Playing with boiling oil

View(s):

File picture of a fuel hike protest

Our food is becoming oily again, whether we like it or not. It is not because we keep adding more ‘cooking oil’ to our food, but because of the “rising oil prices” in the world. On average about 20 percent of the cost of food production is said to have originated from fossil fuel. The fuel cost includes the use of oil for producing fertiliser, operating agriculture machinery, processing food in the factory and, transporting it to markets and consumers. All these activities require oil as an essential input. If this is the case, what do you think of food prices ahead of us?

When the world oil prices rise, food prices should rise too. Here we are facing the rising oil prices again so that we should anticipate an increase in food prices as well. Anyway, before we come to that point, I must say that the above is not the whole story. It is not because oil is important for agriculture, but the fact that agriculture is important for oil. Let me explain.

Agriculture for oil

About 15 years ago, world oil prices were rising steadily; it was US$30 a barrel by the end of 2001 and, gradually rose to over $170 by mid-2008 – an increase by over 460 percent in six and a half years! Why did oil prices start to rise so sharply?

Apart from the usual trends causing demand-supply imbalances, it was the time that the world was preparing for the forthcoming global financial crisis. Some of you might say that the world didn’t know that there was a crisis coming in. It was not unexpected; investors in currency markets, bond markets and stock markets already knew about it. I heard about it as early as 2005 and, together with me there were many Sri Lankans who studied it at a lecture at the University of Colombo.

What do you do, when there is an early warning about an impending tsunami? The investors started shifting their investment from financial markets to commodity markets assuming that the latter is considered a haven to protect their wealth. And oil is a commodity (just like gold), as anticipated, could save your money. Thus, instead of stocks and bonds, investments flowed into oil markets causing their demand to rise.

The oil price hike due to its rising demand was followed by a food price hike. During the 5-year period in 2003-2008, average food prices in the world, as measured by the FAO Food Price Index, has more than doubled. The increase in oil prices affecting the cost of production of food was, however, only one factor underlying the rising food prices.

Expensive fossil fuel means higher demand for biofuel. The food price hike was further aggravated by the increasing demand for biofuel, which caused a shift of agricultural land to biofuel land. As The Economist magazine on October 10, 2015 reported, the world’s largest corn producer, the US increased using corn for ethanol production from 6 percent of its corn harvest to 40 percent during the period from 2000-2011.

Oil hedging

In the face of the global financial crisis, oil prices crashed to $60 a barrel in just six months by the beginning of 2009. We also remember the then Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC)’s oil hedging deal. When the oil prices were getting closer to its boiling point in 2007, the CPC entered into a “zero-cost-collar” hedging with a couple of international banks and two domestic banks. Accordingly, if the oil price rises above $130 a barrel, the banks should pay the difference to the CPC and if it falls below $100 a barrel, the CPC should pay the difference to the banks.

Even though the oil prices had crashed in the world market, as per the hedging deal the CPC still had to pay $100 a barrel losing millions of dollars! Finally, it was decided to terminate the hedging deal unilaterally, and the case was taken to international arbitration courts resulting in further losses to the country in millions of dollars.

Even though the oil prices had crashed in the world market, as per the hedging deal the CPC still had to pay $100 a barrel losing millions of dollars! Finally, it was decided to terminate the hedging deal unilaterally, and the case was taken to international arbitration courts resulting in further losses to the country in millions of dollars.

The world economy never recovered from the global financial crisis; it was caught up in the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 and, the crisis deepened. As the demand for oil fell sharply, the world price of oil too fell to below $20 a barrel by April 2020. Although many oil-importing countries including fast-growing China and India, benefitted from lower oil prices during 2008-2020, I am not sure whether it is the case for Sri Lanka. Particularly towards the end of this period, Sri Lanka introduced a fuel price “formula”, which was not a formula per se, abandoned even after a couple of months and reduced fuel prices in September 2019.

Instead of a formula, Sri Lanka introduced a Fuel Price Stabilisation Fund in March 2020 for equalising the costs and benefits of world price variation. The Fund accumulated about Rs. 69 billion under the lower oil prices in the world, while it was utilised to pay part of the CPC’s loans.

Higher food prices again

Now the world is back on an upward oil price track; within about 12 months, the world oil prices have increased to $70 a barrel. As the COVID-19 vaccination is on the move, and the world economy is on a recovery path, the oil demand is on the rise. What do we expect, then? Higher food prices again!

It is not only because oil is needed for agriculture as an essential input, but also because agriculture is needed for biofuel. By the way, a new player in the biofuel market is our big neighbour, India, which has a big plan for increased reliance on biofuel. It has planned to increase ethanol-blended auto fuel from its current usage of 8 percent to 20 percent within five years from 2020-2025 from grain-based and waste-based agriculture land.

According to the FAO Food Price Index, the average world food prices have already increased by almost 40 percent just within the past 12 months by May 2021. The highest increase could be seen in vegetable oils (125 percent) and sugar (57 percent); in addition, the average prices of other food groups have increased too like dairy products (28 percent), cereals (37 percent) and, meat (10 percent).

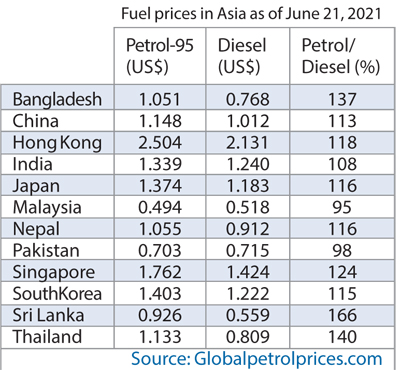

How do we in Sri Lanka manage our domestic oil prices among our neighbouring countries? In this case, there is one thing, which we should be clear about; being a net importer of oil, the Sri Lankan government does not any power and authority to control world oil prices! If it does change domestic fuel prices by a “political will”, we should know that the burden of its manipulation is on the people themselves.

New challenges

Sri Lanka is one of the countries in the region which has the lowest domestic market fuel prices. Moreover, Sri Lanka has been continuing with a significant difference between petrol and diesel prices, through government intervention assuming that petrol is used by the rich and diesel is by the poor. Apart from all that most of the countries in the region allow world market prices to reflect in domestic market prices, whereas in Sri Lanka domestic fuel prices reflect more politics than economics.

As world prices of oil and food are on the rise, Sri Lanka will also have new challenges to face. We cannot forget that in

Sri Lanka, world market price trends are already blended with local issues – both policies and shocks, affecting domestic agriculture, export crops including tea production, and even the fish catch along the western coast!

(The writer is a Professor of Economics at the University of Colombo and can be reached at sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk

and follow on Twitter @SirimalAshoka).