John D’Oyly’s ‘fake news’ campaign and the fall of the Kandyan Kingdom

Signing the Kandyan Treaty at the Magul Maduwa (Audience Hall) in Kandy: Illustration from Ehelepola Somaratna’s translation of D’Oyly’s book

British rule in the Kandyan country was as incompatible as yoking a buffalo and a cow in the same plough.” This view expressed by a subordinate Kandyan chief was related by a British officer who appeared before a Select Committee of the British Parliament on Ceylon which sat between 1849-1850 to inquire into the grievances of people of Kandy and the omissions by officials of the British Government in Ceylon.

The simple analogy drawn by a person resident in the Kandyan Provinces in the early part of the 19th century is quoted by historian Tennakoon Vimalananda in his book ‘The Great Rebellion of 1818: The Story of the First War of Independence and Betrayal of the Nation’, and it speaks volumes of the incompatibility of the relationship between the inhabitants of the country and its colonizers. With the signing of the Kandyan Convention in March 1815, the British rulers expected a smooth transfer of power to their hands and for the locals to fall in line with their rules and regulations but less than two years later, a bloody rebellion led by some of the very chieftains who were signatories to the convention, left thousands of native people dead and the fertile lands of the Kandyan provinces plundered and laid waste by the military might of the colonizers.

As Sri Lanka celebrates 70 years of independence from British rule today, a month shy of the 203rd anniversary of the signing of the Act of Settlement of the Kandyan Kingdom better known as the Kandyan Convention, the Treaty signed on 2nd March 1815 remains a subject of intense scrutiny and interest in the country.

Gananath Obeyesekere, Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at Princeton University in his book titled ‘The Doomed King – A Requiem for Sri Vikrama Rajasinha’ released last year divulged in detail how the spread of ‘fake news’ by the British master spy on the island John D’Oyly led to the unceremonious dethroning of the last King of Kandy and cleared the way for the signing of the Treaty.

“Once Ceylon became a Crown Colony (in 1802, the coastal districts of the island were ceded to the British from the Dutch by the Treaty of Amiens entered into by the warring European powers) it was clear that there was no room for two monarchs to rule over the island. It had to be either the British Monarch or the King of Kandy. Hence they (the British) set about to remove the King in a very efficient way but it took them a long time to achieve their goal,” said Professor Obeyesekere.

Having failed disastrously in 1803 to invade the Kingdom of Kandy, their attempt repulsed by the natives who used guerrilla tactics and put their intimate knowledge of the terrain to best use, the British adopted different tactics to bring the Kandyan provinces under their rule.

Prof. Gananath Obeyesekere

The man who drafted the Act of Settlement, John D’Oyly had come to Ceylon in 1801 during the tenure of Governor Frederick North. He was among a number of British colonial officials who were recruited to serve on the island to be trained to integrate with the locals by learning their language as well as their customs. Eleven years later, Robert Brownrigg arrived in the country as the new Governor and working together, the two men pulled off a ‘constitutional coup’ of sorts ensuring that the Kandyan chieftains sign away their sovereignty to a foreign power.

Professor Obeyesekere says Brownrigg’s dismantling of the Kandyan Kingdom cannot be understood apart from the work of D’Oyly who during Thomas Maitland’s (Governor of Ceylon 1805-1811) tenure had become the “chief translator” or in other words the ‘chief spy’ and was “ in full form by the time Brownrigg arrived on the island.”

Brownrigg’s contempt for Raja Sinha as well as the Kandyan people becomes apparent from the correspondence he sent to Earl Bathurst, Secretary of State, said Professor Obeyesekere. In a letter dated March 15, 1813, the Governor refers to Raja Sinha as having a “tyrannical” disposition while of the Kandyan people he shows even more contempt saying, “their treachery and cunning is such that appearances are never to be relied upon” and they remain “contemptible as a military power.”

The coming together of D’Oyly and Brownrigg sealed the fate of Sri Vikrama Raja Sinha. Aided by Ehelepola who was the First Adigar as well as others in the Kandyan provinces who had grown weary of the Kandyan King, D’Oyly built up a spy network not only to fill him in on developments within Raja Sinha’s inner circle but also to spread stories discrediting the King.

Raja Sinha’s downfall came on February 18, 1815 when the unfortunate monarch was captured, plundered of his valuables and dragged away to be eventually banished to India.

Less than a month later, D’ Oyly had ready the Official Declaration of the Settlement of the Kandyan Provinces. At what was described as a “solemn conference” held at the Audience Hall (Magul Maduwa) of the Palace of Kandy, Governor Brownrigg, on behalf of his Government and the Adikars, Dissaves, and other principal chiefs of the Kandyan Provinces on behalf of the people” signed on the dotted line ceding the Sinhala Kingdom to the British Crown.

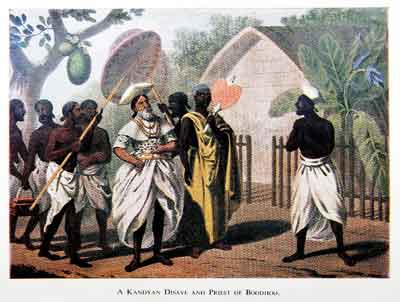

Illustration from John Davy’s book ‘An account of the Interior of Ceylon and of its Inhabitants’

The Official Bulletin sent by the British Headquarters , Kandy on March 2, 1815 states, “A public instrument of treaty, prepared in conformity to conditions previously agreed on, for establishing His Majesty’s government in the Kandyan Provinces, was produced and publicly read in English and Cingalese (Sinhalese), and unanimously assented to. The British flag was then for the first time hoisted, and the establishment of the British dominion in the Interior was announced by a royal salute from the cannon of the city.”

Article Five of the Treaty declaring the “Religion of the Boodhoo (Buddha) inviolable” and the promise to maintain and protect its rites, Ministers and Places of Worship’ was the saving grace which the Sinhala Chieftains had insisted upon if they were to put their signature on the document. But, as expected, there was opposition from the Christian elements particularly ‘missionaries.”

Gamini Iriyagolle writing on the Kandyan Convention- A conditional Treaty of Cession between the Sinhalese and the British, cites a letter dated March 15, 1815 in which Governor Brownrigg explains to his Government why the condition relating to Buddhism had to be in the Treaty. “The 5th confirms the superstition of Boodhoo in a manner more emphatical than would have been my choice. But as the reverence felt towards it at present by all classes of the inhabitants is unbounded and mixed with a strong shade of jealousy, and doubt about its future protection- and that in truth our secure possession of the country hinged upon this point. I found it necessary to quiet all uneasiness respecting it, by an article of guarantee couched in the most unqualified terms,” Brownrigg wrote.

While in the immediate aftermath of the signing of the Convention there was an uneasy co-existence between the two sides, it was short-lived. By 1817, the majority of the Sinhala Chieftains were up in arms, small disturbances snowballing into full blown rebellion which lasted almost a year. The Uva-Wellessa rebellion as it came to be known, was put down by the British in the most brutal manner.

John Davy, the army surgeon and physician-in-attendance to Governor Brownrigg between 1817 – 1819 in his “An account of the Interior of Ceylon and Of its Inhabitants” published in 1821, makes little effort to hide the brutality with which the rebellion was put down by the British. “The loss of the natives, killed in the field or executed, or that died of disease and famine, can hardly be calculated; it was, probably, ten times greater than ours, and may have amounted, perhaps, to ten thousand,” he wrote.

Other British writers too have recorded the brutality of the British military campaign with Sir Archibald Lawrie who served as a Judge of the Supreme Court in Ceylon 1892 writing that the “story of the British rule in the Kandyan country during 1817 and 1818 cannot be related without shame.”

While the colonizers overcame the local inhabitants by the use of superior forms of military ware to quell the rebellion, what was lost was their inability to enforce the terms of the Treaty in its true spirit.