A treasure trove of discerning tales of the human psyche

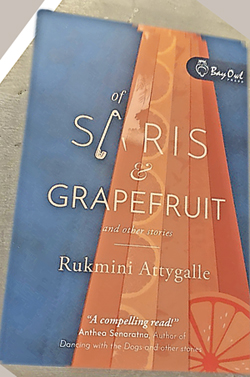

View(s): Rukmini Attygalle has been writing creatively for many years. As she says, she credits others with recognising the worth of her work, and thanks them for encouraging her to publish this, her first collection of short stories. The work comprises eleven stories.

Rukmini Attygalle has been writing creatively for many years. As she says, she credits others with recognising the worth of her work, and thanks them for encouraging her to publish this, her first collection of short stories. The work comprises eleven stories.

As the title implies, inspiration comes from many a source, finding fruition in discerning tales of the human psyche.

Rukmini does not shy away from ‘difficult’ topics. Indeed, suffering plays a major part in many of her stories. Boldly touching upon paedophilia, dementia, or simply ageing, disfigurement, illness and fatal ragging, to name a few of her themes, the writer draws us into these spheres with a very light hand, tells us her story and manages to bring us out of them, uplifted, enlightened, sometimes saddened and sometimes, amused.

This is a commendable result and points to a certain sureness in message; subtlety in presentation and very clear and descriptive language.

It is refreshing to find an author who is willing to experiment with voice and point of view. While many stories are written in the third person, Moneylender, Tussle for Independence, Letdown, among others, are written in the first person.

These stories are strong.

Rukmini’s First Person serves as a perfect foil for the protagonists in her stories. The narrator brings to life her heroines, heroes and antiheroes in a capable and sympathetic manner.

Andoris, the double-jointed mendicant and the knobby kneed Kumi, are my personal favourites, while Andare, who sits on The Shared Bench with Swarna/Mali is a very empathetic character.

“… You were so young and so naïve; you hadn’t learnt the art of hiding your feelings. I, on the other hand, was able to control my yearnings. While you were just passing through a phase of late teenage infatuation, I was actually in love with you!”

She, on the other hand, demonstrates how blind the sighted can be.

“…This revelation proved too much for Swarna to absorb and understand immediately. She gaped at Andaré, speechless. “Remember?” He repeated. She could not respond. She was too shocked to accept the fact, leave alone comprehend the strange circumstance of this coincidental meeting

“Surely you could not have completely forgotten my existence?” He persisted.

“Swarna was confused and lost for words. She could not digest this information that had burst in on her. She could not collate it in order to make sense of the situation.”

Evocative description is another of Rukmini’s strong points.

“The kitchen at Ambagas Hewana was a hive of activity with Latha ruling the roost. She had organised some of the wives of the estate workers to help out. Onions were being chopped for seeni sambal; brinjals fried for batu pahi; vegetables prepared for achcharuu; and kaludodol being stirred in a huge pan. All these for taking to London.”

And from Shadows on the Wall:

“All three of us sisters loved the shadows our father made on the wall with his hands. They were happy shadows. By bending and twisting his wrists and fingers he could make animal shadows. The rabbit shadow he made was my favourite. It could run and hop up and down, shake its paws, wiggle its ears. Thatha taught me how to make the rabbit shadow but my rabbit’s ears would never stick up. They always drooped. The eagle shadow he made would come sweeping down and he made it disappear on the floor. The crocodile shadow was the easiest to make. All you had to do was place your palms together and hold them parallel to the wall and open and close your hands resembling a crocodile opening and closing its mouth.”

In The Setting Sun again using the First Person voice of Suren, Rukmini brings to us the pathos of the life of a fisherman’s widow, two young children one of whom is stricken with cancer and Suren who had to grow up fast once his father died.

“ …Anyway, there was little chance of me loafing around anymore. I hardly ever met the old gang on the beach since Thatha’s death. I had more important things to do now. I’m glad I learned to mend fishing nets from Thatha. After school, in the afternoons, I often helped other fishermen – especially old Nomis Mama – mend their nets. I earned a few rupees, for which Amma was grateful. When the catch was hauled in, they would give me a handful of sprats or small salayas …”

However, it is her masterly presentation of Wimal, which stands out. He dominates the story although she gives him very little time on the page. Anti- hero or first victim? All this is left to the reader to decide.

Rukmini’s stories are presented with realism. This seems to be her preferred form of narrative. Plots are simple and the themes straightforward. These bear touching upon again.

In addition to those mentioned above those of death, and conflict in war, and personal conflicts within the conflict of war are very delicately drawn.

In Brilliant Bougainvillea, the mother of the injured soldier,

“…heard him whisper to himself, panati-pataveramanisikka padam samadiyami mouthing the precept to abstain from killing… “

We are made to ponder the conundrum of war and the conflict within each self.

In The Dawn of Death, we experience again, the struggle in the war-torn Wanni. The war is “over”, but stories like this still serve to jog our conscience and our consciousness of suffering everywhere.

In conclusion, I return to my favourite knobby-kneed heroine and her no less heroic mother. Having granted her little one some freedom, she, the mother, admits,

“… I found myself running to the porch every few minutes to see whether Kumi was walking up the hill. About twenty minutes later, to my great relief, I saw the pair of skinny legs with knobby knees trudging up …”

Kumi, demonstrating that she was indeed worthy of her new independence, thanks her mother with a gift.

“It’s the nicest present I have ever received,” says Kumi’s relieved mother. And muses,

“… What Kumi did not realise was that she had given me a flower that would never fade; for it is still fresh in my memory and reminds me of the day it was presented to me with stick-like outstretched arms, a beaming face and a wide grin…”

This reviewer too, with a pleased grin, opts to leave the reader to discover the rest of the treasure in this trove Of Saris and Grapefruit.

| Book Facts | |

| Of Saris and Grapefruit By Rukmini Attygalle Reviewed by MTL Ebell |