Plight of SL’s public sector engineers

In 1971, the Government established the Sri Lanka Engineering Services Division (SLES) under the Ministry of Public Administration and Management with the vision of a contended engineering service that would provide a better service to the country.

Today, administrative procedures of around 1440 engineering cadre positions in government sectors such as irrigation and water resources, railways, provincial engineering services of the nine provincial councils, Colombo Municipal Council (CMC), local government services, Buildings Department, Industrial Safety Division under the Labour Department, Government Factory, Coast Conservation Department, health sector, District Secretariats, all Ministries and other technical departments come under the purview of the SLES with equal conditions applied to all engineers in the public service, irrespective of the department in which they serve. But the actual number of engineers presently serving in the above government institutions is limited to 1115 and 325 key engineering positions are vacant.

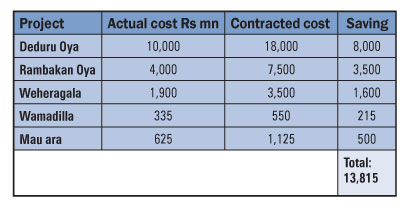

A significant amount of the country’s annual budget goes for development work where public service engineers are involved. During the 70 years since independence, especially the earlier half of it, there were several development projects that propelled the country’s development like the Galoya development scheme involving the largest and the most iconic reservoirs in the country and the Senanayake Samudra – a shining example of the country’s own engineering and financial resources being used towards its development. The costs incurred by the government on these projects were much less than what would have incurred if it had been done by local contractors, not to mention enormous costs of foreign contractors.

Proof of competency of the country’s engineers could be extended to a variety of other engineering works like the railway line extension works of Sri Lanka Railways, engineering works of the CMC, engineering design and construction works of the Provincial Councils, coastal protection works of the Coast Conservation Department, construction activities of the Government Factory, etc. These are besides the engineering works engaged by engineers of the Ceylon Electricity Board, Water Board, semi government sector which do not come under the SLES framework.

With that, it seems, the “golden era” of the public services engineers being the backbone of the country’s modern day development history has come to an end. We are now in an era where public service engineers are often sidelined from the country’s major development works and reduced to being just signing mechanisms for certifying completion of works for turnkey projects outsourced to third parties.

Mega projects worth billions of rupees, on EPC – Engineering, Procurement and Construction – basis are being outsourced to foreign contractors. Ironically the country’s engineers working for local subcontractors of these foreign main contractors now enjoy much higher perks and salaries than their counterparts in the public service sector.

At stake are government mechanisms for ensuring responsibility and accountability such as government estimations, procurement process, technical evaluation and tender boards, government supervision and quality assurance, feasibility studies, engineering planning and design, payment recommendations, engineering services, engineering administration and engineering management which could not be outsourced without compromising on responsibility and accountability of the government.

The organisation structure of the SLES as it is now, in some cases, encourages subversion of good practices by assigning less assertive junior engineers to environs in which they can succumb to outside pressure in certification of engineering works of private contractors.

Public service engineers are today without mandatory seats in key government mechanisms, yet responsible and answerable ultimately for any project failure. In contrast, those for example of the accounting profession with sole discretion of making payments to private contractors but with no part in the risk of the consequences of works failure have their due mandatory seats in those mechanisms. The situation is further aggravated by posts held by most engineers being not Management Service Department-approved posts and hence without perks enjoyed by posts of similar hierarchy in other professions. Thereby most of the qualified engineers are reluctant to join the government service where only the responsibility is given without due benefits granted to them.

Reminiscing the engineering successes of the early post- independence era, one is reminded of the country’s engineers being in the forefront of the nation’s effort towards development and prosperity of its people; Eng. D.J. Wimalasurendra in the hydropower sector, Eng. B.D. Rampala in the railways sector, Eng. A. J. P. Ponrajah in the irrigation sector and Eng. (Dr.) A.N.S. Kulasinghe in the civil engineering sector being icons among them. Their works were recognised and celebrated by the state and most importantly and wholeheartedly by the country’s people for the positive and balanced economic and social impact they brought. But one could perceive a huge gap since then of such recognition or celebration of engineers’ contributions especially by successive governments which came and went thereafter.

Naturally questions that arise are, are the country’s engineers now not competent enough, despite history revealing otherwise, to meet the challenges of mega development projects? What of the ensuing compromise on government responsibility and accountability in the present day outsourcing concepts practised? While there is nothing wrong in outsourcing engineering works, especially if it’s associated with conditions for foreign funding, aren’t there better alternatives that retain adequate control over monitoring, supervision, quality assurance, etc? These were the questions that emerged at a brainstorming session of a recent discussion at the Institution of Engineers, Sri Lanka (IESL).

The difficulties in recruiting and retaining engineers in public engineering service is riddled with such core issues on top of many other long standing issues of the sector. Extremely low salaries and privileges compared to other sectors despite the heavy responsibilities and difficulty of recruiting and retaining leading to shortages and overloading existing engineers without compensatory payment have plagued the sector for long without remedies from authorities.

The spotlight is thus on the SLES division which was established with the vision of a contended engineering service. The call for a full rethink in the processes of the division is very clear if the engineers in the public services are to avoid the professional abyss they are headed towards due to the present trend in policies of the skewed and unbalance socioeconomic development process. The IESL being the apex professional body for engineering profession in the country for its part cannot absolve itself of the responsibility if that is the predicament that befalls the public services engineers engineering profession.

(The writer is the Chairman of the National Policy Forum of the IESL. He is a Chartered Civil Engineer and member of the IESL Council. He can be reached at: mg_hdra@yahoo.com)

Work of local irrigation engineers without foreign involvement