The Dutch came bearing the Kandyan Royal throne!

The throne as seen today in the museum, the precious stones now replaced by cheap crystals. Pic by Sameera Weerasekera

An intriguing record substantiated by the Archivist Edmund Reimers at the behest of the Director of the National Museum Joseph Pearson in 1929 was unearthed among the old documents in the National Archives.

It is irrefutable proof that the throne of the King of Kandy which occupies pride of place and historical status in our national heritage was none other than a gift from the Dutch Administration in Colombo.

In the Dutch Council Proceedings of October 1692, reference is made to articles collected as gifts for the King of Kandy on the orders of Thomas van Rhee, Governor of the Dutch territories from 1692-1697:

“The question of sending the gifts lying in the warehouse here for the King of Kandy having been resumed it was resolved to select such of them as may make up a regalia for His Majesty, as those noted below.

“Throne with accessories, all the gilt leather (in the warehouse), 2 Chamber screens, 3 Carpets, 1 Clock, 8 pieces of lace for cravats, 45 pieces of white lace, one piece of old lace, four pieces of Surat cloth, four pieces of Dutch material with gold and silver flowers and stripe, 1000 assorted bells….”

Although shrouded in mystery and lacking valid information, Joseph Pearson, was the first historian to enquire into the origins of the Kandyan Throne.

He argued that this royal furniture was a hybrid design an amalgamation of Sri Lankan, Indian and European design motifs.

“The origin of the Kandyan Throne appears to be unknown. I suggest it was made by the Dutch or French prisoners in Kandy and was decorated by the Kandyans or that it was made by the Dutch in the Low country and decorated by Low country Sinhalese and presented to the King of Kandy. The elaborate carving in which the acanthus ornament is abundantly used is Sinhalese.

“The Throne is an interesting adaptation of a European design to conform to the Eastern conceptions’ basic style is undoubtedly Louis XIV but the decorative motif is Eastern. The French influence is not surprising as the Dutch furniture craft at the end of the seventeenth century becomes profoundly influenced by French designs and ideas”.

In 1692 when the throne arrived at the Kandyan Court, the ruling monarch was King Wimala Dharma Surya who reigned for 22 years. Every Dutch Embassy (there were 90 of them) carried with them exotic gifts elaborately packed. Enormous sums were set aside from the Dutch Governor’s budget -as much as 20,000 guilders for this task.

However fragile these gifts were, they were securely packed and transported from Colombo as much as 85 miles to Kandy along rough terrain, winding paths, infested with animals, mostly through hostile territory.

The list makes fascinating reading.

Porcelain from China, jars with nutmeg, sugar candy, rose water from Persia, sandalwood from Timor; wigs specially requested by the King imported from Holland, tigers from Bengal, Indian falcons, sparrow hawks and other exotic birds, horses, and camels from Arabia, African lions, English greyhounds, guns, saddlery, and a whole lot more. Even a small boat for sailing on rivers. One such gift which was much delayed- an African lion that was to be presented to the King – took ill and died and its keeper was imprisoned, living out his last years in the King’s territory.

Regardless -whether Dutch or British, ambassadors risked their life and limb getting there. In the 17th century it was customary that Dutch ambassadors would often deposit their final wills, anticipating death, injury or being detained forever on the King’s orders. One in every ten envoys was taken hostage never to return to Colombo and often lived out their years in isolation in remote villages in the Kandyan highlands.

Within five miles of the King’s territory, all visitors would have to dismount from their palanquins and walk the rest of the way. At Gannoruwa, not far from the King’s Palace the retinue would await permission to enter the city. All activities related to the Audience Hall were conducted at midnight or in the early hours of the morning. At the Audience Hall, the rituals became even more elaborate. The envoy and his entourage would be subject to strict etiquette governed by age-old rituals. To reach the throne room there were nine successive rooms, each space separated with heavy curtains which were drawn one at a time. After a three to four-hour slow progress the visitors would arrive at last in the Audience Hall. Their relief was momentary – while in the presence of Royalty, all visitors would remain kneeling.

All letters, dispatches from the Governor’s Council in Colombo were placed on a heavy silver tray held above the head and the envoy would propel himself forward on his knees towards the King’s throne. Although the Dutch Council, in Colombo remonstrated about such degrading procedures, the Court ignored such pleas.

Almost half a century later in 1736, Wolfgang Heydt, clerk and draughtsman to Ambassador Agreen recorded the audience with King Narendrasinghe: both as a text as well as an engraving, “This now was the place where the king sat on his throne which is found in the palace as it appears within.” From 1692, when the throne first arrived up till February 1815 when the British looted the throne and regalia (almost a century and quarter), Kandy was ruled by six sovereigns.

British records

It is only in the latter half of the 18th century observations of the Kandyan throne are available from records based on four British envoys from the Madras Administration.

By the mid-18th century, when the Dutch influence in the Court had declined the British took advantage of the situation seeking concessions in trade for spices, elephants, arecanuts and other articles. With Ceylon emerging as a staging post to control the Indian Ocean sailing routes, they felt the need to annex the island.

Between 1762 and 1800, the British had dispatched five embassies to Kandy ignoring Dutch threats, crossing the extensive Maritime territories held by the Hollanders who well aware of such dealings behind their backs were quite confident that nothing would come of such efforts.

The delegations sailing from Madras (Chennai) would make landfall in or near Trincomalee, make their way to Mutur, Dambulla, Gannoruwa and then into Kandy Town. In 1762, John Pybus from the British East India Company set off from Trincomalee on May 5, arriving in Kandy by the 18th. He gives interesting details regarding the state of the island, an exhaustive account of court etiquette and the throne – “Seated on a throne, which was a large chair handsomely carved and gilt raised about three feet from the floor.”

Twenty years later in 1782, Hugh Boyd, Private Secretary to Governor McCartney offered an audience with King Rajadhi Rajasinghe, and noted “a very high throne”.

In September 29, 1795, Robert Andrews of the Madras Civil Service, who was received by Rajadhi Rajasinghe on two occasions described it thus; “…seated on a throne of solid gold richly studded with precious stones of various colours”.

Rajadhi Rajasinghe wanted the Dutch ousted, and so entertained many British Ambassadors. On August 11, 1796, Lieutenant Dennis Mahoney recorded that the English Ambassador was received by the King – “seated on his throne in all the pomp, magnificence, lustre that is possible to conceive….”

King Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe’s last audience was to Major General Hay Macdowall. The events of this expedition on April 9, 1800 are given in the diary maintained by Captain William Macpherson. The throne is described as “a large chair placed on a platform three or four steps high, it seemed to be plated with gold set with precious stones, and to be like his attire very rich and magnificent …”

On February 15, 1815, the Kandyan Throne was discovered while the palace was being sacked on Governor Robert Brownrigg’s orders.

The first reference to the Throne after the British subdued the whole country in 1815 -was by John Davy (1819): “The royal throne was of plated gold, ornamented, was either dressed in the most magnificent robes, loaded with a profusion of jewelry in a complete armour of gold ornamented with rubies, emeralds and diamonds.”

It was in 1849 that Charles Pridham, the English historian and writer gave the most detailed description;

“The ancient throne of the Kandyan sovereigns or the last century and a half, resembled an old armchair, such as is not frequently in England. It was about five feet high in the back, three in breadth and two in depth, the frame was of wood, entirely covered with thin gold sheeting (studded with precious stones), the exquisite taste and workmanship of which does not constitute the least of the beauties, and vied with modern best of modern specimens of the works of the goldsmith.

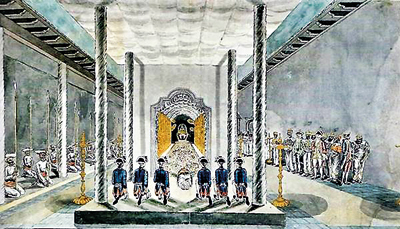

Dutch embassy to the King of Kandy in 1783 by Jan Brandes (from Illustrations and Views of Dutch Ceylon 1602-1796)

“The most prominent features in this curious relic were tooled lion sphinxes, forming the arms of the throne or chair, of very uncouth appearance, but beautifully wrought, the heads of animals being turned outwards in a peculiar graceful manner. The eyes were formed of entire amethysts, each rather bigger than a musket ball. Inside the back, near the top, was a large golden sun, from which the founder of the Kandyan monarchy was supposed to have derived his origin.

“Beneath about the centre of the chair, in the midst of some sun-flowers , was an immense amethyst, about the size of a walnut; on either side there was a figure of a female deity, supposed to be the wife of Vishnu or Buddha, in a sitting posture, of admirable design and workmanship; the whole encompassed by a moulding formed of bunches of cut crystal, set in gold; there was a space round the back (without the moulding) studded with three large amethysts on each side, and six more at the top. The seat inside the arms and half way up the back, was lined with red velvet.

“The foot stool was very handsome, being ten inches in height, a foot broad and two feet and half long; the top was crimson silk, worked with gold; a moulding of cut crystal ran about the side of it, beneath which in front were flowers studded with fine amethyst and crystals. The throne behind was covered with fine wrought silver; at the top was a large embossed half-moon of silver, surmounting the stars, and below all was a bed of silver sun flowers. The sceptre was a rod of iron, with a gold head, an extraordinary but a just emblem of his government.”

Ananda Coomaraswamy (1881-1946) when he examined the throne made the following observation in his magnum opus Medieval Sinhalese Art (1908).

“The Throne now referred to is now at Windsor Palace, where by the kindness of Mr. Fortescue, I have had the opportunity of examining it. It is a large arm chair, covered with repousse’ Gold plate set with gems, amongst which are few turquoises, the only one I have seen in Kandyan work. The other gems are mainly amethysts and crystal. The arms end in characteristic lions. The back has a sun face in the centre, flanked by divas on lotus thrones. The detail of the work is very beautifully executed. The remainder of the gold plate is chased in somewhat florid style with designs of pine apple, sun flowers and acanthus foliage type, suggestive of European influence. On the top of the back are three crystal balls”.

During the years when the throne was stored in Windsor Castle, it was lent to various members of European Royalty for their investiture ceremonies – used by Victor Emanuel of Italy in 1861, by King Haakon VII of Norway in 1906, and King Manuel of Portugal in 1908.

In 1934, with the accord of King George V, the throne and crown were returned to Ceylon during a royal tour by the Duke of Gloucester and it then figured prominently in the island’s independence ceremonies in 1948. With the throne, the crown, the sceptre, sword and other items of the last King of Kandy’s regalia were also returned to Ceylon with much ceremony.

P.S: Thieves who broke into the Colombo Museum in the 1980s, vandalized the throne and other regalia, removing several rare precious stones including a number of large amethysts.

It took Dr. Roland Silva, the then acting Archaeological Commissioner a great effort to restore the damaged parts of the throne which now remains as a symbol of the country’s royalty.