From ancient times, a monastery amidst rock and jungle

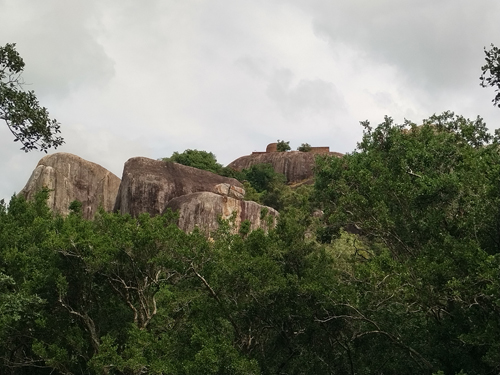

Rising above the jungle: The ancient rocks of Kudumbigala with Balumgala seen at right with the stupa on top. Pix by Pamal Yapa

We cheered at our first sight of Kudumbigala forest monastery, its rocks rising up like gigantic elephants amidst swathes of wilderness. We had driven down the cinnamon coloured track turning to the right off the road to Kumana, part of Digamadulla and specifically Panampattuwa, where in the thick jungle are many shrines still unknown to archaeology or history.

We were in Digamadulla (modern Ampara) to get to know the shrines; from Muhudu Maha Vihara and Bambaragastalawa to Shastrawela, the latter two still slumbering deep in jungle tide like so many others.

The land here – apart from once being an ancient civilization – is imbued with a feel of primal mystery, where legends of a large fierce subspecies of leopard called Lenama koti still prowl, and villagers hand down tales of dwarf hominids called Nittaewo (hairy cannibals) and kampoththo (even smaller hominids, with large ears they cover themselves with while sleeping) as having once preyed on their ancestors and the (now extinct) Veddahs of the area.

Impossible as some of these may sound, being in this beautiful landscape it is hard to shrug them off; they cling like the salty air and the timeless rock and jungle.

Kudumbigala as a monastery probably goes back to the time of the pious prince Gothabhaya (250 to 205 BC), a scion of Ruhuna who must have dedicated the 105 currently known caves to monks. The cave count is as of 1980, when the Ven. Ellawala Medhananda wrote his erudite book, and leaves the possibility of as much as a hundred more caves undiscovered by modernity in nooks and crannies of the jungles.

The Maha Sudassana lena: The main cave among two hundred. Pic by Jayal Yapa

The ground level buildings of Kudumbigala consist of a simple refectory where all monks gather to eat; and modest, simple offices.

From here wends up a stairway, part of it which feels like a roofless tunnel, because we clamber between two narrow rock walls, where to meet a leopard or bear (as often happen to monks) would be a conundrum indeed!

One of the most interesting sights is the main cave – Maha Sudassana lena – which today has a whitewashed façade- like a Kandyan len vihara but with no adornments.

The cave is special because it is connected to the rediscovery of Kudumbigala in the 1950s by the Ven. Thambugala Anandasiri, who, invited by a rather singular lay devotee came here to the wilderness and stayed in this cave, then with just a drip ledge, till, years later, a monastery was again rejuvenated.

The Maha Sudassana Lena has a large, white sand compound which commands a matchless view of the jungle sloping down to the far below Selewa eliya beach and sea, the fishing craft seen like twinkling pinpoints of light at night.

In such caves the monks still live, cheek by jowl with wildlife. In his memoirs that brave monk Ven. Anandasiri has left myriad encounters with wild beasts including the mysterious Lenama kotiya which he says was unusually large and had stripes as well as spots.

If you take the path to the left of Maha Sudassana lena, you come to the foot of the sheer rock called Segiri Balumgala (‘the rock with stupas cum vantage point’).

After a perilous climb on steps which are gashes cut on rock, you reach the top of this the tallest rock of Kudumbigala which takes your breath away literally and metaphorically.

Here the noon wind was howling wildly, but perched around us were three stupas. The chief of them is cylindrical, and stands like the mystery it is in strange silence. It is the one and only cylindrical stupa in Sri Lanka, and its only known twin in the world is the massive Dhammika Stupa of Saranath.

Remember the precipices are steep indeed, however, you will be drawn by the panorama below like a map of Digamadulla – a heady sight with vehicles crawling like ants down roads amidst water and jungle and sea.

There is another rock to scale. This to be reached by the path leading up from the left of Maha Sudassana lena. Some of the other identified stupas (a total of eight) can be seen there.

Unique: The only cylindrical stupa in the country

After a trek through more jungle you arrive at this rock, Sumanakuta, which is a sight for sore eyes. Here on the gal thalaawa rock (that you had already seen from the cinnamon coloured track you drove down to get here) are many remnants of stupas and buildings in ruins, overgrown with wild grass and stone pillars with clear ponds where pink lotuses bloom.

From all sides of this vast rock, you can get panoramas of the country around.

Kudumbigala’s old name, incidentally, was Cetiya Pabbatha, ‘the mountain with many stupas’, a name it shares with Mihintale. This monastery however is unsullied by sophistication or any kitsch decoration- though after the demise of the pioneering monk Anandasiri, some modern statuary and garish decoration have been added. These we felt the hermitage could do without.

During Ven. Anandasiri’s first year here, 1954, a rather incognizant Englishman visited Kudumbigala, still barely retouched by civilization, and was to write a few articles on the jungle monastery when back home.

He was to describe the skulls of animals (ranging from elephant to bear, leopard and crocodile), used for impermanence meditation, as parts of black magic.

However, the misguided articles were to draw hither the Oxford anthropologist Michael Carrithers, whose long sojourns resulted in the magnificent book The Forest Monks of Sri Lanka.

As we clambered down again, the day had turned mellow and the monks were getting ready for the evening devotion and the jungle too was haunted by calls of animals. As we resumed our journey through the wilderness back to Digamadulla’s core, we caught a glimpse of the balumgala at dusk in the distance with its mystery stupa, and were touched by how we lucky we were to have such wild sanctuaries of the spirit – untouched by human rapacity.

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.