Barbara Sansoni: Shades of a pioneer

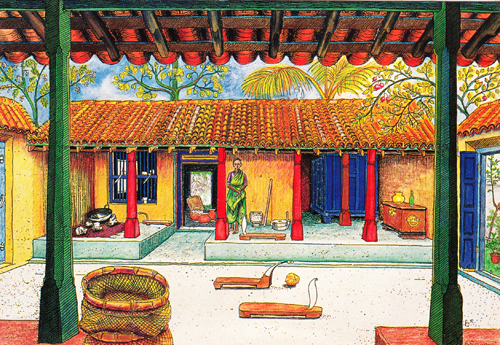

Her own style of drawing: The Jaffna Kitchen by Barbara

In April, Barbara Sansoni died at her home in Colombo, a few minutes after her 94th birthday. She was the last surviving member of a pioneering group of creative designers and makers, among them Bevis and Geoffrey Bawa, Ena de Silva and Laki Senanayake, who were born during the final decades of the British colonial period and sprang forth like uncoiled springs after Ceylon regained its independence.

She was born in Kandy, the daughter of Rex and Bertha Daniel. Her father was a Government Agent in the Ceylon Civil Service and the family lived in a series of colonial bungalows in different parts of Ceylon. Her mother was a Van Langenberg, the sister of arts impresario Arthur Van Langenberg, and she grew up in that carefree Burgher milieu that Michael Ondaatje would later describe in his book ‘Running in the Family’.

Barbara Daniel was brought up a Catholic and at the age of ten was sent to a convent boarding school in South India where she remained during World War II. After the war she moved to London and studied at Chelsea Art School for four years. Back in Ceylon, she married Hildon Sansoni, a man much older than herself who was a naval officer and a former aide-de-camp to the British Governor.

Barbara Sansoni: A portrait by Dominic Sansoni

Her involvement in weaving began in 1958 after the birth of her two sons. After independence the government sought to encourage weaving as a cottage industry as part of a drive towards self-sufficiency and, at the end of the 1950s, the nuns of the Good Shepherd Convent started a weaving centre at Nayakakanda to the north of Colombo. This was part of a programme to help ‘fallen women’ that was run by an Irish nun called Mother Good Counsel and it was she who persuaded Barbara to put her training to some use and work with them as a designer: “You will ensure that they never make anything ugly and that their work will be their pleasure and joy”.

Initially, the cotton was imported from Egypt but, when this was no longer obtainable, Barbara started dyeing Indian cotton using dyes imported from Switzerland. She began to experiment with colour and developed new weaving patterns inspired by the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian and the Bauhaus designer Josef Albers.

After 1962, she started to sell fabric and ready-made clothing from her home in Anderson Road under the name ‘Barbara Sansoni Fabrics’, using government yarn and working together with a number of rural weaving cooperatives. In the early 1970s she opened two shops: one in the Fort called ‘House’ that specialised in household fabrics; the other in Galle Face Court that sold clothes and was called ‘Barefoot’. At this time, she pioneered the reddha, a brightly dyed cloth that could be used as a wall-hanging or a bedspread but could also be worn as a wrap in conjunction with a cotton bodice. She also designed a variety of blouses and skirts for women and brightly coloured sarongs and shirts for men.

At the same time, perhaps inspired by memories of her peripatetic childhood, Barbara developed an interest in the architecture of Ceylon’s past and teamed up with Ulrik Plesner, the architect who had recently designed a new annexe to her house, and artists Laki Senanayake and Ismeth Raheem, to identify and record outstanding examples of buildings of different communities and from different periods. She claimed that she had learned little at art school and that the project forced her to develop her own her inimitable style of drawing. It also resulted in a series of newspaper articles which, little by little, revealed to the public details of a forgotten heritage which was at risk.

She also began to work collaboratively with architects, contributing terra cotta ‘Stations of the Cross’ to Geoffrey Bawa’s convent chapel in Bandarawela and decorating the staircases and toilet pods of his Montessori school for The Good Shepherd Convent in Colombo. Later she would develop colour schemes for the SOS Children’s Villages designed by architect C. Anjalendran.

The 1970s witnessed an influx of tourists and many of the new hotels used Sansoni fabrics for their table linen and soft furnishings. Her vibrant colours and strong designs made a big impact and many visitors returned home laden with her fabrics, clothes, bags and toys. This success led in turn to the development of a successful export business which operated from a purpose-built office on Green Path.

Hildon Sansoni died in 1979 and his place in the company was taken by his younger son Dominic who was by now a qualified photographer and who somehow managed to juggle his career with a growing commitment to the company that his mother had founded. ‘Barefoot’ moved to a rambling property at 706 Galle Road from where it offered an astonishing range of clothing, soft-furnishings and children’s toys.

In 1983 Barbara married the architectural historian Ronald Lewcock and started to divide her time between Colombo and homes in Australia and Britain. With his support she continued to look at and record old buildings, and it was he, in 1998, who pushed her into publishing the marvellous book ‘Architecture of an Island’ in which his texts amplified the huge collection of drawings that she and Laki Senanayake had produced.

Barefoot in the meantime became a multi-faceted empire employing over five hundred people and exporting its unique range of artefacts to countries around the world. However, it continued to produce its own handlooms and dye its own yarn and most of its products were designed by its own in-house team and made by its own network of craftspeople. Over the years, the shop in Galle Road grew like an amoeba to include a book shop, an art gallery and a lively outdoor café and performance space. More than just a shop, it became a place where people could meet to eat and drink, listen to live jazz, look at the work of up-and-coming artists and talk. And there were times, during the dark days of the civil war, when it was one of the very few places in Colombo where any of that was possible.

Barbara Sansoni didn’t invent colour in Ceylon – it was always there, hidden perhaps by the shadows cast by more than four centuries of colonial hegemony. But she certainly opened everyone’s eyes to it! Her brightly woven handlooms were a revelation and made a huge impact on a new generation of Sri Lankans. In 2004 Barefoot held an exhibition to celebrate forty years of weaving and design. In its catalogue, Barbara described how her colour sense was heightened by her experience of the landscapes and seascapes, the flora and fauna of Sri Lanka. In a series of remarkable paired images, she demonstrated how her colour combinations were inspired by nature: peacocks flying in Yala, hill terraces, a bamboo forest, a striped squirrel-fish.

Barbara was a larger-than-life character, a woman of strong opinions who would always stand out in a crowd. Much of what she did was ground-breaking, though she was so successful that her achievements were eventually absorbed into the mainstream and lost their power to shock. However, it should not be forgotten that she was a pioneer and that with Barefoot, like Terrance Conran with Habitat in Britain, she exerted a huge influence on how a new generation of Sri Lankans saw themselves, dressed themselves and lived their lives.

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.