From the spiritual to performance

View(s): ‘What we have described in this book are the halcyon days of Kandyan dancing…..’

‘What we have described in this book are the halcyon days of Kandyan dancing…..’

-Amunugama

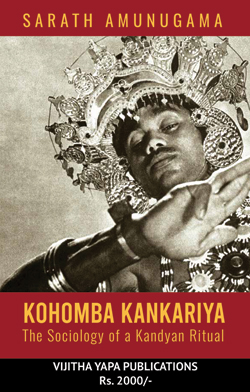

Sarath Amunugama has put out a new book and it is on the Kohomba Kankariya. This is the first book on the subject that I read, although there are three others in Sinhala in my collection. Two of them are collections of kavi and other statements in the ritual. None of them describes the performance of a Kankariya in detail, as Amunugama does.

Of them, the book that comes close to Amunugama’s concerns is that by Mudiyanse Dissanayake, an accomplished artist and teacher (one-time professor at the University of the Visual Arts in Colombo) of dancing. Dissanayake in the last chapter of his book deals with some concerns relevant to Amunugama’s subject matter: the sociology of the ritual. Amunugama’s Kohomba Kankariya is the first full length treatment of the subject. That is in contrast to the extensive attention paid to healing rituals in the southern coastal belt, by scholars, both local and foreign. I am personally familiar with actual performances of sooniyama, sanni yakuma and rata yakuma, having seen them when I was a child and never forgotten. I have never seen a Kohomba Kankariya live or on record.

Amunugama writes a fine account of a Kankariya performed in Rangamuwa in 2015 in a village near his parents’ home. He himself was the prime mover organising it. He also noted the distinction that other forms of dancing (pantheru, udakki, raban) in and around Kandy, undertaken by high caste persons. After all he is a ‘Kandy Man’. That itself makes reviewing this book difficult. It is partly personal and mostly professional.

The book consists of three essays: the first sets before us, in exquisite detail, the performance of the ritual in Rangamuwa. While doing so, he explains to us the sociology of what goes on. The second essay on Ves natum is an extraordinary foray into the emergence of scenes from rituals to the mainstream entertainment in Colombo: ‘….traditional culture….., shifting emphasis from ritual to commerce’. That shift was preceded by Kandyan dancing being introduced to western audiences, not as art but as acrobatics. The persons who brokered this transfer were a most unexpected lot. The third, the shortest is a collection of photographs, some in colour, of personages connected with the Rangamuva Kohomba Kankariya and other earlier celebrated dancers.

The reader would enjoy the systematic presentation of the Kankariya. Here, I will offer a few comments on the sociology of it, well aware that I, no sociologist, dares to comment on the writings of a most brilliant student of the subject in the country. Amunugama has an ambitious plan in this essay: ‘ …. what I am attempting here is to prepare a schematic ‘frame’ into which all or most rituals can be incorporated. …….all local healing rituals have the same basic format…’.

While the schemata that Amunugama presents is mostly complete, he misses a very substantial part of the suniyama. For several hours early in the following morning, yakdessa conduct various acts to remove all evil influences afflicting the aturaya. These include puhul kapima (cutting a cucumber), cutting tholabo (a kind of yam) kapima, dehi (lime) kapima, valalu kapima (the patient is put in a sort of cage made of cane and the cane is cut to set him/her free), symbolically removing all that afflicts him. Sirasa pada kavi comes in here. Finally, the whole atamagale, made of banana tree skins and gokkola (young coconut fronds) in which the aturaya sat all night, is cut down. All this furious activity with several yakdessa wielding knives is entirely exciting. It may be useful to consider that. Amunugama successfully analyses the Kankariya in terms of this schemata.

I found the second essay the most engaging. Its subtitle ‘From cosmic drama to street and stage spectacle’ announces to us the processes he analyses. The personages who facilitated that transfer of whom Amunugama writes are of equal interest, because those personages and dancers belonged in different worlds. But yesterday, Ves natum was in Kohomba Kankariya in villages in Kande Uda Rata. Today, Corona permitting, we sit in the comfort of the balcony of the Queen’s Hotel and watch Ves netum and in the Lionel Wendt to watch Chitrasena’s ‘Karadiya’ or Ravibandhu lead a drum ensemble. Ves dancers play before potentates in Colombo or conduct a bride and bridegroom to the poruva in Guruva pattu far distant from Harispattu.

How did that shift take place? What social forces enabled that change? Who were the agents who activated the process? Those are questions to which Amunugama provides answers, probably never final. The Kankariya and Ves netum were performed by men of the Berava caste, low in esteem in the hierarchy. Like almost all ritual healers among the Sinhalese, these ritualists tilled some land from which they derived a meagre income, which they supplemented with that from performing rituals. To dance before Europeans, to dance before royalty (Edward, the Prince of Wales) and before the Governor were some sort of manumission. When they travelled to Europe and US in late 19th century, and early 20th century as performers in circuses, they not only earned some money but also stood in altered relations to their foreign employers. For the Europeans, these dancers were exotic people from strange lands.

In 1917, P.B. Nugawela, a high caste potentate brought Ves natum to the Dalada perahera. Writes Amunugama, ‘…..the yakdessas…. had to be brought in as Sinhala society began to emerge from its feudal strait jacket’. The Ceylon National Congress, a political organization looking for identifying itself with national culture began to espouse Kandyan dancing. In the 1930s, Western educated aesthetes in Colombo, the 43 Group led by George Keyt, ‘discovered’ these dancers and dances. Their photographs were published in Europe. The dancers appeared in exhibitions in Europe. The dancers ‘….(moved) away from the Kankariya to enter the global stage as dance performers and drummers’. ‘Nittawela Gunaya, the finest exponent of the Kandyan dance on stage…. was not interested in the Kankariya ritual’. The same could be said of Sri Jayana. Those processes need further analysis.

A high official in the Department of Education in the late 1930s, S.L.B. Sapukotana, was enthusiastic about teaching Kandyan dancing in all schools. Such change would have given a new social status to members of the Berava caste and of course, raised their incomes. In 1947 or so, Mr. Punchi Banda arrived in the then remote little town Hikkaduwa, where I was a student, to teach Kandyan dancing. And we learnt the first steps ‘thei, thei’ and a few days later ‘thei kita, kita thei’. We first danced the musaladi (Tamil for a hare) vannama. That process has gone on and now many children in most schools learn Kandyan dancing.

The clothing of ritualists in the coastal belt have changed, influenced by the costumes of Kandyan dancers. The all-white cloth from the waist to the ankles that ritualists in the south wore, now has red and blue lines at the ankles. Drummers who sometimes tied a white piece of cloth round their heads now wear an elaborate headdress copying dancers in the Kandyan tradition. Many cultural practices from the hills have been adopted by those in the plains, e.g. wedding suits have changed from European to thuppotti. Brides now mostly commonly adorn themselves with Kandyan sari and matching jewellery. These phenomena, someone needs to inquire into.

The most striking transfer of rituals to the proscenium theatre was brought about by Ediriweera Sarachchandra, when he wrote and directed Maname Nadagama. The story was from the Jataka potha. It was a village ritual, more entertainment, that was played over seven evenings on a village heath. Sarachchandra brought it on stage as a sophisticated play that lasted a mere two hours. He went to the same well, the Jataka pota, for fresh themes and we had Kada Valalu (in which Amunugama acted), Pemato Jayato Soko, Loma Hansa while Hasti Kanta Mantare was from the Dhammapadattha kata. This well seems to have been beyond the depths of those that came after Sarachchandra. These are subjects for broader and deeper inquiry.

In the last essay Amunugama presents a series of ‘….photographs of the Kankariya and its associated personnel’. Here and elsewhere in the book, there are photographs of dancers like Gunaya, Suramba, his two sons Sumanaweera and Samaraweera and Chitrasena. There are also pictures of Lionel Wendt and George Keyt. I conclude.

| Book facts | |

| Kohomba Kankariya, The Sociology of a Kandyan Ritual by Sarath Amunugama (Vijitha Yapa Publications, Colombo, 2021, price Rs. 2000). Reviewed by Usvatte-aratchi |