Making sense of loss through artistic exploration

When halfway through our conversation on his first solo exhibition, Ajantha Ranaweera opens up the plain little notebook he carries with him it is quite a revelation; on one page, there are arresting sketches of an unusual gopuram and on another a geometrical lamp, coping details for walls, furniture layouts, even a design for a simple laundry box – sure strokes of pen and precise notes alongside.

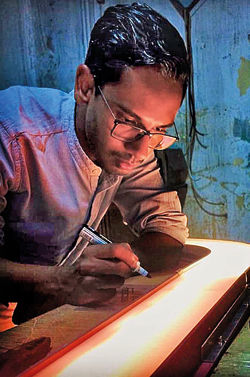

Chartered architect, artist and designer to boot, Ajantha, it is clear, has a prodigious thirst for exploration and expression which sees few boundaries. He is constantly experimenting – markers, cinnamon sticks and dip pens can be tools of the moment as he paints or toys with digital images well past the midnight hour, sometimes till 2 or 3 in the morning as the mood takes him.

Chartered architect, artist and designer to boot, Ajantha, it is clear, has a prodigious thirst for exploration and expression which sees few boundaries. He is constantly experimenting – markers, cinnamon sticks and dip pens can be tools of the moment as he paints or toys with digital images well past the midnight hour, sometimes till 2 or 3 in the morning as the mood takes him.

‘The Boy in Paradise’ which runs through October at the Paradise Road Galleries is an ambitious debut, a collection of sketches of an introspective journey born of the disappearance of a loved one progressing onto many planes – from loss and grief and beyond into a blissful place of sanctuary.

It is a dialogue that began within. He is unequivocal that he is not setting out to make any political statements as an artist. Often when such a loss occurs, it is the event that becomes the focus, not the person who is lost or the life they had. Loss, whether from death or disappearance, he says, is never easy to confront and hence, the blurring of worlds from the raw intensity of grief and mute incomprehension that sometimes accompanies it, to the struggle to make sense of it. For him, this has emerged in this collection of paintings both figurative and abstract.

Cherishing their memory: Two paintings from the exhibition

My main idea was how do we start up a dialogue on this, he asks, for he is all too aware that this is a shared experience, that many in this country may relate to. The understanding that some issues are never black and white, more likely clouded in grey, brings with it the hope of more open dialogue, however difficult, from a safe platform of mutual respect.

His artist’s statement describes the lost boys in the paintings in a metaphysical world, ‘in shifting fantasy realms’. “Far from worldly strife they sleep, frolic in gardens, peeking through foliage, floating in boulder pools and water channels joyful and safe in the gardens of utopia. The gardens are equally stylized with varying scales and proportions that subvert reference to a familiar uni-dimensional material world.”

His representation of paradise is a beautiful Sri Lankan ‘native garden’ he calls it – an abstract landscape of winding pathways, stylized paddy fields and banana leaves, reed beds, seen evolving from blocks, into splashes of colour flowing into nothingness, to reach nothingness.

“We begin to understand those left behind are not alone on this journey. We could regard disappearance as simultaneously containing loss and joy – we cherish the memories of those loved ones who have left us by seeing them in states of bliss. We know and understand death is life in the continuum of samsara.”

While the exhibition will draw attention to his art, for Ajantha his art, architecture, design are inextricably bound. It’s impossible for him to isolate them, for they are all interwoven in his life as glimpses of his sketchbook reveal, ideas overlapping and fuelling his creativity.

Ajantha in design mode working on a light fitting

Creative and artistic as a child, though initially aiming to be a marine biologist, when called upon to advise his aunt on paint colours for the house she was building, Ajantha found it an exhilarating process and it got him contemplating the prospect of architecture.

At the City School of Architecture (CSA) where he says, he enjoyed every single day of his studies, he would have the good fortune to meet two singular personalities who have greatly impacted his thinking. Anjalendran, his master in that first year at CSA opened up a whole new appreciation of art and form introducing him not only to contemporary greats like Ena de Silva and Laki Senanayake but also a wider world of art and antiquities. Ajantha went on to work with the renowned architect as a draughtsman doing architectural drawings and measured drawings for his book ‘The Architectural Heritage of Sri Lanka: Measured Drawings from the Anjalendran Studio’ and relates the fun of unscripted journeys here and overseas to India and Austria.

With architect-historian Dr. Shanti Jayewardene, it has been a more cerebral experience. She taught him in his fifth year at CSA and he was soon volunteering his services as one of the principal photographers for her seminal volume ‘Geoffrey Manning Bawa: Decolonizing Architecture’, for which he also contributed sketches and graphics. In their travels for the book, he saw Sri Lanka’s ancient archaeological sites with new awareness for, the Bawa trail aside, their discussions veered to the larger discourse beyond the nuts and bolts of architecture, of heritage, decolonization narrative, to the nexus between art and culture, art and history, art and society, the writings of Edward Said, Ananda Coomaraswamy, Gananath Obeyesekere, to Sujit Sivasunderam and T. Shaanathanan. Those discussions still continue.

His architectural experience has been built on a solid foundation, working with not only Anjalendran, but other well known practitioners Philip Weeraratne, Dylan Holsinger and Cecil Balmond and with consortiums such as Pinnacle and Design One (Pvt) Ltd. The pandemic was not the best time to start a new venture, Ajantha remarks wryly, but he branched out on his own in January this year, launching Dvara Architects and Designers (Pvt) Ltd - Dvara in Sanskrit meaning a door, or gateway.

And whilst preparations for ‘The Boy in Paradise’ were reaching the final stages last week, Ajantha was off in pursuit of a different garden project, this time allied with bridges being built in Anuradhapura. It seems safe to predict, that whether in art, architecture, sculpture, design, we are going to hear more of him in the future.

Ajantha Ranaweera’s exhibition ‘The Boy in Paradise’ is on at the Paradise Road Galleries, Colombo 3, this month.