Sunday Times 2

Global and national diplomacy: Making connections

There was a time when Sri Lanka actively engaged in UN affairs and UN issues, although they did not affect Sri Lanka directly. They were concerned with issues such as non-alignment, North-South economic negotiations, the Arab-Israeli dispute in the context of the UN, and other regional issues.

When the United Nations initially developed its policies on issues such as poverty in developing countries, and the priority to be given to basic needs in these countries, Sri Lanka’s experience in advancing human development (education, health) offered guidelines to the development of UN policies in these areas.

Jayantha Dhanapala: One of the last diplomats from Sri Lanka to be engaged on broader issues of international relations

Sri Lanka’s engagement in these larger issues facing the international community, gave it an important place and standing in global affairs. Many Sri Lankan diplomats and other officials were actively engaged in New York and Geneva on these issues. This was prior to 1977. Since that time, Sri Lanka has lost its stature as a consequence of internal upheavals and the withdrawal from wider engagement on international issues. Jayantha Dhanapala was one of the last diplomats from Sri Lanka to be engaged on these broader issues of international relations.

Jayantha Dhanapala had a distinguished career in Sri Lanka’s Foreign Service and the United Nations. He was Ambassador in Washington and the Permanent Representative to the UN in Geneva.

Later, he headed the UN Disarmament Institute in Geneva. As a representative of Sri Lanka, he was elected as the Chairman of the Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which successfully extended this crucial international treaty. Then he was Under Secretary General at the United Nations in New York, with responsibility for world disarmament. Subsequently, he was appointed President of the Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs, which is a prestigious non-governmental body, whose founding fathers were Bertrand Russel and Albert Einstein. As a national and global diplomat, Dhanapala has impressive credentials. He was one of the outstanding personalities of his generation in Sri Lanka.

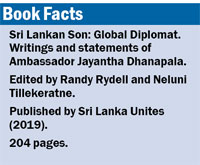

The volume under review is a wide-ranging selection of his speeches and statements to various, largely non-governmental organisations. He had been invited to address some of the most prestigious bodies the world over in the fields he was concerned with. The volume covers issues such as world disarmament, nuclear non-proliferation, international terrorism, international law, international civil society, and peace education. Then there are speeches and statements he has made which have a greater resonance in Sri Lanka – on peace building in the country. The role of the diplomat, and the University of Peradeniya of which he is a distinguished alumnus. Let me select a few of these subjects for more extensive comment.

World disarmament has been a theme since the end of the First World War and the establishment of the League of Nations, the predecessor organisation to the United Nations. One of the primary responsibilities of the League of Nations was disarmament. The UN took over the League’s work. Dhanapala refers in his speeches and statements to the contribution made by the UN in this field, and there are many notable achievements on a limited scale, like the Small Arms Treaty, and the control of chemical weapons.

But during the whole period of the UN, instead of disarmament the world has experienced a massive building up of arms by most countries. Dhanapala refers to the role of the arms trade and to the effects armaments spending has on the development of poor countries. Although he does not refer to it, one can observe this phenomenon in Sri Lanka, where large expenditure commitments are now being made annually on national defence, and obviously, at the expense of expenditures on development.

Apart from discussing arms control on a global scale, should not the UN be engaged actively promoting discussions at the national level on these issues, especially in relation to its Millennium Development Goals and other human development indicators. Of course, there is a reason for arms expenditures, as each country looks at its own security situation. The idea is that if you want peace, prepare for war.

Apart from discussing arms control on a global scale, should not the UN be engaged actively promoting discussions at the national level on these issues, especially in relation to its Millennium Development Goals and other human development indicators. Of course, there is a reason for arms expenditures, as each country looks at its own security situation. The idea is that if you want peace, prepare for war.

Coming to nuclear arms and non-proliferation, Dhanapala discusses these issues in many of his speeches and statements. There was a time when the nuclear question was uppermost in people’s minds and there were huge campaigns for nuclear disarmament. These campaigns were somewhat similar to the current ones on Climate Change. Is it that the perception of the threat from nuclear weapons has receded to the sidelines of global affairs? In an instructive speech made by Dhanapala in Uppsala, Sweden in 2000, he has discussed the prospects for Nuclear Free Zones which is yet relevant. In this speech, he referred to the proposal made by Sri Lanka for an Indian Ocean Nuclear Free Zone in 1971.

International non-state terrorism is now a major problem for most countries. This volume has many references to this phenomenon, especially subsequent to the events in New York in the year 2001. The suggestions are mainly for cooperation among states to control weapons of mass destruction.

Regrettably, there are no extensive references to the urgent need for improved intelligence cooperation systems which are vital to the control of international terrorism. Governments at times take the easy way out of building up arms to counter terrorism. Intelligence is as or more important to control terrorism effectively, and it is far cheaper. Even in Sri Lanka, the recent Easter Sunday incident can largely be attributed to a failure in intelligence analysis. More resources, both financial and brainpower, have to be invested to build up appropriate intelligence capacities.

Dhanapala attaches much significance to peace education, in one form or another to overcome these massive global problems. Undoubtedly, this is a laudable approach.

However, we have to realise that thousands of years of religious education, have not been successful in the elimination of war or terrorism, and religious education is about peace. We certainly must proceed with educating the young and old on these issues, but it can be done by a greater engagement in the teaching of the humanities and subjects such as civics.

There is no real need to invent a new subject, although no harm is done by such an approach.

In Sri Lanka today, there has been a significant decline in the quantity and quality of teaching of humanities. Technological education is now the craze, and in university institutions, students who pursue courses in technology have absolutely no access to learning the humanities. This is an issue which civil society in Sri Lanka should reflect on.

Since returning to Sri Lanka, Dhanapala has made several speeches on issues which include the rise of China, on Pablo Neruda, on the University of Peradeniya, and others.

For reasons of space, I can comment on them only briefly. With regard to the rise of China, there is more rethinking required to what Dhanapala has said. China’s economic achievements are impressive, unique in the history of mankind. But in terms of political development, human rights and democratic governance, there are major concerns. One of the greatest deterrents to war and the assurance of peace is democratic governance.

Dhanapala’s comments on Pablo Neruda, the Chilean Nobel Prize winner for literature, are most interesting and highly relevant to the diplomats of the current generation. Our generation knew of Pablo Neruda, who lived in Ceylon in the late 1920s and who was a diplomat for his country. Although not all diplomats can be scholars, there is a great opportunity for diplomats to be more scholarly in their assessments and analyses. Neruda established extensive contacts with intellectuals of his time in Colombo, and similarly, most of our diplomats can do the same in the countries they are accredited to.

Finally, let me go back to our beginnings. I first knew Jayantha Dhanapala at Peradeniya University in the 1950s, 60 years ago. His brief speech on the role of Peradeniya University made a few years back is included in this volume. He is too much of a diplomat to analyse in any depth the ills and the ailments that have affected our old University.

In the 1950s, we had an elite education at Peradeniya, with English as the medium of instruction. Although the education was elitist (English offered access to wider reading), the undergraduates did not come from any social elite. By the 1950s, the early products of the central schools and other schools in smaller towns, were sending students to Peradeniya. Probably, the majority of undergraduates in our time came from Sinhala and Tamil speaking or bilingual homes.

Dhanapala identifies E.R. Sarathchandra (the producer of Maname and Professor of Sinhalese) as the emblematic academic of his time. Although the medium of instruction was English in our time, that was no obstacle to a thriving Sinhalese culture at Peradeniya. One of the big mistakes in my view was that English was not kept as the medium of instruction in universities. They did keep English for medical education.