What’s in a name? Everything when it’s ‘The Beatles’

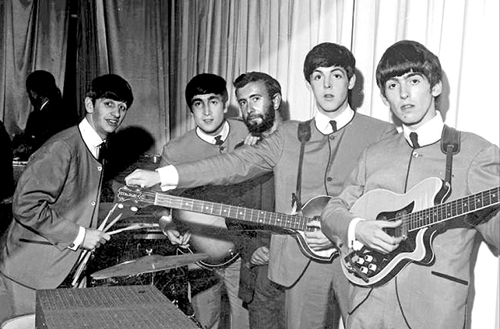

The Fab Four with Royston Ellis (centre) in 1963

Sixty years ago the man behind the name change of ‘Silver Beetles’, a little known British pop group then was none other than Royston Ellis, a celebrity of the youthful Beat Generation who has long since

made Sri Lanka his home

Liverpool, at the start of a brand-new decade. There is a beat in the air, there are beat groups, too; soon there will be a sound christened Merseybeat and not long after a weekly newspaper called Mersey Beat to record this crackling creative scene. But in the city, in the spring of 1960, there were, as yet, no Beatles, only a five-piece act called the Silver Beetles, heirs to a skiffle group named the Quarrymen.

However, in June of that year, the hard-working but struggling combo, just one of hundreds of such groups in a port of imported rock’n’roll, thriving docks and transatlantic liners, would assume the name to carry them to national and international superstardom. The Beetles, during that auspicious early summer exactly 60 years ago, would become the Beatles, a calling card to the world. What prompted this small but significant transformation?

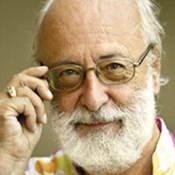

Royston Ellis: Domiciled in Sri Lanka for over 20 years

The youthful Svengali at the heart of this newly-minted identity was a remarkable young man called Royston Ellis, a performer described as a Beat poet, a rare British incarnation at a time of Angry Young Men and kitchen sink plays and novels. But Ellis was a most unusual English example of an American literary style that had set alight headlines in New York and San Francisco in the years between 1955 and 1959, delivered by a group of writers and friends dubbed the Beat Generation.

In the USA, poet Allen Ginsberg had read and then published a tumultuous long verse called ‘Howl’. By 1957, this excoriating vision of a powerful yet paranoid land – economically prosperous but living under the shadow of nuclear threat in an age of Cold War – had become the focus of an obscenity trial, its extraordinary fusion of sex and politics, jazz and drugs, a simmering threat to the sensitive WASP sensibilities of mid-century America.

That same year, a brilliant and radical novel called On the Road by Jack Kerouac, in which journeys on the highways of North America became metaphors for a personal quest for freedom and self-identity, hit American bookshops and the bestseller lists. The book distilled an essence of excitement and energy for its young readership: love and kicks on Route 66, thrills and spills from the cities to the hills, coast-to-coast adventures set to a fast and furious bop soundtrack, a westward search for a grail both holy and unholy. It became the Bible of a new hipster vision.

Two years later, the strangest of these explosive fictional voices was framed in William Burroughs’ sensationally experimental Naked Lunch, a disturbing and sometimes distressing portrait of a drug induced dystopia, in which the author made his powerful case against the prim conventions of quotidian life.

Back in Britain, Royston Ellis was a 20-year-old with aspirations of his own, a tender-aged poet who began to gain exposure through his readings with a freshfaced community of US-influenced but Anglo-nuanced musicians. He appeared on UK TV reading his verse with Cliff Richard’s Shadows and, whether on stage or the small screen, Ellis happily accepted his nomination as a British Beat.

Soon he was on tour and appearing live at various pop music venues, which was how, in 1960, he came across John Lennon, Paul McCartney and co in their home city. He was a celebrity of the youthful pop scene; they were essentially unknown, barely even local heroes of this time.

Ellis visited Gambier Terrace in the heart of Liverpool, a handsome but faded Georgian block in a declining area of the city, where Lennon lived with his friend Stuart Sutcliffe and others of their art school associates. The poet hit it off with this musical crowd and stayed for several days.

When he asked them about their band name, he enquired where they had sourced it. Lennon explained that it was a reference to the nickname for the popular Volkswagen vehicle. There were other hints that Buddy Holly’s Crickets had also been a related reason for the choice.

Ellis proposed that they might make a smart and hip amendment and subtly reference the American subcultural underground by switching the spelling to BEATles. The group’s de facto leader concurred and the rest is a history beyond histories.

Yet this story of smoke-filled bohemias – flats and bars and clubs – has other twists and shouts. Lennon, Sutcliffe and their pal Bill Harry, who would soon launch and edit the publication Mersey Beat in 1961, had already shown an interest in the Beat Generation writers as early as 1958.

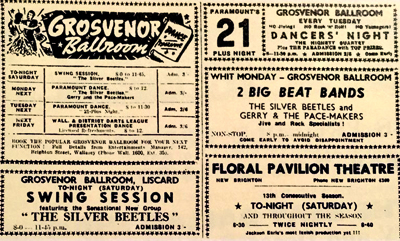

The way they were: The Grosvenor Ballroom advertising the Silver Beetles. They changed their name half-way through the residency

The controversial ‘Howl’ trial, which eventually declared the poem was not obscene but possessed artistic value, had garnered newspaper column inches over in the UK, too. Lennon, who was specialising in calligraphy at the city’s famed art school, had previously published a humorous comic with the title The Daily Howl while at school in 1955, but this was more coincidence, a case of Zeitgeist, perhaps. More pertinently, On the Road had been published in Britain the year after its US debut and the student trio would discuss such Beat topics in the hustling, bustling pubs around their college, at bars like the legendary Ye Cracke and The Philharmonic. So Lennon did not require a great deal of arm-twisting to follow Ellis’ tip when it came to adjusting his group’s name to accommodate reference to those admired Beat writers.

Steve Turner, who wrote a celebrated 1995 biography of Kerouac, Angelheaded Hipster, quoted the story of the name switch and also Bill Harry on Lennon: ‘He loved the idea of open roads and travelling. We were always talking about this Beat Generation thing.’

Fast forward: in spring 2020, Jerry Cimino, director of the Beat Museum In San Francisco, and I had a conversation emerging out of the then widening lockdown, as the coronavirus pandemic spread across the globe. The museum was closed, my own live dates with a Beat theme had been postponed, and the two of us had a Skype chat about projects we were trying to develop in the wake of the new restrictions.

The imminent anniversary of the re-christening of the Fab Four as the Beatles cropped up. The story of poet Ellis and his Beat prompt to Lennon had fascinated both of us for many years. Cimino’s curatorship of the long-running institution celebrating the Beat writers and my own keen interest as a writer in that fertile intersection between those US novelists and the culture of Anglo-American rock from the mid-1960s, gave us both an enthusiasm to re-visit this seminal story in that long-ago Liverpool.

It did not take long to re-connect with Ellis himself. Close to six decades on from his inspired re-branding of the century’s most famous band, he remains an active writer, domiciled in Sri Lanka, that exotic South Asian island off the coast of India. It’s been his home for many years and he has led quite a few different lives since his brief flame of fame as pop poet at the cusp of the monochrome Fifties and the Technicolor Sixties.

The Silver Beetles changed their name to The Beatles midway through a 13-week residency at the Grosvenor Ballroom, sometime between June 5th and June 11th.

There is another relevant story, too, linked to the name change which appears to verify Ellis’ own memory. As Jerry Cimino himself relates: ‘During my own research I’ve found Yoko Ono has been quoted a number of times how John Lennon “had a vision” that he personally shared with her.’

Lennon had told her that ‘The man with the flaming pie said unto me you will now be known as Beatles with an “a”.’ Cimino explains: ‘Ellis claims one time when he went to John and Stu Sutcliffe’s flat he brought a chicken pot pie – and it caught on fire! And decades later Paul McCartney released a 1997 solo album called Flaming Pie.’

However, for Royston Ellis, in many ways, the Beats are an intriguing detail wrapped in the mists of another time. He has gone on to be a successful writer internationally over many, many years – novels, poetry, travel books and more – and his fortuitous meetings with musicians who would later rule the planet are just fragments of memory.

But for fans of the group and for followers of the Beat Generation, his linkup with Lennon and his friends back in 1960 was a crucial moment in sealing a lasting connection between the divergent worlds of rock’n’roll and literature in the re-spelling of that resonant, indeed legendary, name: the Beatles.

( Courtesy –The Beat Museum,

San Francisco -https://www.kerouac.com/beetles-to-beatles-simon-warner/)