Sunday Times 2

Education: A reverse journey of reflection on the path we missed

No one can deny Sri Lanka’s education has been on a downslide since the early days of Independence when our country was regarded as the success story of South East Asia. C.W.W. Kananngara, generally regarded as the Father of Free Education, was Minister of Education in the Legislative Council, while we were still under British rule. The Free Education Bill was passed at that time.

No one can deny Sri Lanka’s education has been on a downslide since the early days of Independence when our country was regarded as the success story of South East Asia. C.W.W. Kananngara, generally regarded as the Father of Free Education, was Minister of Education in the Legislative Council, while we were still under British rule. The Free Education Bill was passed at that time.

Major Eddie Nugawela was Minister of Education under the first National Government and those of us who remember the charming and gentlemanly Minister observe with dismay the deterioration in the quality of persons who have held this important office since then. The downslide began almost from the start. Sarath Amunugama and Lalith Kotelawela tried to halt it but by then the deterioration was well on its way. There were piecemeal projects of course, but soon there was no checking the outright folly of those who held this supremely important office and interpreted the original Free Education Bill to suit the political times.

This article is going to be one of personal reminiscing. I am probably one of the few persons still living who actually gained a very close and personal view of the private discussions among the leading principals in Colombo. This occurred because I happened to be with my mother (Deshabandu Clara Motwani) at times of these unofficial meetings and it was easier to have me tag along rather than her driving me home. I was given a book to read and told to shut up, after which the principals all forgot about me. I should have been bored out my mind but I had this unexpectedly fascinating front row seat in their deliberations. It is in hindsight that I realise I was privy to the principals’ private thoughts which probably were rarely voiced in public.

My book was ignored. I heard, listened and absorbed. We still had a British Head (Dr. H.W. Howes) in the Department of Education and he tried desperately to fall in line with national aspirations while making his own efforts to prevent certain aspects he saw as being potentially disastrous. I know this because Dr. Howes lived a few doors away from us and he often dropped in to discuss his problems with both my parents. D.S. Senanayake talked to my mother personally but unofficially and principals of private schools were not really given much voice in the new scheme of things.

My book was ignored. I heard, listened and absorbed. We still had a British Head (Dr. H.W. Howes) in the Department of Education and he tried desperately to fall in line with national aspirations while making his own efforts to prevent certain aspects he saw as being potentially disastrous. I know this because Dr. Howes lived a few doors away from us and he often dropped in to discuss his problems with both my parents. D.S. Senanayake talked to my mother personally but unofficially and principals of private schools were not really given much voice in the new scheme of things.

In retrospect, I wonder if this exclusion was because so many of them were foreigners and the new Government might have wrongly thought they were not sympathetic to the nationalistic fervour of the time. Here are a few names of those principals whose unofficial discussions I heard – or rather overheard!

Sister Gabriel of Bishop’s was English, Miss Simon of Ladies’ was Australian, Mrs Pulimood of Visakha was Indian, my mother was American and the heads of the many denominational schools all over the island were foreign. Actually none of them gave the impression of being anti-national although they may have questioned the language policy. I know that my mother and Mrs. Pulimood felt that, like India, we should proceed slowly. Obviously they were right. India proceeded slowly and the English standard in India has risen without lessening the Indians’ patriotism and love of country, while in Sri Lanka the less said about the level of English the better.

The vexatious problem facing the principals of private schools all over the island was whether their schools should join the Government Free Education Scheme or not. It was a troublesome time. It was an option for some schools. Not all.

Certain schools had a choice depending on their status at the time of Independence. This varied greatly. Government schools had no choice of course. They did exactly what the Department of Education directed. Some private schools were already getting a comfortable grant from the Government although they were still fee-levying. Such schools were expected to join the scheme. If they did not do so, they were prohibited from charging fees at all although they could opt to remain private. Others were managing their finances without much Government help. They had a choice one way or another. Complicated wasn’t it!

Schools like Ladies’, Bishop’s, St. Thomas’, Musaeus, St Bridget’s, St. Joseph’s, and all schools that are private today had an unfettered choice as they had been more or less independent of Government aid. They were allowed to remain private and fee-levying if they wished.

H.W. Howes

My mother was principal of Musaeus. At her urging the Board of Musaeus kept the school out of the Free Education scheme. She felt that standards could be better maintained if the school could afford to remain private. Time has borne out her foresight. Musaeus is today’s foremost Buddhist Girls School – private or otherwise.

It was a time of famous, names in the world of education….Father Peter Pillai of St. Joseph’s, Warden de Saram of S. Thomas’, Gladys Loos of Methodist, Miss Simon of Ladies’, Mr. Mettananda of Ananda, Mrs Pulimood of Visakha, Sister Gabriel of Bishop’s, Rev. Mother of St Bridget’s, my mother of Musaeus and principals of outstation schools like Miss Barker of Vembadi, Mrs Samarasinghe of Hillwood, principals of Trinity and Kingswood. They were excellent schools which had operated for years but the choice of opening up was not always popular.

P.de S. Kularatne, Ananda College’s best known principal, had just retired but he had a big say in the Department of Education’s various committees. As a personal friend, he tried to change my mother’s desire to keep Musaeus private. The frantic desire to get into a Colombo school was not necessary then. Today’s confused policies are an amalgamated product of a long line of equally confused ministers.

A little history… Dr. N.M. Perera in 1944 wrote a scathing criticism of parts of the Free Education scheme from Bogambara Prison where he was incarcerated at the time. J.E. Jayasuriya later totally supported his opinion. Sir Ivor Jennings and Canon R.S. de Saram confirmed that Free higher Education was a last minute entry into a Government Report (1945) that took 88 meetings to finalise!

Principals’ meetings were held officially and unofficially and I remember so clearly the dismay with which the idea of Free Education with no pay-back scheme in mind at university level was greeted by the principals. It was almost unanimously opposed by them on the grounds that as a still developing country Sri Lanka could not afford it. The Government was under no obligation to heed them so naturally they felt that a statesman like clarity was missing in final decisions.

Clara Motwani

In answer to the prophesied prohibitive cost, Sir Susantha de Fonseka laughingly told my mother, “Mrs. Motwani, we have so much money we don’t know what to do with it.” Where have those Croesus-like hoards gone now?

“Even affluent countries do not educate graduates free,” warned this collective group but no one listened. Ergo, the principals watched these un-thought out changes in puzzled wonderment. They did not quite know how to deal with the folly of syllabus planners at that time. In any case their opinions were not taken too seriously by those formulating new policies. Decisions were often politically slanted and history has shown us that the universities have proved to be one of the most troublesome problems of subsequent governments. The Cassandra-like cries of those older principals went disregarded although, to be fair, the Government probably meant well. It was all so new after all. Sadly the whole question of higher education was embattled from the start.

On a personal note let me relate what I personally remember about these educationists who knew what they were talking about and were not swayed easily.

The division of students into arts and science classes from Grade 9 upward was not popular. Mrs. Pulimood, a published Botanist, felt that arts students should study some science and vice versa. My mother objected to religion being made compulsory for an Ordinary Level pass. Being American she had a secular approach to it being taught in schools. Sister Gabriel of Bishop’s hoped English would retain its importance. Mr. L.H. Mettananda was approving of the place given to Sinhala and Tamil languages, Warden de Saram felt Latin should be compulsory for students studying medicine….and so it went. Each principal had some sort of pet idea but to the best of my knowledge none of their suggestions was accepted.

One evening mother had a meeting at St. Joseph’s with Fr. Peter Pillai. She found him doing the school timetables. He sat at a table with three teachers and as he was able to keep the timetables in his head he simply told each helper what to put down on the paper in front of him. Computers were not heard of. Father Peter Pillai did not need them. His mind was a computer in itself. They talked about ways to prevent disunity by the enforced division of their pupils by language and religion. “It will be regretted,” was the common feeling but no one dared fly in the face of the Sinhala nationalists. Publicly there were few dissenting voices. On our way home after their discussion, which was carried on without Father missing a beat in his timetable doings, Mother said to me, “You have just seen a genius at work.”

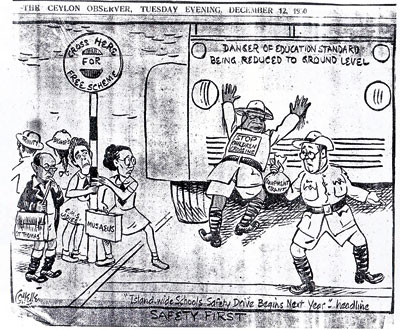

The cartoonist, Aubrey Collette, had a field day portraying these principals dithering around. I give two of those cartoons — one which shows Dr. Howes holding the money bags while principals of Musaeus, Bishop’s, Trinity, Ananda , S. Thomas’ etc stand undecidedly at a bus stop with a bus being held back by Minister Nugawela. The bus stop sign reads, “Cross here for Free Scheme.”

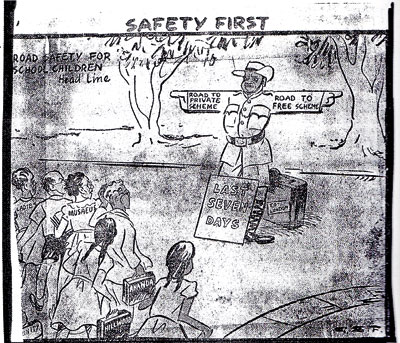

The other one shows the Minister holding out two signs saying ‘Road to Private Scheme” and “Road to Free Scheme” A sign in front of him says, “Last Seven Days.” Collette named each school in the cartoons and tried to make the principals as lifelike as possible in his drawings.

One wonders what would have happened if certain aspects of the Free Education Scheme had been differently applied. A few politically attractive and chauvinistic notions of that time have proved oddly undermining in the light of modern globally oriented education.

We are a nation of believers in astrology. What the stars foretold for us long ago has not been recorded. And this is all to the good, for as we look forward with hope to a new era we should remember the well known Latin axiom, ‘The stars incline us, they do not bind us’. Our future is in our hands.