In step with Ves as national symbol

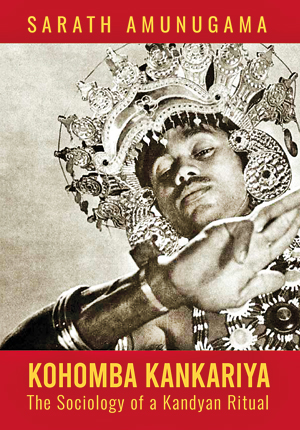

View(s): Dr Sarath Amunugama’s latest book ‘Kohomba Kankariya- The Sociology of a Kandyan Ritual’ has just been released. Many who know the author as a prominent political personality, may not be aware that he graduated from the University of Peradeniya with a degree in Social Anthropology and went on to gain a doctorate in the subject from the Centre for Advanced Social Studies in Paris. Born and raised in Kandy, Dr Amunugama, has retained his fascination for the folk rituals of the land and his book takes the reader on a journey of the rise of Kandyan dance and its evolution from ritual to performance against the political transformation of the country.

Dr Sarath Amunugama’s latest book ‘Kohomba Kankariya- The Sociology of a Kandyan Ritual’ has just been released. Many who know the author as a prominent political personality, may not be aware that he graduated from the University of Peradeniya with a degree in Social Anthropology and went on to gain a doctorate in the subject from the Centre for Advanced Social Studies in Paris. Born and raised in Kandy, Dr Amunugama, has retained his fascination for the folk rituals of the land and his book takes the reader on a journey of the rise of Kandyan dance and its evolution from ritual to performance against the political transformation of the country.

Published here is an extract from the book exclusive to the Sunday Times.

Punchi Banda Nugawela and

the induction of Ves

Who made the momentous, but perhaps inevitable, decision to introduce Ves to the Kandy Perehera? It was Punchi Banda Nugawela who was the Diyawadene Nilame during the period 1916 to 1937. He was an outstanding Radala of his time coming from a lineage that held office under the British and officiated as custodians of the Tooth Relic. He succeeded Cuda Banda Nugawela who died in 1916 as the Diyawadene Nilame. C.B. Nugawela was the father of Adigar Lawrence Nugawela who had been a great favourite of the Governor.

Who made the momentous, but perhaps inevitable, decision to introduce Ves to the Kandy Perehera? It was Punchi Banda Nugawela who was the Diyawadene Nilame during the period 1916 to 1937. He was an outstanding Radala of his time coming from a lineage that held office under the British and officiated as custodians of the Tooth Relic. He succeeded Cuda Banda Nugawela who died in 1916 as the Diyawadene Nilame. C.B. Nugawela was the father of Adigar Lawrence Nugawela who had been a great favourite of the Governor.

P.B. Nugawela who built his Beragama Walawwa to resemble a British manor which exists to this day, was a great benefactor of the Kankariya Paramparawa, especially the Tittapajjala group that lived in a village located virtually on the doorstep of the Walawwa. This is attested to by the fact that Beragama means the “village of the drums”. According to local tradition when the Yakdessas were reluctant to perform in the Perehera saying that they could not deviate from serving the gods, the DN assured them that the Dalada Perehera was the biggest ritual for the gods and they should accede to his request. Accordingly the first Ves performers were positioned to dance in front of the Dalada casket which was carried by the sacred elephant and not before the Nilame as done today. But, as Molamure points out once the protocol of the Kankariya was breached, over time the Ves Natum became the preferred dance of the Yakdessas and soon lost its magical character (De Zoete: 1957).

Nugawela’s innovation came in 1917. However much before that both Colonial officials and western circus masters had pulled them out of the Kankariya. It must be mentioned here that dancing in the Dalada Perahera is still considered a great honour by the participants. Nugawela’s initiative did not in any way diminish the performers’ sense of the sacred. However today the situation is somewhat different. Insiders know that both chiefs and dancers fortify themselves with a liberal intake of alcohol for the physically taxing business of parading the city ignoring the possible consequences of ‘Vas dos’. Since 1917, many distinguished visitors to Sri Lanka have witnessed the Perehera in Kandy and have been impressed largely because of its Ves Natum. Step by step it has been positioned as one of the great dance forms of Asia.

We will now proceed to describe how the local and international elite adopted and promoted this dance form. It is now a part of colonial and modern Sri Lankan history which has not been described by our historians. Crucially, Ves became an easily recognisable symbol for the local elites, especially the political elites, in their search for national authenticity and self pride. It became a tool in the hands of the political leadership of that time to assert the country’s cultural independence and its history as an independent community with a unique national identity. As if to get colonial recognition to that strategy, Lord Soulbury who led the committee which recommended far reaching constitutional changes and later became the Governor General was, as we shall see later, drafted into that conversation as an admirer of Kandyan dancing. In the UK, he had been the President of the Arts Council.

D. H. Lawrence in Kandy

Prince Edward Albert’s Visit in 1922

The second Prince of Wales, also named Edward Albert (1894-1972) and the nephew of the Royal visitor of 1876, arrived in Ceylon in 1922. He also was visiting Ceylon after a strenuous visit to India, We get to know more about his visit because two days after his arrival D.H. Lawrence, the famous English novelist and poet also arrived in the island for a six week tour. Lawrence was a guest of his friend Earl Brewster and his daughter in Kandy. Brewster who was interested in studying Buddhism in Ceylon had contacted Lawrence who was in Capri. This awoke Lawrence’s fantasies about the freedom enjoyed by non whites. “Palm trees and elephants and dark people incantevole” (enchanting) he wrote in Capri.

In his mind he contrasted that life with the prudish and intolerant mores of middle-class England which caused him much distress as a writer. He also at the same time had an invitation to go to Taos in Mexico but he decided to leave for Ceylon on a steamer that was heading from Naples to Sydney via Colombo. His stay in Kandy during which he visited Buddhist temples and monks was not a success though from his writings we know that he spent a considerable time gathering local impressions as we shall see shortly. Unlike Brewster, Lawrence was contemptuous of local beliefs and felt restricted by the overwhelming culture of the native people. On the 23rd of March, he was taken by his hosts to see the Raja Perehera in Kandy organized for the Prince of Wales. This encounter led to his poem “Elephant” which encapsulates his reaction to the “wild” ritual of the Perehera and the absence of “imperium” in the Western Christian Prince he describes as “a pale little wisp of a Prince of Wales”.

“Pale, dispirited Prince, with his chin on his hands, his nerves

Tired out,

Watching and hardly seeing the trunk-curl approach and

Clumsy knee lifting salaam

Of the hugest, oldest of beasts in the night and the fire-flare

below.

He is royalty, pale and dejected fragment up aloft.

And down below huge homage of shadowy beasts, bare foot

and trunk-lipped in the night.

Chieftans, three of them abreast, on foot

Strut like peg-tops, wound around with hundreds of yards

Of fine linen.

They glimmer with tissue of gold, and golden threads on a

jacket of velvet,

And their faces are dark, and fat, and important.

They are royalty, dark faced royalty, showing the conscious

Whites of their eyes

And stepping in homage, stubborn, to that nervous pale lad

Up there.”

And how does Lawrence describe the Kandyan dancers in the Perehera? He weaves his impressions into his feeling of the absurdity of the Prince’s motto which is decorated with three symbolic feathers saying “Ich Dien” which means “I serve”. However, for Lawrence the message of tradition on display is quite different:

“And to say to them Dien Ihr, Dien

Omnes, vos omnes, servite,

Serve me, I am meet to be served

Being Royal of the gods.”

Then he turns to the dancers and drummers he sees in the Perehera.

“Men-peasants from jungle villages dancing and running with

Sweat and laughing,

Naked dark men with ornaments on, on their naked arms

And their naked breasts, the grooved loins

Gleaming like metal with running sweat as they suddenly

Turn, feet apart

And dance and dance, forever dance, with breath half

Sobbing in dark, sweat shining breasts,

And lustrous great tropical eyes unveiled now, gleaming

A kind of laugh,

A naked, gleaming dark laugh, like a secret out in the dark,

And flare of a tropical, tireless, afire in the dark, slim

Limbs and breasts

Perpetual, fire-laughing motion, among the slow shuffle

Of elephants”.

After a gruelling four-month journey in all parts of India it would have been a relief for the Prince of Wales to come for the short visit to Ceylon enroute to Tokyo where he was to be the guest of Prince Hirohito. He had been ill in India but his father King George the fifth, had insisted on his continuing on this mission.

According to the journalists who accompanied the Prince, he was bored by India and his demeanor showed, “as if he was recovering from a drinks party the night before”. Lawrence unerringly picked out Edward’s sense of ennui when he called him “that tired remnant of Royalty up there”. The Perehera had over a hundred elephants. By now the dancers had emancipated themselves from the Kankariya and had turned Ves Natum into the signature dance of “men peasants from jungle villages dancing and running with sweat and laughing. Naked dark men with ornaments on, on their naked arms and their naked breasts.” The taboos of the Kankariya had been broken and the performance was all.

Lawrence caught perfectly the then ambience of colonial British India. The first small cracks in the glass ceiling were beginning to appear. The zenith of British imperialism was seen in the Delhi Durbar organized impeccably by Viceroy Curzon in January 1903 to mark the coronation of King Edward the seventh, the very prince and elephant killer who had visited India and Ceylon in 1875. Since then, Curzon himself became the object of hate of Indian nationalists, particularly the Bengalis who resisted and rolled back his partitioning of Bengal in 1905. The political associations which began in Bengal was widened to give it an all-India representation in 1885. From then on step by step, the anti-British independence movement became more and more radical.

As Patrick French writes, “far from 1919 being the year in which India’s freedom movement was quelled by gentle concessions of the British Parliament, it marked the start of serious agitation. The outspoken tactics of Gandhi appealed to an entirely fresh audience, and Congress was now transformed from the club of India’s civilized elite into a populist political organization” (1997;37). In Ceylon, the young leaders of the national elite began to look to the growing activism led by Gandhi in India and they too sought to strengthen their national identity through new representations based on their ancient religion and culture. The older pro-colonial elite were slowly drifting towards their sunset years.

Kohomba Kankariya, a Vijitha Yapa publication,

is priced at Rs 2,000 and available at leading bookshops.