Prof with an eye for temple art that captures the essence of Vesak

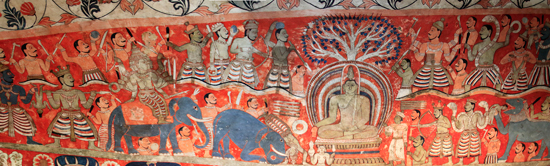

A painting at the Veheragalla Samudragiri Raja Maha Viharaya, Mirissa in the Southern Style of the Kandyan Era, circa late 19th century. Here the colonial influence is evident in baby Siddhartha’s dress, similar to a baby shirt, as he walks on the lotus flowers (to the right of the painting).

As Vesak, the birth, enlightenment and parinibbana of Buddha, the gentle philosopher who spread the message of maithriya draws close, many are the paintings down the ages which have captured this thrice-blessed day.

A medical professor, who in her free time, with camera slung on her shoulder treads the unbeaten path to remote areas to capture temple art, gives an insight into the intricacies of such paintings where Vesak has been portrayed in distinct styles in four different periods.

“Sri Lanka has a long tradition of temple paintings spanning about 2,200 years starting from the 3rd century BC. Outside India, these are the oldest Buddhist visual drawings in South Asia. These paintings are a blend of aesthetic and religious overtures and despite being influenced by Indian art, have a style unique and indigenous to Sri Lanka,” says Prof. Chandanie Wanigatunge.

Prof. Chandanie Wanigatunge

Delving deep into the less well-explored aspects of the four distinct phases of temple art, she laughingly calls it “an untutored, quasi-structured foray”.

The four phases are: the Classical Period from the 3rd century BC-13th century AD; the Period of the migration of capital cities from the 13th-17th centuries; the Kandyan Era during the 18th &19th centuries which has the two distinct schools of Kandyan and Southern; and the Modern Era from the 20th century onwards.

Before riveting her gaze on each phase, she says that temple art with the simple intention of propagating the teachings of the Buddha is found on any available surface – from the rock surfaces in cave temples to brick walls, wooden doors and pillars and even cloth. The paintings usually depict the life events of the Buddha, his previous births and other important events. They also include the lifestyles of people during those times, with occasional evidence of social commentary.

“In the Classical Period, the drawings are in the style of the Ajanta and Sigiriya paintings. It is through thin and thick lines that expressions have been brought forth,” says Prof. Wanigatunge, pointing out that drawn on large expanses of walls they exude grace and artistry and can be seen in the small cave temple in Pulligoda (close to Dimbulagala) and, of course, at the Thivanka Pilima-ge in Polonnaruwa.This style almost disappeared with the Chola invasion of Kalinga Magha.

This Modern Era (circa mid-20th century) painting of the birth of Siddhartha at Bellanwila is artistic and classical and the lines graceful. Photos by Prof. Chandanie Wanigatunge

Journeying through history, she then refers to the period of migration of capital cities, where such paintings were few and far between, most probably giving way to the ravages of time and the suppression of Buddhism by Kalinga Magha, as he moved south from his northern kingdom and the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa Kingdoms had to remove their capitals to safer locations.

This period is referred to as ‘Gampola & Kotte’ by eminent archaeologist Prof. Senaka Bandaranayake, with most temples such as the one in Hindagala seeing these paintings being damaged as they were in the occupied territories during colonial rule, she says.

Next was the Kandyan Era, once again when Ceylon was under colonial rule and Buddhism faced many vicissitudes, where it was only in the Kandyan Kingdom that there was freedom for the expression of Buddhist art but there was also the Southern School, with both styles having an overlap.

With monks unable to seek upasampada (the Buddhist rite of higher ordination) and Buddhism being relegated to the background, it had been gannin-nanses, married laymen living in temples, who would probably have engaged in temple art to draw people to these sacred places, she suggests, adding that there is no scientific basis for her beliefs.

“Most of these paintings are in the Raja Maha Viharas, the temples built by the reigning kings. Both the Kandyan and Southern Schools seem to have given simple messages through drawings on the life of the Buddha and his previous births which form the Jathaka Katha, using theeru-theeru (little strips). The story in paint going in a narrow strip or panel along the entire length of the wall, unfolded from left to right and followed through on reaching a corner from right to left. A gap between two stories would be filled with the drawing of a small tree or flower,” says Prof. Wanigatunge.

This painting at the Uda Viharaya of the Budugehinna Raja Maha Viharaya also called the ‘Punchi Dambulla Len Viharaya’ in the Kandyan School style depicts the Maara Paraajaya or ‘Vanquishing Maara the Evil’. The hand gesture of the Buddha, the Bhoomisparsha mudra asking the Mahee Kantha (Earth Mother) to bear witness to him attaining Enlightenment is depicted clearly.

These strips of art had features unique to their location and were drawn by siththara parampara (clans of painters living in particular regions), it is understood, with the Kandyan School drawings not too crowded but in comparison, the Southern School work being packed with detail.

While examples of such work under the Kandyan School can be found in Kandy, Dambulla and Yapahuwa too, the Southern School paintings are seen along the coastal belt from KandeViharaya in Aluthgama onto Hambantota, with every city having a temple with these drawings.

Looking at the drawings closely, Prof. Wanigatunge says that both the Kandyan and Southern School portrayals are child-like giving a two-dimensional view. A painting on the full story of the birth of Siddhartha is depicted in this manner at Mirissa’s Samudragiri Raja Maha Viharaya.

A group of deities, circa 7th or 8th century (late Classical Period) at Pulligoda.

Maara Paraajaya or Vanquishing of Maara who tried to dissuade Siddhartha just before he attained Enlightenment has also been a “favourite” topic of Buddhist artists and some of the best paintings on this are in the Dambulla cave temple.

A pointer that clans of painters in a region may have given of their labour of love to different temples could be the upper cave complex of the Budugehinna, a lesser known cave temple off Galewela. The walls of these tiny caves are covered with exquisite paintings of the Kandyan School, she says.

Moving to the Southern School style, Prof. Wanigatunge casts her eye on some of the best preserved murals of the Buddha Charithaya, Jathakas and hell scenes at the Kathaluwa Ranwelle PuranaViharaya where every inch of the walls and roof of the corridor around the inner sanctum are painted in amazing detail.

Meanwhile, in the Modern Period, the paintings of M. Sarlis, Somabandu Vidyapathi who drew “amazing” murals at the Bellanwila temple, Solias Mendis (Kelaniya) and George Keyt (Gothami temple at Borella) were more advanced than the earlier 2D portrayals in the Kandyan and Southern School style, she says.

These were more life-like with a Renaissance influence being evident, with the drawings full of colour and vivacity covering big panels.