How the Buddha’s Jewel Discourse quelled Indian city’s trilogy of fear

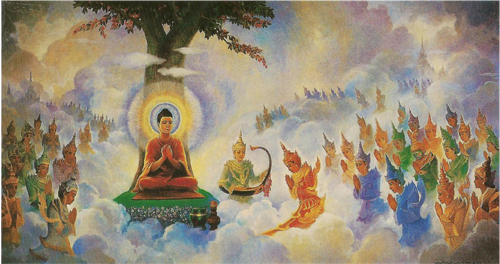

THE THRICE BLESSED DAY OF VESAK: Commemorating the Birth, Enlightenment and Passing Away of Gautama the Buddha

Even as shocking scenes of mass sickness and deaths unfold daily to reveal the full horror of present day India, flashback to 2,500 years ago, when a city in ancient India was harrowed by three waves of famine, contamination and plague; and how the Buddha came to the rescue to give spiritual succour to rid the land of relentless terror.

Some 2,500 years ago in the far off plains of Northern India, the thrice accursed city of Vaishali is writhing in anguish, its people expending their last dying breaths on its wretched streets, their bodies ridden with the pockmarks of disease. From dilapidated houses come the wails of the sick and the dying, imploring with the last ounce of fast dwindling strength for heaven’s succour or for merciful release from a terrible, agonizing existence ‘where hope never comes that come to all.’

This was not the first time disaster had invaded Vaishali, the ancient capital city of the Vajjian Confederacy, a power group of neighouring clans which includes the Licchavis and a major oligarchic republic that existed in the India of old. Today Vaishali is an archaeological site in present-day Bihar, on the site of a village now known as Besarh.

In fact it is the third visitation of the spectre of death in a different guise.

When the grim reaper had first revealed its macabre countenance, it was in the gaunt form of a prolonged famine which took hold of the land and condemned the proud citizens of this once thriving city to hunger and death.

As starvation took its terrible toll, so did the corpses of the dead begin to pile up unattended on deserted streets. They were heaped in by-lanes, flung to be forgotten in dark alleyways, thrown to the wolves in arid nearby fields, dumped in stagnant ponds and left to float, the putrefying bodies oozing the stink of death.

The foul odour given off by the abandoned and rotting carcasses, partly eaten by vermin, partly by vultures, maggots and flies, attracted the unwelcome morbid attention of evil spirits who stalked the land at night in search of dead prey and gorged on decaying human carcasses with relish.

Thus did the second wave, the second coming of calamity strike the land and invite the reaper to revisit Vaishali with his scythe. The influx of evil spirits attracted by the smell of the putrid corpses sent a wave of terror amongst the remaining citizenry. And now with the people brought to the brink of annihilation, the spectre wears the mask of pestilence, to nudge them into the abyss.

The leaders of the community meet in council at that ungodly hour when only famine, ghouls and pestilence – each one silhouetted in the backdrop of death – stare them in the faces; and swiftly decide to seek the succour of the Buddha. They send a messenger to the Enlightened One to make haste to the famine struck, ghoul infested, pestilence ridden Vaishali to save the city’s remaining souls.

It is a journey of approximately 98 miles but having ridden fast and hard into the night, the messenger finally arrives at the great city of Rajagaha by morn where the Buddha is sojourning. It is here in Rajagaha, also known as Rajagrihar, ‘the Royal Household,’ that the Buddha spends many months of the year meditating and preaching at Gridhra-kuta, ‘the Hill of the Vultures’, the park where he had delivered some of his most important of sermons, including, Atanatiya Suthraya and had, also, initiated King Bimbisara to follow the path the Buddhas trod.

It is to this verdant park, the messenger makes his way. But even before the message is handed, the Buddha divines its import. It is from Vaishali, and it contains the piercing wails of a people in pain beseeching him for release.

Vaishali, the land from which the powerful warrior clan of the Licchavis had risen to lay claim to the great Kathmandu valley, was not entirely unknown to the Buddha. Nay, he was quite familiar not only with its terrain and climate but his association with its people went a long way back.

After renouncing his father’s Kingdom of Kapilavastupura, and leaving behind him his tearful wife and newborn son; after flinging to the Fates in disdain the princely pleasures of the royal palace; to lead a frugal lifestyle wrapped in the coarse cloth of the mendicant and embark on an unknown quest on an unknown path for an unknown treasure he knew not existed, it is to Vaishali he first came to receive initial spiritual guidance from sages Ramaputra Udraka and Alara Kalama.

After gaining Enlightenment, he had paid many visits to Vaishali. It had been at Vaishali, he had established the Order of Bhikkhunis, initiating his maternal aunt and foster mother Maha Prajavati Gautami into the order as the first bhikkhuni. In fact he had spent the last rainy season here and in time soon to come, he would leave his alms bowl with the people of Vaishali, before heading to Kusinagara to await Mahaparinirvana.

The Buddha rises from his seat and sets off in the northern direction of Vaishali. A large retinue of monks follow him. By his side is his attendant disciple, the Venerable Ananda. As they reach Vaishali a pall of gloom hangs over the city.

Soon the sky begins to rumble and the clouds surrender their trove of rain. A torrential downpour falls on the thirsty ground thus ending its long drawn drought that had first brought the famine to the land. In the roaring deluge, putrefying corpses dumped on the streets and alleyways are swept away. And the fetid city of Vaishali rises from the sudden outbreak of welcome rain with its squalor gone. With the atmosphere now purified, with the ground now thoroughly cleansed, with the air fit to breathe once more, the city now glistens with sparkling light.

The Buddha then sends for the Venerable Ananda. When the attendant disciple arrives, the Buddha bids him sit and advises him to listen attentively to what he is about to preach. Thereupon the Buddha delivers the Jewel Discourse to the Venerable Ananda. The last sermon he would deliver before his passing away. He then gives him specific instructions as to what must be done. He tells him to tour the entire city with the Licchavi citizens reciting the same Jewel Discourse he had just heard from the Master’s lips. To recite the Jewel Discourse as a talisman of protection to the Vaishali people.

The Venerable Ananda immediately rises to the task the Buddha had charged him with; and he proceeds without delay to discharge his duty in the company of the Licchavi citizenry. Whilst touring every part of the city, reciting the stanzas in the Buddha’s Jewel Discourse repeatedly for it to become a potent mantra of protection against evil forces at large, he simultaneously sprinkles sanctified water held in the Buddha’s own alms bowl, disinfecting every street and every alley, every path and every passage, every nook and every cranny until at last the entire city is sterilized and cleansed.

Only when his repetitive recitation of the Buddha’s Jewel Discourse together with his liberal sprinkling of sanctified water on the city streets and byways have exorcised the evil ghouls and banished them to whence they came; and the awesome power of the pernicious pestilence to bring death wholesale to plague the city of Vaishali had dramatically been quelled, does the monk, Venerable Ananda, with his task done, return with the Vaishali citizens to the city’s main Public Hall where the Buddha, together with his disciples in attendance, await his arrival.

Then do the Vaishali citizenry, their minds purged of the fear of famine, the fear of wandering ghouls, the fear of death bearing viruses, free of the fear of inevitable death, free of fear itself, now calm of mind and robust in spirit, gather before the Buddha and await to hear firsthand what they had earlier heard Venerable Ananda repeatedly reciting whilst touring the city.

Then the Buddha begins to deliver the Jewel Discourse to the assembled gathering, their once nerve wracked minds now unpolluted receptacles to receive the Buddha’s all-encompassing wisdom.

In the Jewel Discourse, after having first placated the evil spirits by the practice of Maithrie or Loving Compassion which constitutes one of the Four Sublime Truths as preached by the Master, the Buddha proceeds to define the three jewels of Buddhism, namely, the Buddha, Dhamma and the Sanga.

To describe the first jewel, the Buddha, explains the qualities present in three verses, in 3, 12 and 13: “Whatever treasure there be either here or in the world beyond, whatever precious jewel there be in the heavenly worlds, there is naught comparable to the Tathagata (the perfect One). This precious jewel is the Buddha.’’

To explain the quality of the Dhamma and what the Dhamma is, the Buddha describes it in two stanzas: Verses 4 and 5 where he says, “That Cessation, that Detachment, that Deathlessness (Nibbana) supreme, the calm and collected Sakyan Sage (the Buddha) had realized. There is naught comparable to this (Nibbana) Dhamma,’’ and verse 5 where he states “The Supreme Buddha extolled a path of purity, the Noble Eightfold Path, calling it the path which unfailingly brings concentration. There is naught comparable to this concentration. This precious jewel is the Dhamma.

But when it comes to explaining the qualities of the third precious jewel of the Sangha and who the Sangha really are, as opposed to the Bhikkhus, he takes 7 verses to exactly describe it. In verses 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 14, he describes them as those who with steadfast mind and due effort have become arahants, and enjoy the peace of Nibbana, as those who have entered the deathless state.

The Jewel Discourse upholds the Three Jewels as follows: the Buddha as the unequalled Realized One; the Dhamma as Nirvana and the Eightfold Path of unsurpassed concentration leading to Nirvana.

And the Noble Community of Sangha as those who have:

attained Nirvana (verses 7: te pattipatta amatam vigayha),

realized the Four Noble Truths (verses 8-9: yo ariyasaccani avecca passati), and

abandoned the first three fetters (verse 10: tayas su dhamma jahita bhavanti) that bind all to samsara.

It makes clear the Sangha are the monks who have followed the path of the Buddha and thus become arahants and are worthy, along with the Buddha and the Dhamma as being a refuge to all Buddhists. Those monks belonging to the Order of Bhikkhus do not fall into this exalted category as they are still not even on the path and become stream winners; but are still mere aspirants yet to step on the first rung sovan.

The last three verses of the Jewel Discourse, namely verses 15, 16 and 17 are held to be recited by the Sakka, the chief of the Gods.

The Buddha’s Jewel Discourse or the Rathane Suthraya has remained one of the most important Suthrayas in the Sutta Pitakaya and has been an enormous influence on the collective conscience of the Sinhala mind. Its potency to offer protection against evil spirits and diseases have contributed to its top billing, only next to the Karaniya metta Suthraya.