Columns

Reflections on the economy’s long term growth and development

View(s): Reflecting on the long-run economic development of the country is hardly appropriate in the current state of the economy when a recovery or a moderate growth is all that can be expected. Nevertheless, achieving a higher sustained economic growth is what the nation has failed to achieve but must aspire to attain.

Reflecting on the long-run economic development of the country is hardly appropriate in the current state of the economy when a recovery or a moderate growth is all that can be expected. Nevertheless, achieving a higher sustained economic growth is what the nation has failed to achieve but must aspire to attain.

The preconditions required for an economic take-off are the same as for the immediate economic recovery. These are peace, security, political stability, social harmony, law and order, the rule of law, certainty in economic policies and their effective implementation.

In as much as these are preconditions for long-run economic growth and development, these are the very conditions that the country is unable to achieve at present for an economic recovery. These preconditions are necessary but not sufficient.

Economic policies

Appropriate and pragmatic economic policies have to be adopted to propel the economy to a higher level of sustained economic growth. The country’s political culture and milieu have been inimical to adopting such policies in most periods of the country’s economic history. South East Asian countries that are known as the Newly Industrialised Countries (NICs) and China and Vietnam later developed owing to their adopting pragmatic economic policies.

Changing political regimes, reversals in fundamental economic policies and ideological commitments that prevent the adoption of pragmatic policies have been among the reasons for the economy performing at lower than potential. The 3.5 percent annual average growth in the seven decades after independence is woefully inadequate and much below the country’s potential.

Obstructionist opposition

Obstructionist opposition

Furthermore, Sri Lanka’s opposition parties are largely known for their obstructionist policies that thwart the implementation of development projects. Recent economic development projects have faced severe organised opposition. The latest illustration of this being the opposition to the development of the Colombo Port’s East Container Terminal (ECT) discussed in a recent column.

Economic take-off

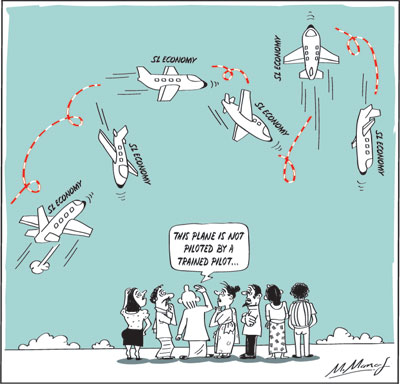

In 1960, W.W. Rostow’s celebrated book ‘Stages of Economic Growth’ postulated that once the preconditions for development were achieved in a country, the economy would take off like an aircraft and achieve sustained economic growth and development.

Fluctuating growth

Regrettably these features of aerodynamics have not been the feature of Sri Lanka’s economic story. It is more like a take-off followed by several nose dives and then in flight before another dip in altitude. In fact, the country did not have stable and continued preconditions for development.

Post-independent growth

Post-independent economic growth has hovered around a mere 3.5 percent — with a few years recording a growth of about 8 percent. It was negative in a few troubled years, around 5 percent in some and dropping to an annual average of only 3 percent during the current regime. So much for Vision 2020, when we were to become a rich country with a high per capita income!

Progress

It would be inaccurate to interpret this story as one of economic stagnation. The country is much more developed than at independence. This is borne out by the fact the country has moved into a middle income country with a much higher real per capita income than in the 1950s. Poverty has been reduced; housing and other amenities like potable water and electricity are accessible to a large proportion of the population; cars motor cycles, trishaws and phones are owned by a large number. The road network is much improved, though public transport is not developed adequately. Large towns have emerged in what were small underdeveloped villages.

Social development

The country’s proudest achievement is its human development indicators: high life expectancy, adult literacy, high school enrollment and low mortality rates. Sri Lanka ranks high in the UN Human Development Index (HDI). Abject poverty and unemployment have fallen to below 5 percent.

Below potential

Notwithstanding these improvements, the lament is that the country with its resources and capacities could have achieved much more. The economy is growing at less than half the economic growth of South Asia of 7 percent.

According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), this year’s expected growth of Bangladesh is 8 percent, India 7.2 percent, Maldives 6.5 percent, Nepal 6.2 percent and Bhutan 5.7 percent. The two slow growing South Asian countries are Pakistan at 3.6 percent and Sri Lanka at 3 percent.

Sri Lanka has failed to establish a united society without social tensions, security and law and order. Sri Lanka’s unworkable political hierarchy has compounded the difficulties of adopting and implementing economic policies. Until these issues are resolved and a strong and stable government is established, the economy will continue to grow at a slow pace.

Political culture

Much of this under-achievement can be attributed to the politics of the country. At present, we have reached a state of ungovernability. People are more or less resigned to waiting for a new regime that is politically stable and capable of implementing the correct economic policies.

The disillusionment with the political leadership is so widespread that there is a swell of opinion that the country must be ruled by a younger generation of educated persons. There is much sense in this stance for the country’s long-run economic development that requires such a leadership to establish the preconditions for economic development.

The communal politics, social tensions and communal disharmony could hamper economic growth for many years to come. The sober and concerned citizens of the country would have to wait in expectation of communal and social harmony and lesser social tensions that would bring about a normalisation of economic activities and enable economic development.

In conclusion

The story of Sri Lanka’s economic development has been a series of missed opportunities. It is a story of communal politics disrupting an economic take-off; it is a story of ideology impeding the adoption of pragmatic economic policies and a tale of increasing corruption and lack of financial and political accountability. When will all this change?

Leave a Reply

Post Comment