Sunday Times 2

Cultural heritage, peace and reconciliation

Keynote speech delivered by Gamini Wijesuriya a renowned heritage expert from Asia at the Scientific Symposium, “Heritage and Democracy” of the International Council of Monuments and Sites from December 8-15 in Delhi

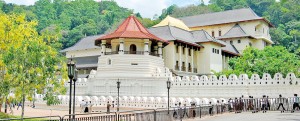

In 1998, the Dalada Maligawa, in Kandy was attacked by the LTTE

Like the trouble you have taken, we undertook to host the 10th General Assembly of International Council of Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) in Sri Lanka during this time. It was held at a time when democracy was threatened in this part of the world by a chain of events of which heritage was also a victim. India lost her Prime Minister in 1991 and just four months before the General Assembly (in May 1993), Sri Lanka lost her President. Both were democratically elected leaders killed by terrorists. The incident in Sri Lanka severely affected the General Assembly and some of the members opted not to attend. While that is not my focus today there is a link, and it might help explain my apprehensions and huge sense of responsibility on being invited to talk about the concept of ‘democracy’ as a conceptual framework with which to shape future heritage practices, a term and concept that has been used and abused since society began.

In 1998, the Temple of the Tooth Relic was burned by the same terrorist group the LTTE. Some of the ICOMOS senior members may remember they had the pleasure of visiting this temple, enjoying the annual procession which is Asia’s most stunning and spiritual cultural events. The temple is the most sacred Buddhist place in this country. Indeed this was perhaps the most, very first dramatic case of a World Heritage Site being targeted by terrorists.”

Albeit the destruction was unprecedented in scale and significance for the Sri Lankan people, it also proved a benchmark for disaster for being a springboard for peace thanks to heritage being understood as a special place where peace and security can be pursued. Indeed the division and conflict between the community groups which the terrorists so desired never happened. Community engagement and the rebuilding of the temple became a defiant symbol that such targeted attacks would not achieve the objectives sought by terrorists. Moreover, it influenced heritage practice thereafter.

Since then however we have witnessed further attacks on heritage sites worldwide: Including the World Heritage List: damage to Preah Vihara in Cambodia, to the Mausoleums of Timbuktu in Mali and attacks at the Bodhgaya to name a few. Targeted and collateral damage to heritage in the Middle East continues. As much as we are concerned with these edifices being destroyed, the more vexing issues that should draw our attention is another. It is the impact on the social fabric and the community identity that we need to address.

According to the current UN Chief, “We are a world in pieces. We need to be a world in peace”.

It is therefore not only reasonable but imperative that the heritage sector embraces the ‘Role of Cultural Heritage in Building Peace and Reconciliation’ as a theme meriting more research and capacity building to consolidate necessary knowledge areas and skills set under the wider leitmot of ‘democracy and heritage’. Needless to say this is a direction that is all the more strongly linked to politics in its more rudimentary form (‘who gets what, when and how’) and both ‘democracy’ and ‘heritage’ are contested territories.

UNESCO – created at the end of the Second World War – stated in its constitution: ‘Since war begins in the minds of men and women the edifice of peace must be constructed’. Aimed at building a world at peace, UNESCO has developed many normative instruments and policies. In the recent past much emphasis has been placed on the role of heritage in building peace and reconciliation in the midst of recurring threats to heritage.

There is much progress ranging from general policy work such as the “2015 World Heritage and Sustainable Development Policy” to milestone decisions such as that of the International Criminal Court regarding destruction of cultural property in Mali.

UNESCO ‘2015 World Heritage and Sustainable Development Policy’ contains a section on the use of heritage for promoting peace and reconciliation.

Other initiatives include the 2015 “Strategy for reinforcement of UNESCO’s action for the promotion of culture and the promotion of cultural pluralism in the event of armed conflict.” This strategy covers all aspects of culture and includes in its objectives the mainstreaming of a concern for culture in humanitarian, security, peace keeping and peace building policies and operations.

The work done within the UNESCO has led to a new international awareness of the importance of culture as a humanitarian and security issue, which resulted in a series of landmark resolutions taken at the highest level, including by the UN Security Council.

The protection of cultural heritage is included within the mandate of the UN peace keeping Mission in Mali.

Some of the messages shape heritage management practice on the ground even more directly. The Post Disaster Needs Assessment methodology is a case in point. It considers not only the damage to physical assets, but also the implications in socio-economic terms and in general the larger human development impact of a disaster resulting from its effects on the cultural sector and on heritage in particular.

There are other initiatives, notably ICOMOS Norway’s work with the World Heritage Centre IOCOMOS, International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), International Centre for the study of Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) known as our Common Dignity has helped to identify the diversity of rights issues experienced in the world heritage sites and the effort mobilised to start resolving them equitably. The report launched at this General Assembly points to issues involved and actions needed.

Furthermore, attempts are being made to use heritage destroyed in the past as symbols of peace and reconciliation and for healing processes, exemplified by cases such as Mostar, (Bosnia and Herzegovina) and Hiroshima (Japan). Other examples include the reconstruction of the Mausoleums of Timbuktu. The Joint Technical Committee on cultural heritage established in Cyprus, a bilateral project for the rehabilitation of cultural heritage properties as a confidence building measure is another example.

Such an encouraging overview could bolster us into thinking that, collectively and institutionally, we are doing rather well on these themes. Is this true? Are such approaches sufficient? I argue that there is a major stumbling block ahead of us in the heritage sector since this new arena requires a mind-set which is alien for entire generations of heritage practitioners. Let me explain.

Peace and reconciliation are all about people but in the heritage sector we are shareholders of a discourse that has forgotten people. The idea of heritage as developed in the west in the 19th century looks at heritage from the point of view of the historian. ie. For its ability to carry information about the past and for its aesthetic qualities. I have elsewhere called this secularisation. When something is declared “heritage” in this approach ipso facto it is removed from ordinary life and placed on an intellectual meta-level. People themselves or their aspirations have not been seen as important. The heavy reliance on this discourse for me is the problem.

Let us take an example. Reconstruction is a very popular theme these days. After the Sector World War, people in Warsaw celebrated the town’s reconstruction as expressed in this poem by Zofia Piotrowska of in 1962:

You rose from ruins and disease, Warsaw

You rose from ashes and mist

You rose through the labour of all the Nations

You rose through the will to exist

But two years after in 1964 the “experts” agreed on principles creating a widespread apprehension and at times hostility towards reconstruction. Yet “reconstruction” is part of a recovery process from shattered lives and livelihoods. It addresses the needs and aspirations of the communities affected by conflict and is the current global practice and any types of interventions are only academic.

This is just one of many cases. The key point is that disregard for traditional knowledge systems and maintenance practices embedded in community needs is another instance of distancing people from heritage and undervaluing continuity.

Overlooking the people factor has led to marginalisation, isolation and snubbing the views of the people. Ever- expanding definitions of heritage today, their power in making or breaking identities, concern for multiplicity of values, layers of history, layers of stakeholders, layers of communities have not have not been accounted for when constructing heritage narratives.

Blaming the western conservation discourse may seem all too easy. But it is not without good reason either. The words of the current president of ICOMOS, Gustavo Araoz, reminds us that this discourse was only challenged after one and a half years despite many criticisms. Referring to the impact of Nara document, “Nara shattered once and for all long-held Eurocentric insistence that there were long held cultural principles for heritage identification and treatment”. It took so long because, heritage practitioners assumed that they have a good understanding of heritage without rightful owners- people.

Despite, these difficulties there have been many moves to place people at the centre of heritage over the last decade and recognise that the heritage places we talk about are those created by the people, for the people and cared for by the people who are thus an integral part of heritage.

This shift, which must be called an ‘alternative heritage discourse’, promotes a different approach and does not lend its self to universal recognition since – by definition – each heritage place belongs to and is meaningful for those who created it and for those who continue to use with added values. This approach recognises the contested nature of heritage, whereby a different group within a community could have a completely different vision of what is important and why. It is this heritage debate which is important to recognise for the purpose of making peace and reconciliation.

However when placing people at the centre, we are confronted with a different set of issues to those that are familiar to heritage practitioners such as decay of materials, interventions and authenticity. The new issues are:

- the political context of heritage;

- the social role of heritage including livelihoods;

- constructing inclusive and widely constructed heritage narratives;

- rights and knowledge issues;

- building community resilience through heritage;

- recovery from conflict situations.

Above all, meaningful decision making at the heart of the communities is fundamental to address every one of the key issues. They all pose a set of challenges unfamiliar to heritage practitioners.

We cannot be naive and assume that people at all levels carry homogeneous views on any issues, let alone heritage. For this and many other reasons, when dealing with many issues one has to deal with conflicts. We have a huge responsibility as heritage practitioners.

It is here that the concept of democracy can be best embraced by our sector. Despite inherent deficiencies, it is widely believed that democracy can improve the quality of decision making. It is known for its ability to deal with conflicts and differences, and to promote equity and justice. Inclusiveness, rights to participate, considered judgements, informed decisions, transparency are some of the other democratic qualities.

Despite these we cannot be over optimistic. Let us take the example of Dresden Elbe Valley World Heritage site in Germany. This was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2004 as a cultural property deemed to have Outstanding Universal Value. A controversy arose when the authorities decided to build a bridge across the river which forms part of the landscape of the World Heritage site. In a referendum, the residents voted for the construction of the bridge. As a result of this, it became the first cultural site to be deleted from the List in 2009. (http:// whc.unesco.org /en/list/1156). The reason given was that the bridge was negatively impacting the outstanding universal values of the site. It is possible that, with more information on the implications of the new bridge for the historic landscape, the people of Dresden might have a different choice. But it is also possible that they would have decided to have the bridge anyway. Was the real problem a poorly-designed bridge? This paradox shows that there is no perfect solution that democracy saves, nor does it resolve our ideas of where heritage values lie. (the OUV of a site as recognised by a Committee.)

At the time of the reactive monitoring mission to Kathmandu Valley, people linked to Bouddhanath temple had already discussed, reconstructed and started the lost part of the stupa regardless of the wishes of the old international community. Such democracy – will and I say should – remain.

There is also a potential danger of trying to generalise and apply democratic principles naively. In the name of some of the democratic principles such as equity, gender balance and internationalisation of heritage, there is a tendency, for heritage professionals to question cultural practices, such as access to women and those of another religion. Where should we draw the line?

To conclude, in my opinion we are looking at a paradigm shift where the focus moves from the wellbeing of both heritage and society. This promotes people-centred approaches as a way forward and as the means to adjusting and adapting our approaches to meet the real needs of society and its heritage. This is a shift through which we can, in turn, harness the full potential in cultural heritage in building peace and reconciliation. We have to recognise with a certain honesty the pressing need to promote this shift also within the heritage community, specially those who are defiant. We must be prepared to challenge the entire conceptual edifice of heritage conservation, starting, for example, with the so called “experts” if we are to be successful. Indeed ‘expert’ is the first word we should perhaps sacrifice in the name of democracy, peace and reconciliation.

In embracing a new approach, we may have to let go or revisit many things that have current mythological status including the concept of heritage itself. We need to open our minds and also look beyond the heritage sector in order to embrace an alternative discourse effectively. A rich variety of presentations lined up under this theme will allow us to track efforts being made globally towards this goal. Hopefully these inputs will come together as a springboard for new forms of awakening but also reconciliation within the heritage sector itself. And maybe the use of the word ‘democracy’ in our sector will take on clarity that makes me very comfortable with it!