Triple win with double misery

View(s):

The families, which lost the care and protection of the mother, are left with the father and the children. The researchers found that not only the children, but also many fathers appear to have crossed the boundaries of their behaviour patterns.

Although the focus of the research was not on this particular issue, the information they heard aroused their curiosity to find more details, which I quote below. It is understandable that we must avoid any reference to actual names of persons and places.

Daughters in mother’s clothing

It was tragic to find out that many children grow on their own as they wish, without corrections and directions from the mother. They have become not only the easy targets for abuse by others, but also the victims of being exposed to the X-rated social media and Internet sites. Children’s tragedy is particularly the case of many families in which there were drunkard fathers.

Fathers addicted to alcohol were found to be having a gala time. As they now receive good money from their wives working abroad, they seem to have raised their consumption patterns. Those who used to smoke local “beedi”, now shift into cigarettes. Cheaper illicit alcohol has been replaced by costly licit liquor. Simple “bite” packets to go along with drinks have been replaced with home-made hot meat dishes.

Elder female children have become the most vulnerable in the “motherless” family transformation process. Some of them had ended up in tragic affairs with boys and men. If not, they have filled the vacated role of the mother at home, by undertaking cooking, washing, caring the younger siblings and all sort of house-keeping. It is an open secret that the elder daughters in some families have also become the “new wives” of their own fathers! In one such incident, which has also been brought to the law enforcement authorities, the father said: “She looks like mother and, she also wears mother’s clothes that are left at home. When I come home in the evening (after getting drunk), I see her as none other than my wife”.

After all, it is also difficult to say that the mothers who left for work under unknown conditions with unknown employers and in unknown lands are doing well. Many of them have longer working hours, harder working environments, lower payments and, fewer work rights. In fact, I believe that they would not decide undertaking such work abroad, if they had a choice in the home country.

Sri Lankan “remittance economy”

East Asia Forum – an online journal of the Australian National University (ANU)-, recently published an article about Sri Lanka, introducing the country as a “remittance economy”. There is nothing surprising about this title – the remittance economy, because the amount of money remitted by the country’s migrant workers occupies such an important place in our economy.

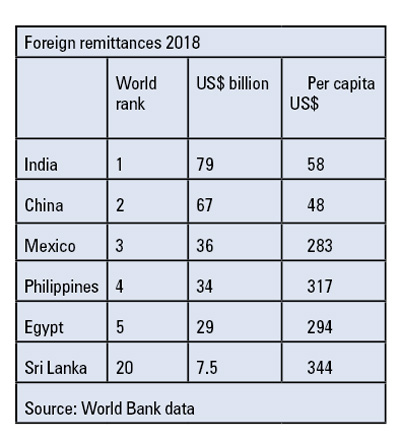

According to World Bank estimates, reported remittance flows to low-income and middle-income countries in the world amounted to US$529 billion in 2018. The top five remittance-recipient countries in the world are India with $79 billion, followed by China ($67 billion), Mexico ($36 billion), the Philippines ($34 billion), and Egypt ($29 billion).

Sri Lanka has $7.5 billion remittance receipts in 2018. Occupying the 20th rank position, Sri Lanka is not too far from the top remittance-recipient countries in the world. If we calculate in “per capita” terms, with $344 remittance per person, Sri Lanka is on the top of even the top-five remittance-recipient countries. Thus, it makes sense to call it a “remittance economy”. This is, however, not the whole story.

File picture of migrant workers at the airport.

It is the worker remittance that has been the fastest-growing foreign exchange receipt in Sri Lanka for decades, and not our “export income”. Sri Lanka’s remittance earnings are higher than the earnings from the country’s largest export item – textiles and garments ($5.3 billion), and only a little less than the earnings of the country’s total industrial exports ($9.3 billion).

Worker remittances are such an important source of foreign exchange for cushioning the country’s external trade deficit which is nearly as big as our total export earnings. Therefore, we love to have our remittance income increased, because we can cushion our trade deficit, meet our import expenditure, and defend the exchange rate at least to some extent.

Case for a “triple win”

There has been a surge in “worker remittance” to developing countries which coincide with a parallel increase in research and publication on “migration and development”. Most of these analyses have come to describe labour migration as a “triple win” case.

The first “win” is for the families of the migrant workers, because worker remittances provide an avenue to escape from poverty and, a financial asset for investment. The second “win” is for the country which receives worker remittances, which would ease the foreign exchange shortage as well as the unemployment problem. The third “win” is for the countries which accept the migrant workers, because they can solve the problem of their labour shortages.

It looks as if it is a beautiful “win-win-win” case for all three parties. I believe that, however, remittance money cannot compensate for the social cost of the families of migrant workers that we have elaborated in our opening story. Money is important, but if that money is that much costly, what do these families have achieved in net terms?

And the evidence suggests that remittances are rarely spent by poverty-stricken families on investment and businesses. Instead, they are mostly used for repaying debt, building a house, financing consumption, and purchasing household appliances and jewellery.

The second “win” is for the home country of the migrant workers, and this is where the national problem is. It is true that remittance money would temporarily cushion the foreign exchange shortages, finance the necessary imports, and defend the exchange rate. On the contrary, however, the continuous dependence on remittance shows nothing but the “inability” of that country. It is the nation’s inability to accommodate its labour for productive work and to reward that labour adequately. After all, countries prosper by raising their exports of goods and services, and not by exporting their men and women.

Double misery

If a country’s foreign exchange earnings come from exporting its labour, it shows the misery of the families trapped in poverty on the one hand, and the misery of the country which is not capable of providing productive jobs for its own people on the other hand.

Having recognised the problems of migrant workers with high “women’s share” and high “unskilled share”, Sri Lanka has been promoting male-worker migration as well as skilled-worker migration. In fact, the share of male-worker migration and skilled-worker migration has increased over the years. Nevertheless, it is exactly these two categories that are critically important for raising and sustaining our economic growth.

The increased share of male-worker and skilled-labour migration, therefore, confirms the “inability” of our economy. Perhaps, Sri Lanka might be the only country in the world, which invests in developing its human resources with “free education” financed by public money for the use of other countries in the world. And people too, who don’t have a choice, may take up the only choice available for them to work for another country.

(The writer is a Professor of Economics at the University of Colombo and can be reached at sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk).