Laki’s green green ‘jungle’ of home

Laki Senanayake In his favourite spot overlooking the lake and jungle at Diyabubula. Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

The forest envelops Diyabubula in a close embrace and Laki Senanayake is content- it is as he envisioned it.

“Thirty or 40 years ago when I planted these trees I thought, will I live long enough to see all these branches meeting,” he says. The branches have now formed a canopy so thick that only patches of sky can be seen and Laki is only mildly regretful that he can’t see the stars in the night sky as well.

Diyabubula, Laki’s home in Dambulla, a quite unique eco-retreat is a work in progress and Laki, its architect presides benignly over this forest kingdom he has wrought from an arid Dry Zone landscape where once there was only bare land and coconut trees. He removed some 45 trees in his quest to make the property a viable agricultural venture growing chillies and soybean back in 1972. The crops thrived but markets were dismal and so after two years he and his brother who had financed it, called it off. Laki bought the land and then began growing trees, the Dry Zone varieties that flourished naturally in the area.

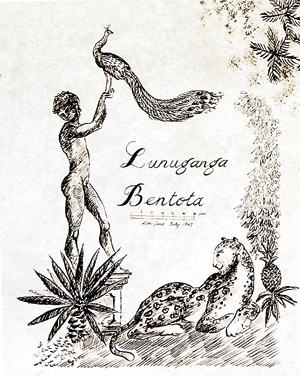

The Disobedient Peacock, a detail of the Lunuganga site plan 1962: From the Lunuganga Trust collection

This week, this artist, sculptor and man of many skills will reluctantly come to Colombo- for the opening of his latest exhibition ‘The Greedy Forest’ – the Gardens of Laki Senanayake – at the Barefoot Gallery on August 30. The exhibition will present a side of Laki that few have given credence to – Laki the landscape designer.

It was when the agriculture failed that Laki returned to architecture and painting, working with Nihal Amarasinghe and other leading architects. He remembers the first big garden he did for the Jinasena building he had designed and another for a Mrs Weerasuriya, an old rubber estate where Nihal had ‘done a very nice house’. Little by little the commissions grew- “in the last 40 years I must have done 200 gardens all over the place.” Gardens, some in the capital, others in the hill country, by the beach, even in the East and North that he created mostly with plants and trees grown from Diyabubula, from a landscaping company ‘Botanica’ that he started with his friend Noel Dias.

In those days, if he was asked to do a garden, he would produce a hand-drawn sketch first, right until the time computers no longer required that particular skill. Many of these sketches, done on tracing paper, some not even dated, he came upon rolled up in a cupboard and thus came the idea for this exhibition.

Now carefully curated, the exhibition presents his ideas, vision for the gardens, coupled with photographs taken by young photographer Luka Alagiyawanna to illustrate how they turned out in reality. Five projects are highlighted; Diyabubula, of course and the Art and Jungle Lodge (which now adjoins it), Barberyn Beach Ayurveda Resort in Weligama, Siesta Sculpture Park in Trincomalee, a Tree House in Ritigala and the Ruin Garden of the Sigiriya Village Hotel. Some of Laki’s early drawings loaned for the exhibition by the Lunuganga Trust, will also be on display.

The exhibition catalogue, compiled with equal care has contributions by architects who enjoy a close association with Laki –

The sound of water: Laki’s fountain sculpture

C.Anjalendran, Channa Daswatte, Shayari De Silva, Curator of Collections of the Lunuganga Trust and Max Moya. Their personal and critical essays present new insights into aspects of Laki’s work. “Not only has he created so many ( gardens) that deserve to be shown as the art form they are, but also by interrogating his relationship with the natural world, we just may come to understand this singular man’s transformative powers,” the catalogue’s introduction reads.

For those expecting to see gardens akin to Lunuganga and Brief, the landmark creations of Geoffrey Bawa and his brother Bevis, Laki’s wild offerings may hold less appeal. The exhibition’s title reflects Laki’s pursuit of the jungle, indeed he makes no excuses- “I do things to suit myself,” he smiles. “All my gardens are small forests,” he says, “my way is making it comfortable and cooler for the house.” Most people don’t like trees too close in case they fall on the house and his answer is to insure the house. Plant smaller trees to give shade and keep the ground around cool, he advises. At the Barberyn Resort, Weligama, confronted with scorching sunlight when walking to the rooms from the reception, he planted 20 Mahogany trees to provide deep shade. Lawns too, a favourite with most of his clients -most want it for their cocktail parties –are not his thing. He asks if the clients would actually walk around in the garden or be sitting in the house, looking at the garden- two very different things in his book.

He didn’t do gardens for Bawa though creating many sculptures for the great man. But his curator believes that Diyabubula is as worthy of attention as Bawa’s masterpiece, describing it as the finest garden in Sri Lanka since Lunuganga.

Diyabubula was a different site when Laki first descended on it. He delights in relating how the huge rock that now overlooks the pool was entirely covered in earth with only the eroded top visible and how he had the reluctant workers dig it out. It now looms over the artificial pool that dominates the landscape. The house too which was down below close to the only patch of water that existed then, moved as did the pool. “After about two years the rock had come out and so I uprooted the whole house from there and planted it here,” Laki says gesturing to its now high ground location. “It’s a better place.”

A secondary pool in Diyabubula. Pic by Luka Alagiyawanna

Writing in the catalogue, Max Moya explores Laki’s use of water in his projects which he sees as ‘decidedly pathological’. “Water preserves the integrity of his subject. Firstly there is Laki’s architecture which tends to be supported on stilts emerging from pools, of which perhaps the best examples are the water villas of the Diyabubula Art and Jungle Lodge. Functionally these also prevent termites from rotting the structure and undesired animals from entering the space of the subject, or elephants from knocking down the structure of the Tree House in Ritigala….In Diyabubula and the Tree House project, pools around the property serve to protect the very soul of his subject. On occasions where trees of significant beauty were already planted as in Siesta Park Sculpture Garden, Laki has constructed pools around them as if everything worthy must rise up from water…” Moya notes, seeing here a connection with Laki’s first ever project which was also linked to water – a design for a diving board in 1955 for the Otters Swimming Club in Colombo. Laki himself says he loves the sound of water and so fittingly, at the exhibition will be one of his water sculptures from Diyabubula.

The links are all there for Laki- his love of nature, for birds, trees, waterfalls, stemming from his early childhood, “the best time of my life” to which all his adventures later don’t quite compare, when he and his younger brother would roam the estate at Madampe, Chilaw where his mother was superintendent – “we would vanish after breakfast at 7, coming back only when hunger struck”. I was always greedy for the forest- at one time I wanted to be a tracker in Wilpattu so I could be in the forest, he recollects. The boy Laki explored, rowed, swam, hunted, drew and sketched to his heart’s content and when sent off late to Royal College hardly paid attention to his lessons. After school when his mother asked how he planned to earn his living, he told her he was an artist. That being not an option in those days, he was channelled into a job as an apprentice draughtsman in an architectural firm ‘Bilimoria, De Silva, Peiris and Panditharatne’ and thus began a colourful career on a path less trodden.

He recalls how his Trotskyite planter father would tell his mother not to worry about their children’s future but to look after the children around them whose parents didn’t have any means. His mother, the country’s first woman MP too always had others’ welfare uppermost, she would sew clothes for all the children at St. Michael’s Polwatte where she was a longstanding member of the Mothers’ Union, he remembers. In many ways, with his agricultural commune and the responsibility he still feels for the welfare of those at Diyabubula, that commitment is still continued.

The Siesta Park Sculpture Garden in Nilaweli. Pic by Luka Alagiyawanna

At 80, spondylosis has constrained mobility somewhat; yet his day begins at 4 a.m. By the time his workers arrive at 8, he has done 4 hours work, ready for a quick mid-morning nap. Back to work till evening, and when the workers leave, he switches on the 11 speakers strategically placed around the pool, modern technology employed to best effect, to listen to music, soaring through the branches.

Calls keep coming in for there’s a garden he’s making for the Sunrise hotel in Passekudah, work in the sculpture garden at Nilaweli still to do and new ideas to pursue. Those passing Kirimandala Mawatha in Colombo may have seen the huge billboard alternately promoting this exhibition and offering inexpensive digital prints of his works. “I think we should sell art cheap so that more people can have it,” he declares. The billboard he also used recently to show how one could construct a low cost house, how to rear fish very cheap and how to water a garden using a subsoil drip feed system.

He’s going to try out three dimensional sculptures with epoxy-resin though there’s hardly any more room to put the sculptures, he laughs. It’s true, they are everywhere -even high up, a tiger’s face with the sun’s rays hangs suspended and the big owl on the Mara tree, in addition to the ones on the ground. Nature never ceases to fascinate. This morning he has seen a Fish Owl perched on the horse sculpture and there’s an Ulama also around. Wonderful, he says, describing its cry, ‘like a woman being strangled.’ We leave him in the wilderness he loves best – with his sculptures and birds.

‘The Greedy Forest’ will be on at the Barefoot Gallery, from August 31 to September 16 from 10 a.m. – 7 p.m. on weekdays and from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Sundays.