News

“Bugger off my land,” said ex-SAS soldier turned KMS worker; dies aged 86

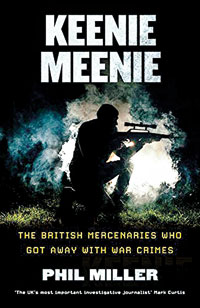

Reproduced below are excerpts of an article on the KMS’ involvement in Sri Lanka during the early years of the war. The article by Phil Miller, author of ‘Keenie Meenie: The British Mercenaries Who Got Away With War Crimes’ was published in the Declassified UK website.

On a warm day in late spring 2018, a sleepy village in the English countryside was about to be disturbed by my team of investigative journalists. We were poised to interview Lieutenant Colonel Brian Baty, a reclusive former mercenary who we had tracked down to the village of Kings Pyon, a stone’s throw from the Special Air Service (SAS) base at Credenhill, Herefordshire.

His house was easily distinguished by a towering flagpole with a Union Jack fluttering on the front lawn, and a car with his personalised number plate parked on the driveway. My two colleagues started filming as I approached his front door and began to knock. At first there was no response, until an upstairs window swung open.

Baty serving in Malaya. (Credit: British Army)

“Hello”, I called out as Baty, a well-built man in his eighties, appeared. “Yes and you can bugger off!”, he shouted down at me, before I had a chance to introduce myself. “Are you Lieutenant Colonel Baty?” I countered, trying to sound calm. “You can bugger off,” he repeated, irate.

I persisted and tried to question him about his time working for a British company, Keenie Meenie Services (KMS), about which I had written to him previously and received no response. “These are very serious allegations sir… You’re being linked to war crimes in Sri Lanka,” I reminded him. “Bugger off my land, get out!” Baty shrieked back.

As Baty withdrew from the window muttering abuse at me, I asked: “Do you deny that KMS was involved in war crimes in Sri Lanka, under your watch?” There was no response. Baty could not deny it, he could only hope the issue would go away. Instead, it would follow him to the grave.

After 33 years of service, Baty left the British army in October 1984, aged 51, as a Lieutenant Colonel. He had risen impressively through the ranks, however he had made plenty of enemies. On Christmas Eve 1984 — just two months after he retired — the Special Branch of the British police arrested Peter Jordan, an Irish Republican sympathiser who had been plotting to blow up Baty.

Baty’s secret war in Sri Lanka

Baty’s secret war in Sri Lanka

Amid this turbulence, and perhaps because of it, Baty left the country. He began working for one of Britain’s most powerful private armies, Keenie Meenie Services (KMS), which is thought to be named after Arabic or Swahili slang for undercover activities.

Although the Telegraph newspaper compressed this part of Baty’s career to a single line in their glowing obituary of him, it was one of the darkest episodes in the violent world of British mercenaries.

KMS was run by well connected ex-SAS commanders who were paid handsomely to run the Sultan of Oman’s special forces, as well as helping US marine colonel Oliver North to overthrow a democratically elected left-wing government in Nicaragua.

Baty’s decades of counter-insurgency experience in Ireland, Oman, Yemen and Malaysia made him the prime candidate to lead a KMS team on another of the company’s major contracts.

Sri Lanka’s ruling Sinhalese majority urgently needed military support from KMS to suppress an armed separatist movement among its marginalised Tamil minority. (Margaret) Thatcher’s government had refused to intervene directly, fearing it might sour UK trade deals with India, which initially supported the Tamils.

One of Thatcher’s special advisers had suggested that “this venture might be privatised” and soon after, KMS began its work in Sri Lanka in January 1984.

Their first task had been to set up and train a Sri Lankan police commando unit, the Special Task Force (STF) at a military academy south of Colombo in Katukurunda, that was modelled on the SAS base in Herefordshire. By January 1985, Baty had started working for KMS from a base in the Sri Lankan capital of Colombo, where he used the alias Ken Whyte. Local Sri Lankan security chiefs told my team that they believed this “nom de guerre” would hide Baty’s whereabouts from the IRA.

Owing to his senior position at the head of the KMS team, Baty was installed in an office next to Sri Lanka’s National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali and had “direct access” to this leading politician.

Baty’s arrival, with his considerable experience of training SAS recruits, allowed KMS to expand its footprint in Sri Lanka and begin training a new army commando unit, in addition to the police STF. By March 1985, Baty appears to have been “acting effectively as the Director of Military Operations of the Sri Lankan High Command,” according to a declassified UK government telegram.

Crucially, they noted that the STF was operating in unmarked cars and wearing plain clothes. This description suggests that elements of the police commando unit were operating undercover, as Baty had trained scores of British troops to do at Pontrilas before he joined KMS.

Many of these details about Batys time in Sri Lanka were recorded by the defence attaché at the British High Commission, Lt Col Richard Holworthy. The pair held regular discreet meetings to keep the UK Foreign Office completely up-to-date on what KMS is doing. These meetings were minuted afterwards by Holworthy, whom I have interviewed, and many of the documents he wrote are available to view at the UK National Archives. Although Baty had used the cover name Ken Whyte throughout his time in Sri Lanka, his role there was partially disclosed as far back as 1993 in a book by Stephen Dorril.

However, there has never been a UK government investigation into Baty’s command level responsibility in Sri Lanka — or even his position as an accessory.

Despite years of official obstruction, in January 2020, I published my book, Keenie Meenie: The British Mercenaries Who Got Away With War Crimes, which laid bare the extent of Baty’s misdeeds in Sri Lanka. It caught the attention of the Daily Mail, who referred to the allegations against Baty by name in a review of my book in late-January.