Sunday Times 2

Anagarika Dharmapala, the Buddha-Gaya temple and the campaign he launched

View(s):September 17 is the 157th birth anniversary of Anagarika Dharmapala, founder of the Maha Bodhi Society. At the turn of the 20th century, he launched a campaign to have the holiest of sites of the world’s Buddhists be brought under the managerial control of Buddhists. Jairam Ramesh, an Indian MP and former Union Minister, refers to this campaign in his new book “The Light of Asia – the poem that defined the BUDDHA. Extracts;

Many historians have written books and learned papers on the issue of the Mahabodhi Temple. The historical background to the dispute that lasted almost seven decades is a long and convoluted one. But certain basics are not contested.

First, ten years after his consecration, that is in around 259-8 bce, the Mauryan ruler Ashoka visited the hallowed Bodhi tree under which the Buddha had gained enlightenment. Second, a century or so later ‘a representation at the Buddhist stupa of Bharhut in Central India depicted a throne, with the trunk of the Bodhi tree behind, surrounded by an open-pillared pavilion’ and ‘this throne was most probably erected by Ashoka at Bodh Gaya’.

The Anagarika (seated) at Buddha Gaya with the Japanese monk

Third, various types of structures, including some form of a temple, were built over time to honour the Buddha, with the temple having undergone reconstruction around the fifth century bce. Fourth, as Buddhism began to gradually fade away (and the process was gradual ) Hindu icons came to be worshipped too in its precincts. Over the centuries, the Buddha was also worshipped there, but as a Hindu deity.

Fifth, from the thirteenth century the Mahabodhi temple became a model that was emulated in other places like Burma and Siam. Sixth, the temple continued to draw visitors not only from India but also from Ceylon, Burma, Siam, Tibet, China and Japan.

Seventh, sometime in the last decade of the sixteenth century a wandering Sivaite sannyasi established his abode close to the ruins of the temple. In August 1727, a Mughal prince gave the Sivaites a deed to establish ownership rights in the area (although it was unclear whether the deed covered the actual temple or not). The Sivaites took control of the temple and its surroundings following the grant of the deed and from then on, both Hindus and Buddhists had access to it.

Eighth, repairs to the temple were carried out by Burmese Kings in the early nineteenth century, who continued their patronage till the time of the Third Anglo-Burmese War of November 1885.

In mid-January 1886, (Englishman Sir Edwin) Arnold visited the site of the sacred temple and the Bodhi-tree. What he saw anguished and angered him immensely. After his visit to Panadura in Ceylon and (during) his conversation with Weligama Sri Sumangala, Arnold had given a description of localities in the life-history of the Buddha that he had recently visited. The venerable Ceylonese monk expressed an ardent wish that the Buddhists might someday recover the guardianship of that sacred ground in Buddha-Gaya where “the Lord” meditated so long under the Bodhi tree and finally attained his Buddhaship.

Arnold also writes that Weligama Sri Sumangala had told him that the place where Buddha had received enlightenment and also the place where he entered into Nirvana ‘ought no longer to be in any hands except those of Buddhists’.

The picture would, however, be transformed with the entry of the Ceylonese Buddhist Anagarika Dharmapala into this story in early 1891. He is considered to be the key founding figure of Sinhala nationalism. Equally, for about four decades till his death in April 1933, Dharmapala was a one-man army for the recovery and revival of India’s Buddhist heritage and traditions.

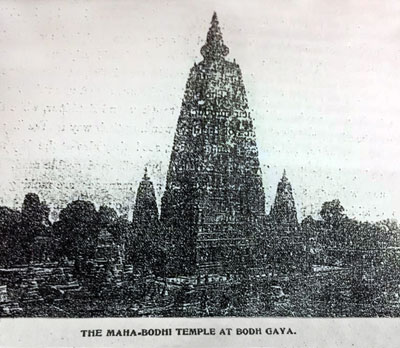

The Mahabodhi temple at Buddha Gaya

By his own accounts though, Dharmapala had read ‘India Revisited’ in 1886 and had been angered by Arnold’s account of the blasphemous goings-on at the Mahabodhi Temple. Three years later while convalescing in a hospital in Kyoto he would read The Light of Asia, finding in it ‘consolation and hope’.

On 22 January 1891, Dharmapala, accompanied by a Japanese priest and Pali scholar Kozen Gunaratna, reached Bodh Gaya. By his repeated later recollections, seeing how the Mahabodhi Temple had become essentially a place of worship for Hindus and getting a sense that its importance for the Buddhists was being treated with utter contempt by the Hindu priest, Dharmapala vowed that the Mahabodhi temple would ‘once again be a properly functioning Buddhist temple’.

On 31 May 1891 he founded the Mahabodhi Society in Colombo. Weligama Sri Sumangala, who had met Arnold in February 1886 and first spoken of Buddhist control over Buddha- Gaya, was its President, (Henry Steel) Olcott was its Director and Chief Adviser and Dharmapala its General Secretary. The managing committee had members from different parts of the world, with Arnold as one of its ‘London Representatives’.

In July 1891 four Ceylonese monks were sent to Buddha-Gaya on behalf of the Society, which would also organise an international conference there in October 1891. But realizing that all the action needed to get Buddhist control over the temple lay in the then capital of British India, Dharmapala moved the Society to Calcutta a year later.

On his way back from (The World Parliament of Religions) in Chicago, Dharmapala stopped off in Japan, where in November 1893 he was presented with a 700-year- old ancient Buddha image, enshrined in a temple at Kanagawa near Yokohoma. Dharmapala sought permission from the British government to install the Buddha image he had been given in the sanctum sanctorum of the Mahabodhi Temple. But the British prevaricated, worried about antagonizing Hindu sentiment and suspicious of Dharmapala’s Japanese links.

Finally, before sunrise on 25 February 1895 Dharmapala took unilateral action and entered the temple and placed the statue in its sanctum sanctorum, which was then empty. He was about to start worship when a group of armed men, clearly followers of the Mahant, themselves barged in, grabbed the statue and dumped it elsewhere. It was to be placed in the Burmese rest-house nearby. Dharmapala then decided to file criminal charges against the Mahant and his men for trespassing into a place of worship and for damaging religious property. It is instructive to note here that Dharmapala’s legal action went against all the advice he had received, including from Sumangala and Olcott, who were most probably aware that while the Buddhist right to pray in the Mahabodhi Temple was unimpeachable, their legal right to its ownership was ambiguous.

The case was first heard on 8 April 1895 by the local Magistrate D.J. Macpherson.

On 19 July 1895 Macpherson gave his judgment. He acquitted two of the defendants but held three of them in violation of the Indian Penal Code. They were fined and given a jail sentence of a month. On the larger issue of ownership of the Temple which Dharmapala was hoping to have settled definitively, the magistrate ruled that the ‘Mahant did enjoy possessory rights of a certain kind’ over the Temple and its precincts but that ‘they could not have thought these rights to be of so complete a character as to connote full proprietorship or carry with it the right claimed by the Mahant to do what he liked inside the temple’. Macpherson characterized the proprietorship of the temple as being one of ‘dual custodianship’ between the Mahant and the government. The government had come into the picture because of the restoration works it had carried out at Buddha-Gaya.

This was a partial victory for Dharmapala. But very soon the Mahant submitted an appeal in the district sessions court. The appeal was heard by Herbert Holmwood, who suspended the jail sentences but retained the fines. On 30 July 1895 he held that the Mahant’s proprietary rights over the temple and its surroundings found expression in the government’s own list of Ancient Monuments issued in 1886 but that this did not constitute a ‘deed or grant’.

The Mahant was still not satisfied and submitted a second appeal, this time to the Calcutta High Court. A two-judge bench delivered its verdict on 22 August 1895. It set aside both the fines and the jail sentences. More importantly, one of the judges (the British one) held that ‘if the temple is not vested with the Mahant, it does not appear to be vested with anyone’, while the other judge (an Indian) held that ‘the question of what the exact nature and extent of the Mahant’s control over the temple is, the evidence adduced in the case does not enable us to determine’.

Dharmapala had received a huge setback. One interesting feature of Dharmapala’s campaign was that newspapers run by Indians supported him whereas newspapers aligned to British interests were critical of him.

The Japanese idol would move to the headquarters of the Mahabodhi Society in Calcutta in 1910. Dharmapala would continue his campaign to get full Buddhist control over the temple at Buddha- Gaya. In 1922, the Indian National Congress would hold its annual session at Gaya and an appeal would be made to (Mahatma) Gandhi to have the issue resolved once and for all.

In 1922, he had pinned hopes on Gandhi for getting control over the Mahabodhi Temple at Buddha-Gaya and all that Gandhi had done was delegate that responsibility to his trusted lieutenant from Bihar, Rajendra Prasad. The man who would later become independent India’s first President toiled over the issue for the next quarter of a century.

n In 1949, two year’s after India’s Independence and 16 years after the passing away of Anagarika Dharmapala, The Maha Bodhi Temple Act was passed giving the Buddhists an equal voice in the joint-management committee of the holy site now referred to as Bodh Gaya or Buddha Gaya.