A happy marriage of Kandyan and Baroque

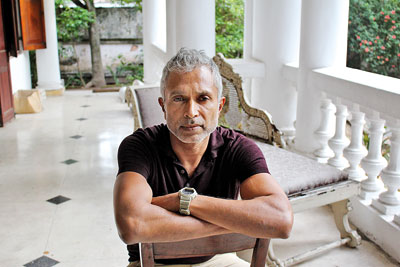

Suresh Mudannayake

No. 12 Flower Road was how Suresh Mudannayake, a.k.a. Ashok Ferrey, re-imagined a Kandyan townhouse of the 17th Century. It’s proof of the little-tapped potential of Suresh the polymath, better known for his writing. Those classy but quirky architectural sketches with which this flamboyant wit fills his short stories and novels spring to life in No. 12 which is home, currently, to the Cricket Club Café.

This townhouse/café blends medieval Kandyan architecture with the Baroque- which in the 17th century was still fashionable in Europe and hitchhiked to Ceylon with the Portuguese. Although worlds apart, “their marriage I think was a happy one,” says Suresh, given that the two traditions have uncanny similarities.

The roofs and spires of No. 12 are classic Kandyan but ornate roofs with spires, cupolas and obelisks are parts of a typical Baroque house also. While we would like to think of the curvy windows and wooden panels above No. 12’s doors and windows as Kandyan they were actually Baroque legacies to our 17th Century Kandyan temples, points out Suresh.

The building has character born of Suresh’s vivid historical imagination and cosmopolitan chic in its mélange of east and west in the façade. Basically built around a central courtyard, a series of rooms spiral upwards.

A wonderful touch are the turquoise wooden columns and railings. Some of the columns, windows and doors come from Suresh’s mother’s house in Moratuwa originally built in the 17th Century. This was where the great heiress Lady Catherine de Soysa was born in 1845 while being connected to many other Moratuwa families who originally thrived on arrack renting. “You can’t imagine how delighted I am that the current house has ended up where that story began all those years back – as a place where they serve the finest arrack cocktails!”

A view of the interior and (right) curvy lines of a baroque window. Pix by Seneka Abeyratne

Within, especially in the open courtyard, Suresh has managed to conjure a convivial, relaxed, spacious atmosphere which turns mellower as day wends to evening. “I have tried to make the building feel as if it is someone’s slightly-down-at-heel private villa, where they have hauled the grandmother down from the attic, grumbling, to do a little light cooking, a place where you instantly feel relaxed because it is not too precious or ‘up its own backside’, as so many restored colonial buildings can be.”

The house is all exposed brick and peeling wood. Suresh says the weathered, seasoned look is very important to him because in the tropics a shiny, brand-new house will succeed in looking shabby after just two monsoons. It is often far better to embrace the fierce weather, factoring it into the design. The house also employs a minimum of concrete, because concrete rots quickly in the tropics, and is then hugely expensive to demolish and replace.

One of the major challenges was to persuade the baases that the brick arches of the loggia would not fall down. They were so used to concrete that even Suresh’s assurance that the Colosseum in Rome survived on brick arches for 2000 years drew looks of disbelief.

Another challenge was to minimize noise, given the busy Flower Road frontage. Suresh ended up placing all the bathrooms, kitchens and service in the front façade, which is one room thick, and placing the reception rooms and principal bedroom at the back of the courtyard.

Another challenge was to minimize noise, given the busy Flower Road frontage. Suresh ended up placing all the bathrooms, kitchens and service in the front façade, which is one room thick, and placing the reception rooms and principal bedroom at the back of the courtyard.

The other massive challenge was money. But Suresh says nothing concentrates the mind better than the lack of it: many extravagances you think necessary at the time are found, years later, to have been no more than a vulgar ‘ego trip’, adding nothing of real value to your creation.

In Suresh’s case it took 20 long years to collect the funds; during which time he bought 40,000 colonial bricks from a demolition site across the road (at a rupee a brick), cut down a 50-year-old margosa tree in the garden for flooring (having pre.viously planted three others to take its place), and amassed a quantity of old h-irons. So when it came to the construction he was armed and ready- and the work done in nine months.

For Suresh, the worst that you can do to your building is to over-think it, making it too neat and sterile. Something should be left to the imagination of the person walking through the spaces keeping things unfinished and open-ended.

Though the Geoffrey Bawa Award is now in its fifth cycle, Suresh remains only the second non-architect to have ever been nominated. He says he is “over the moon to be listed among these amazingly talented architects”.

“If this is as far as it goes, it is certainly good enough for me!” he says. “One of the judges, Barry Bergdoll, is part of the Pritzker Prize Jury (the Oscars of the architectural world). This makes the validation hugely gratifying – particularly to a small-time builder like myself.”

Meanwhile, Suresh is busy with his next project: reworking a very aristocratic Kandyan walawwa which he has already made into a literary star having cast it as the main character in his 2016 novel, The Ceaseless Chatter of Demons.