![]()

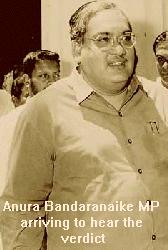

And the accused even in his evidence in court ( evidence-in-chief) had stated that he believed what was stated in the relevant article to be true. To quote from the accused’s evidence :

“ I believed it to be true. If there had been a doubt about it, it would have been withdrawn. “

On the same date the accused had further said: “ I have no reason to believe or suspect that the story to be false. If there was any suspicion it would have been withdrawn.”

But the accused had stated in evidence ( on 27 08.1996) that when Her Excellency the President complained regarding the article which article stated that she ( the President) attended Mr. Asita Perera’s birthday party, when in fact, she had not he (the accused ) contacted Mr.Navin Gunaratne and asked him (Mr. Gunaratne) whether, in fact the President attended the birthday party of Mr. Asita Perera obviously because the accused had not taken (at its face value) the President’s protest that she did not attend. To quote from the accused’s evidence:

Q : On the last occasion you said you questioned Navin Gunaratne?

A: Yes.

Q : How did you come to know that Navin Gunaratne attended the party ?

A .: I asked him whether he attended the party.

Q : What made you think that he attended the party?

I know he -is a close friend of the complainant and’Perera.

( In the above answer by the term “ complainant” the accused meant Her Excellency the President-)

Q : His answer was when he was there she never came?

A : Yes.

You asked him whether it was possible that she could have come after he left the party?

Further, the accused had said.

“When I asked him whether the President was there at the party he said “no”. Then I asked him whether it was possible that she came after he left for which he said it is possible.”

The above evidence of the accused makes it clear that he (the accused) on his own had questioned Mr. Navin Gunaratne to ascertain from him (Mr. Navin Gunaratne) as to whether the President attended the party because he (the accused) had correctly conjectured, as it turned out to be that Mr. Navin Gunaratne, being a friend of Mr. Asita Perera would have attended the latter (Mr. Asita Perera’s ) birthday party. And when Mr.Navin Gunaratne had indicated to the accused that Her Excellency the President did not attend the party so long as he (Mr. Navin Gunaratne) was there - the accused did not stop short at that - for he (the accused) went to the extent of asking Mr.Navin Gunaratne whether the President could have attended the birthday party after Mr.Navin Gunaratne had left. But, strange to say, the accused, had omitted to ask the writer himself although the writer in his article, as pointed out above, had stated that he himself witnessed the entry of Her Excellency the President by the rear entrance. To quote from the article: “ But this time the President was more circumspect about her appearance and used the rear entrance of the hotel watched by myself.”

It

is not to be forgotten that the accused, as pointed out above, had stated that

he believed what the writer had stated in the article concerning the President

and in the light of that belief the obvious thing one would have expected the

accused to do was not to question Mr.Navin Gunaratne (whom he only surmised

would have attended the party) but to have questioned the writer himself who,

was at hand and who had stated in the article itself that he saw the President

entering the hotel. Questioning Mr.Navin Gunaratne, as the accused had, in fact,

done, but refraining from asking the writer (who had stated in the article

itself that he saw the President entering) is such conduct as is irrational in

the extreme, if, in fact, the accused was not the writer but somebody else was.

But such conduct, that is, refraining from questioning the writer himself (to

ascertain whether Her Excellency the President, in fact, attended the party) is

wholly rational and quite understandable when the accused himself was the writer

for he had nobody to question but himself. (The accused’s evidence to the

effect that he did not question the writer had been cited above at page 137

hereof )

It

is not to be forgotten that the accused, as pointed out above, had stated that

he believed what the writer had stated in the article concerning the President

and in the light of that belief the obvious thing one would have expected the

accused to do was not to question Mr.Navin Gunaratne (whom he only surmised

would have attended the party) but to have questioned the writer himself who,

was at hand and who had stated in the article itself that he saw the President

entering the hotel. Questioning Mr.Navin Gunaratne, as the accused had, in fact,

done, but refraining from asking the writer (who had stated in the article

itself that he saw the President entering) is such conduct as is irrational in

the extreme, if, in fact, the accused was not the writer but somebody else was.

But such conduct, that is, refraining from questioning the writer himself (to

ascertain whether Her Excellency the President, in fact, attended the party) is

wholly rational and quite understandable when the accused himself was the writer

for he had nobody to question but himself. (The accused’s evidence to the

effect that he did not question the writer had been cited above at page 137

hereof )

It is worth notice that each item of evidence of circumstantial evidence enumerated above supports the same inference or the conclusion that the accused himself is the writer and there is a very high degree of certainty that inference is true. Confluence of those facts referred to above creates a cumulative effect too potent to resist that none but the accused himself was the writer - the weight and bearing of the circumstances (considered above) pointing to no other finding.

The accused had freely conceded that he knew who wrote the relevant article. The accused-editor cannot be allowed to brazen it out when common sense would suggest that if he was not the writer he (the accused) would disclose who, in fact, was the actual writer. The accused was stubbornly silent on the question as to who the writer was although he (the accused) was incessantly plied with innumerable questions on that score. But his silence says it for him - that no one else but he himself was the writer - particularly in the light of other facts referred to above.

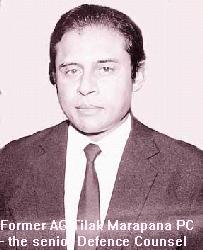

In the local case that had been cited to me at the argument, i.e. Vaikuntavasan Vs Queen 56 NLR 102 - the accused - editor had proved convincingly that he was absent continuously during the months of April and May 1952 and that he was in Jaffna promoting his own candidature at the parliamentary elections when the article in question in that case was published. The newspaper had been published in Colombo. Although the learned District Judge accepted that evidence without any reservations - still the accused-editor was convicted by the District Judge - although, of course, the conviction was quashed in appeal. It is to be observed that in that case, i.e. in Vaikuntavasan’s case, it had been proved by the accused that he had made arrangements for the newspaper to be published during his absence by someone else whose name was disclosed by him. Apart from anything else, apart from the several circumstances outlined above, there is always the presumptive liability of the editor and that liability could be displaced according to a case referred at page 838 of Law of Crimes by Ejaz Ahamed only by proving that the accused-editor was absent from duty for a bona-fide purpose at the time of publication of defamatory matter and that the work of editing was entrusted to someone else whose name should be disclosed. In another case referred to at the same page in the above treatise - it was held that when the printer of a newspaper pleads absence, in good faith he (the printer) should prove who was, in fact, the printer in his absence. It is a time-honoured and inveterate principle in the law of evidence that the capacity or the ability to give relevant evidence affects the burden of proof.

The law will not force a person to prove or show a thing which lies not within his knowledge. The fact as to who wrote the relevant article was clearly within the knowledge of the accused, as freely admitted by him but not within the ken or range of knowledge of the prosecution.

Thus, upon an analytical survey of the evidence and circumstances (as had been done above) the finding that the accused-editor himself was the writer of the article relevant to the indictment is as compelling a necessity as it (finding) is logical. Enthusiasm for the presumed innocence of the accused must be moderated by the pragmatic need to make criminal justice realistic. It is clear that the fact that the accused was the writer of the relevant article is proved beyond a reasonable doubt because I am satisfied as to feel sure. As stated in the “Law of Evidence” - (Elliot and Phipson) - page 72 (12th edition by D.W.Elliot - “beyond reasonable doubt” - does not mean beyond a shadow of doubt for as Lord Denning said in Miller Vs. Ministry of Pensions (1947) 2 AER 372 - “ The law would fail to protect the community if it admitted fanciful possibilities to deflect the course of justice.” In this case there is not even a fanciful possibility that somebody other than the accused-editor was the writer for if that was so - as stated above - common sense would suggest that he ( the accused) would have disclosed the name of that other person, at least, for the sake of diverting suspicions from him (the accused).

Next, to deal with, the 2nd ground referred to above at page 200 hereof on which the accused - editor can alternatively and also additionally be held to have made the publication of the offending excerpt, or to have caused the publication thereof - ( and so held criminally liable on the 1st count itself) - the accused must be held to have participated in the publication of the relevant excerpt inasmuch as he, being the editor, who had complete control or right to remove any offending passages or articles and so prevent publication, thereof had failed to remove the excerpt in question even after he had admittedly seen the relevant excerpt and read it ( to use the accused’s own words) “just before the publication “ and had, in fact, sanctioned the publication of the relevant article. (The accused ought to be convicted on this 2nd ground on the 1st count - even on the assumption that the accused was not the writer.) To illustrate the applicability or the operation of this ground or principle of liability it is needful to refer to one or two decided cases and also to remember that the concept of publication is the same in criminal as well as under civil law, that is, if an act or omission can be held to be publication in terms of civil law the same (act or omission) will be tantamount to publication in terms of criminal law as well and vice versa. In Hird vs Wood referred to in the judgment of Slesser L.J. at page 835 - (1937) K.B - Some unknown person had suspended a placard, containing defamatory matter between 2 poles on a roadway. But another-person remained there for a long time (leisurely) smoking a pipe and he (the other person) continually pointed at the placard with his finger and thereby attracted to it the attention of all who passed by. The Court of Appeal consisting of Lord Asher M.R., Lopes and Davey L.JJ. held that the conduct of the man (who kept on pointing at the placard ) constituted evidence of publication. The fact that I wish to bring into prominence, in this regard, is that there was no proof whatever that the man who kept pointing to the placard was its writer although his afore-mentioned conduct was held to be tantamount to publication. Then, in the case of Byrne Vs Deene (1937) 1 K.B. 818 - the facts were shortly as follows :-Some one (again an unknown person ) had put up on the wall of a club a placard containing what one may call a doggerel verse which was defamatory. It was held that since the defendants, who had complete control of the walls of the club, had not removed the placard or paper after they had seen it - the publication had been made with their approval. Greer L.J. said that “ the two defendants (who had control of the walls) by allowing the statement to remain on the wall of the club were taking part in the publication of it”.

Thus, it is clear and well-settled -that failure to remove defamatory matter constitutes publication. Of course, as stated by C.D.Baker (senior Lecturer in the University of Adelaide in his treatise on Tort (page 283) there must be control by the defendant, (in this case by the accused-editor) over the place where the defamatory statement appears which, in this case, was the issue of Sunday Times of 19.02.1995.

There is no disputing the fact that the accused being the editor had full control over the selection of material to be published in his newspaper.

On 03.07.1996 the accused-editor, be it noted, in answer to court, had said thus. To court :-

“Q : Is it your position that this article alleged to be defamatory and in respect of which you have been indicted was published without your knowledge?

A : I saw the article.

Q : When did you see the article?

A : Just before the publication.”

It is illuminating to point out that the recording of the above answer in Sinhala proceeding is in identical terms and read thus :-

The answer had been recorded in exactly the same words (by the English stenographer) that the accused used and the same questions and answers had been translated into Sinhalese and recorded by the Sinhala stenographer. (The fact that the accused desired to give evidence in English calls for mention as also the fact that the proceedings were recorded in English on the application of the defence.)

But, thereafter, on a subsequent trial date i.e. on 27.08.1996 the accused, under cross-examination by the learned Deputy Solicitor- General stated that he (the accused) saw the relevant article only after the publication of the provincial edition (that being the earlier edition) but before the publication of the city edition thereby seeking to alter the position he had so distinctly enunciated on 03.07.1996 viz., that he saw the article (to use the accused’s own words): “just before the publication.”

Thereafter when the accused so altered or varied his position, the learned Deputy Solicitor-General cross-examined the accused as follows :-

“Q : Your position is that for the first time you saw the gossip column after it was in fact published ?

A : Yes, in the provincial edition.”

On the previous date, i.e. on 03.07.1996 when the accused was questioned by the court, he (the accused) never never said that he saw the relevant article only after it was published in the provincial edition and of that fact I am sure, if of no other. The question put by the court was the last question asked ( at the end of that day’s proceedings) on 03.07.1996 and it had been asked at a time when it was least expected, and as it had turned out to be, at the psychological moment.

But when the learned Deputy Solicitor-General continued the cross-examination of the accused on 27.08,1996 in that regard the accused altered his stance ( as enunciated on 03.07.1996) and stated differently as follows :-

“Q : Did you tell that you, in fact, saw this article prior to the publication in answer, to court ?

A: I cannot recall.”

To reproduce the excerpts of the answers given by the accused on a later date i.e. on 27.08.1996 in regard to the same point:

“Q: You were asked this question by the court at page 6 of the proceedings of 3rd July 1996 ?

To court :-

Q : Can you recall the question ?

A: I cannot.”

Further cross-examination by the learned Deputy Solicitor-General concerning the same point proceeded as follows:-

“Q : Were you asked the question by court is it your position that the article alleged to be defamatory was published without your knowledge ?

A : I think I was asked that question by the court.

Q : You gave the answer you saw the article?

A : Yes, I think I recall the answer.”

But, now the accused by degrees recalls ( as his above answers show) both the question and the answer although he had stated, a short while before that, that he couldn’t recollect either the question or the answer that he gave i.e. on 03.07.1996 ( in answer to court) which was that he saw the relevant article : “Just before the publication.”

The fact that the accused had un-reservedly told court on 03.07.1996 without any qualification whatever, that he read the article relevant to the indictment “ before the publication” is borne out to a remarkable degree by the accused’s own evidence given even, on the same trial date, i.e. on 27th August 1996 although on that date too, he sought ( at one stage ) to make it appear that he read it after the publication of the provincial edition of the Sunday Times. On the 27th August 1996 the accused-editor giving evidence under further cross-examination had said thus :-

“ Q : Even prior to the publication of the provincial edition the relevant page would have come to you ?

A : That would have been sent in proof. I cannot recall whether I was there or not. If I was there they would have sent it to me. I am not hundred percent sure whether this page was sent to me before the publication of the provincial edition.” And the accused in his evidence had not stated that he was not there in the office which prevented him from reading the article in question or the gossip column before, it was published in the provincial edition which was the earlier edition - the city edition being the later edition. And the accused had also said on 25.09.1996 (10.20 a.m.) that he would not have neglected to read the article in question being read by him if it was sent to him.

“ Q : You admitted that you do not exclude the possibility of the article in proof being sent to you?

A : Yes, being sent to me.

Q : If it was sent to you then is it that you neglected to read it ?

A : I do not say neglected to read; quite often merely they send a proof page I do not go through it.

Q : Proof page is sent to you to read it ?

A : Yes

.....If I can read it; there is no mandatory requirement.”

But the accused distinctly remembers that a photo-copy of the page containing the relevant gossip column( which page later appeared in the city edition) was sent to him and that he read it prior to the publication of the city edition of the Sunday Times - city edition being the later edition.

On 27.08.1996 the accused had stated in his evidence thus :-

“Q : After the publication of the provincial edition but before the publication of the city edition you got a copy of the page which carried the article relevant to the case ?

A : There were some changes.

Q : In what form was the page ?

A : It was a photocopy.

Q . That photocopy was the page that appeared in the city edition ?

A : Yes.

Q : Why was the photocopy of that page that carried the relevant article sent to you?

A : When there was a change it was sent to me.

Q : Why was it sent to the editor?

A : I was there if I wanted to make any changes I could have done it.

Q : You did not read it?

A : I read it.

Q : When page 9 was in photocopy form did you read it ?

A : Yes.

( It was page 9 that carried the relevant article in both editions of Sunday Times )

Q : That was the page that subsequently appeared in the city edition ?

A : Yes.

Q : You said that the photocopy of page 9 was sent to you prior to the publication of the city edition?

A : Yes.”

Return to News/Comments Contents Page

![]()

| HOME PAGE | FRONT PAGE | EDITORIAL/OPINION | PLUS | TIMESPORTS

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to

info@suntimes.is.lk or to

webmaster@infolabs.is.lk