au pairs to Europe. "An au pair is not meant to be cheap domestic labour but a member of the family who does some part-time work. Unfortunately, there are plenty of agencies which are prepared to supply au pairs to parents of babies. The parents want full-time help and the au pairs don't know what they're letting themselves in for."

Traditionally, the au pair system developed as a method of cultural exchange, giving young people the opportunity to study other languages and people. The hours of work were strictly limited and in some European countries still are under a Council of Europe convention dating from 1968.

Gaby Morris, co-owner of the Riverside Nannies agency in London said: "The au pair system can work very well in families with school-age children or in families where the au pair is a back-up to a nanny. But it doesn't work when parents are looking for cheap full-time childcare and see the au pair as a substitute for a trained nanny. In Britain the boundaries are also stretched to the detriment of both sides: parents feel let down, au pairs feel exploited. But for many working parents there is no easy answer. A properly trained nanny can cost £250 a week, plus tax and insurance.

But cases like that of Woodward are forcing authorities to address the shortcomings of the current system. The United States Information Agency, which oversees the au pair programme under which about 10,000 foreign au pairs a year are allowed into America, is tightening regulations.

From now on the eight agencies that are allowed to bring au pairs into the country will have to ensure that those who look after children under two years old have had at least 200 documented hours of childcare experience. Au pairs will also be limited to working no more than 10 hours a day or 45 hours a week.

As the Woodward says the wider audience may well reflect on one simple point. When the teenager arrived in America to embark on the difficult, precious task of caring for a baby and a two-year-old, her training in childcare consisted of only a four-day course.

– The Sunday Times, London

Continue to Plus page 8 * This deadly thing called grapevine

Return to the Plus contents page

![]()

| HOME PAGE | FRONT PAGE | EDITORIAL/OPINION | NEWS / COMMENT | BUSINESS

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to

info@suntimes.is.lk or to

webmaster@infolabs.is.lk