The bridge her grandfather built

Retracing her grandfather’s footsteps: Sue Talbot at the viaduct Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Framed within the tunnel, its appearance is first heralded by two long and loud toots, while in reply there are two whistles from the ground.

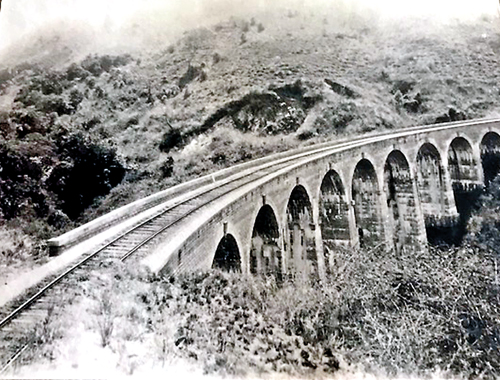

As the blue train from Colombo to Badulla rumbles along at 3.20 in the afternoon, navigating Demodara’s curvy nine-arch bridge, many on the train and the ground gaze in wonder at an engineering marvel.

It is the viaduct at Gotuwela, between the Ella and Demodara stations, which consists of nine arches and is part of the up-country (Uva) railway. From this unique bridge, Sri Lanka’s splendour spreads before the beholder.

Clicking loads of photographs including selfies of the passing train and the picturesque setting that day, many were unaware of a momentous moment – the granddaughter of the creator of this engineering marvel being right there, emotional and in awe of what Harold Cuthbert Marwood and his team had created.

Five-year-old Elizabeth with Marwood’s wife Margaret in Ceylon

Later seated close to the viaduct, sipping thambili through a straw, Susan Talbot can only imagine the trying conditions her innovative grandfather, a colonial railway engineer and his team would have overcome in the mist-laden distant past more than 100 years ago.

The wilderness would have daunted anyone as also the arduous and hilly terrain, as Marwood and his team pored over drawings, checked out the quantities of materials needed and how they would lug them there.

On her first visit to Sri Lanka recently, we meet Sue, her husband Richard and friends Andrew Holder, Hazel Ward and V. Kuhanendran by the railtrack on the nine-arch bridge, quite breathless, having in their naivety, clambered and slithered down the perilous mountainside, on the advice of sure-footed locals.

They had taken lodgings at a guesthouse atop a hill overlooking the Demodara Pass and Sue had watched the trains pass-by from this vantage point. Early that morn she and her party had also taken the short rail-ride from Badulla to Ella having driven up to Badulla. While the others had woken up bleary-eyed to the alarm at 20 past 5, Sue had been “so excited” that sleep had eluded her from 3 O’clock.

“It was magnificent, really magnificent,” exclaims Sue whose visit here was in fulfilment of a personal yearning as well as the urging of her 92-year-old mother Elizabeth Mary, Marwood’s younger daughter, who had been born in Ceylon.

As Sue stood with her hands on the vertical rails (handrails) of the train, the wind in her hair it was “a really happy moment”……….all the sepia-tone photographs back home in Buckinghamshire finally making sense.

Who was Harold Cuthbert Marwood, the railwayman impeccably dressed in full suit including puttees (leg-wraps from ankles to knees) even in the sweltering tropical heat and wielding a cane and carrying a white safety helmet?

Harold Marwood

For Elizabeth, the adored daughter whom Marwood had been blessed with at 50, he was kind and fun-loving, with a great sense of humour. Unassuming and quiet he was, but efficient and hard-working. If assigned a task, there was a 100% guarantee that he would do it to the best of his ability. He underplayed his achievements because he thought “this is my job”.

While Elizabeth was sent back to England and boarding school when she was six years, Marwood, after his stint at the Ceylon Government Railway (CGR), had been requisitioned much later to return home and work in Cardiff. But, says Sue quoting her mother, he had been unsettled because he missed Ceylon, his one-and-only overseas posting.

Living in retirement at Folkestone, Marwood had been 72 when he died of stomach cancer in 1948.

In Colombo, Sue had visited the Galle Face Hotel, a must-see in a trail that she wanted to re-trace, her Mum having told her many a tale of her time here.

“My mother is full of stories from her childhood. She told us how her father took her to the Galle Face Hotel and they were moving house at the time and she thought the Galle Face Hotel was her new home,” says Sue, adding that her Mum and her parents lived in Colombo for a bit of time.

They had three homes in Colombo, Kandy and Nuwara Eliya and it was in Nuwara Eliya that they were based most of the time. Her mother has a story that she remembers vividly, of being driven by her father in his Morris Minor into jungle areas, whereupon she and her mother remained in the car tucking into some sweets while Marwood went about his work planning the design of the railtrack.

For his descendants, these are exotic tales from a different time and a land faraway, but for Sri Lankans Marwood has left behind a beautiful and enduring legacy – the ‘Arukku Namaye Palama’ also called the ‘Bridge in the Sky’ that they hold close to their hearts.

| ‘Declare it a protected monument’ | |

Why is Demodara’s nine-arch bridge so special?“It is an extraordinary bridge,” says railway veteran K.A.D. Nandasena, while train aficionado Vinodh Wickremeratne nods vigorously. Why is Demodara’s nine-arch bridge so special?“It is an extraordinary bridge,” says railway veteran K.A.D. Nandasena, while train aficionado Vinodh Wickremeratne nods vigorously. A strong plea from both is that the nine-arch bridge should be declared a protected monument. Getting down to technicalities, they say that the bridge has stood the test of time, for over a century, without any signs of weakness. “A concrete mixer, a crane and two derricks were the only machinery used in this construction. Marwood had got scaffolding erected and built-up with piers forming platforms between them. The platforms consisted of rails bolted and braced together,” they point out, adding that transport was by pack-bulls. “Even today, the access road to this point is limited to small vehicles but Marwood designed and built the bridge in two years.” Here are highlights from a report submitted by Marwood on the ‘Construction of a concrete railway viaduct in Ceylon’:

The work was completed in January 1919 by the Railway Construction Department, a temporary branch of the Public Service, with the assistance of local petty contractors who supply the labour. The rates for the work are fixed by the department which also provides accommodation and rice. The work had been “put in hand” by Marwood as Engineer in charge of that section of the railway, under the approval of the Chief Construction Engineer, Railway Extensions, M. Cole Bowen. Marwood’s report had been submitted to the Institution of Engineers, Ceylon in 1922.

|