Post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth – two sides of the same coin

What doesn’t kill me makes me stronger – Nietzsche

On April 21, the series of bombs that exploded killing 253 persons and injuring over 500 left the nation in a state of shock. Less than a month later the sense of unreality and numbness still continues. More so because we have enjoyed a state of peace for nearly a decade. I thought it would be timely to discuss the effect of such a trauma on us humans; post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and the lesser known more positive aspect of the impact of trauma; post-traumatic growth (PTG).

PTSD first came to public and scientific attention following the Vietnam War. Pic courtesy AFP

The impact of a disaster or trauma on the human psyche has been documented since ancient times. Historians often cite the description by Heradotus of an Athenian spearman Epizelus who at the Battle of Marathon against the Persians in 49O BC, lost his sight though he was not physically injured.

PTSD first came to public and scientific attention following the Vietnam War when the American Psychiatric Association in 1980 added it as a diagnostic category to its manual of mental health disorders. Previously it has been known by various names such as soldiers’ heart, shell shock, combat fatigue or war neurosis.

The term trauma, derived from the Greek for wound, is not limited to war and is defined as a stress outside normal human experience where persons are exposed to death and serious injury or even to the risk of such an eventuality. Trauma could be natural disasters such as earthquakes, floods, landslides, or man-made such as bomb blasts, firearm injuries, industrial accidents or serious traffic accidents. In the past, day-to-day troubles such divorce, losing jobs or child birth were not considered traumas. But it is now recognised that even these could lead to symptoms of PTSD and whether or not PTSD develops is also dependent on the affected person’s personality and social circumstances.

There are four main categories of symptoms. First, the person has intrusive recollection of the event as memories, dreams or flashbacks (total recall including sensory experience of the event). Second, the persons will actively avoid situations or objects that remind them of the event. Third, the persons are highly aroused and likely to be startled or frightened by sounds or pictures similar to the trauma. Fourth, there is a change of mood or effect. A classic response is emotional numbness where the person is seemingly indifferent to normal human emotions such joy, happiness or sorrow.

Though most people will suffer varying degrees of these symptoms, after a trauma it is important to know that only when the symptoms are intense and persistent that a diagnosis of PTSD would be appropriate. By definition PTSD can only be diagnosed if symptoms persist beyond one month. This time period is based on the observation that most people will have a significant reduction of their symptoms in a month.

On March 6, 1987 a large ferry boat carrying nearly 500 passengers and their vehicles left the port of Zeebrugge in Belgium for Dover, England. The captain was unaware that the bow doors had not been closed. Within minutes of leaving the harbour, water flooded in through the open bow doors and the boat capsized. One hundred and ninety-three people died in one of most horrific maritime accidents of peacetime.

On March 6, 1987 a large ferry boat carrying nearly 500 passengers and their vehicles left the port of Zeebrugge in Belgium for Dover, England. The captain was unaware that the bow doors had not been closed. Within minutes of leaving the harbour, water flooded in through the open bow doors and the boat capsized. One hundred and ninety-three people died in one of most horrific maritime accidents of peacetime.

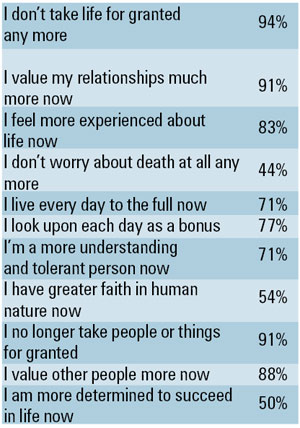

A young psychologist Stephen Joseph of the Institute of Psychiatry in London was asked to assist the survivors with psychological help. As expected, he found that most of them met the criteria for PTSD in the first months following the disaster. Many of them had difficulties at home and work. During his interviews Stephen Joseph noticed something strange. He found that the trauma had left the survivors with a new outlook on life, a mix of negative and positive. Here is the list of positive changes in outlook with the percentages of people agreeing as reported by him.

Further research has confirmed these findings and we now know that, counterintuitively, trauma can change life positively. But why is it that some survivors report positive changes but others do not? Can these others be helped to change their life for the better?

People respond to trauma differently. These coping types could be compared to trees on a hill during a storm. One tree is buffeted by the wind but is unbending and remains unaffected after the storm has passed. Some people are like that, they stand unbending and emerge unscathed. Such persons are said to be resistant. A second tree bends, does not break and returns to its original shape. Likewise, there are people who bend under stress but bounce back afterwards. These persons have recovered to their original state. But it is not these two categories of persons who experience posttraumatic growth. A third tree bends in the storm but does not return to its original shape. With time it grows new branches and roots but it is changed forever. It is the same tree but different. Similarly, some people grow following a trauma. They are emotionally scarred but their view of themselves, the world, their future goals have changed positively. They have undergone post-traumatic growth.

People respond to trauma differently. These coping types could be compared to trees on a hill during a storm. One tree is buffeted by the wind but is unbending and remains unaffected after the storm has passed. Some people are like that, they stand unbending and emerge unscathed. Such persons are said to be resistant. A second tree bends, does not break and returns to its original shape. Likewise, there are people who bend under stress but bounce back afterwards. These persons have recovered to their original state. But it is not these two categories of persons who experience posttraumatic growth. A third tree bends in the storm but does not return to its original shape. With time it grows new branches and roots but it is changed forever. It is the same tree but different. Similarly, some people grow following a trauma. They are emotionally scarred but their view of themselves, the world, their future goals have changed positively. They have undergone post-traumatic growth.

There are many aspects to post-traumatic growth but three in particular are common. They are: personal changes, philosophical changes and relationship changes. Personal changes include new inner strengths, greater wisdom and compassion for others. Philosophical changes are common too. There is a newfound sense of the gift of life, a greater awareness of the here and now with appreciation of the small daily pleasures rather than expensive possessions and worldly successes. Relationship changes are also characteristic. There is an appreciation of human connection and family and friends more than before the trauma.

Next month I will discuss post-traumatic growth in more detail and also ways of fostering such growth in ourselves as well as in others affected by trauma. I will leave you with these lines from Alfred Tennyson’s Ulysses written in another context but appropriate:

“Though much is taken, much abides; and though

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are”