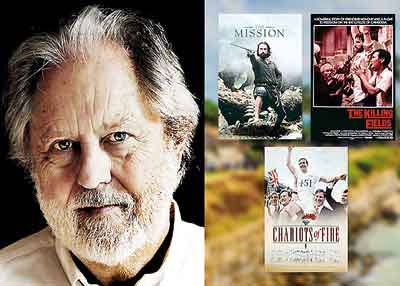

Lord David Puttnam: From award-winning film maker to policy maker

View(s): In the summer of 1978, Lord David Puttnam was ill and housebound in Los Angeles when he came across a book that would change his life. Its title – decidedly undramatic – was “An Approved History of the Olympic Games” by Bill Henry. But the film that Puttnam would be inspired to make after reading that book would be another creature altogether – released in 1981, “Chariots of Fire” was full of drama and striving, and would inspire a generation of filmmakers and audiences.

In the summer of 1978, Lord David Puttnam was ill and housebound in Los Angeles when he came across a book that would change his life. Its title – decidedly undramatic – was “An Approved History of the Olympic Games” by Bill Henry. But the film that Puttnam would be inspired to make after reading that book would be another creature altogether – released in 1981, “Chariots of Fire” was full of drama and striving, and would inspire a generation of filmmakers and audiences.

Puttnam would later recall: “On page 116, the author writes of three sensational wins by British athletes’ at the 1924 Paris Olympic Games and it was the story of two of these – ‘long-legged collegian’ Harold Abrahams and ‘dark horse’ Eric Liddell, a religious man who refused to run on a Sunday – that eventually formed the basis (with some dramatic licence) of Chariots of Fire.”

In the years after “Chariots of Fire” became a runaway success, Lord David Puttnam would be faced again and again with how his audience was divided between its two protagonists Eric Liddell and Howard Abrams.

“The film offered the opportunity to look at two sides of the human character,” he told journalists.“Both involved winning but winning for different reasons and through different means. And so I’ve had people come up to me and say, “Oh I really loved that film about the Jewish runner” and they wouldn’t mention Liddell at all. And others would talk about Liddell and his principles and everything else. So people carved out the movie for themselves.”

It was also clear to Puttnam that the movie’s appeal came from a nostalgia for when sport was clean and competitive and not tainted by drug use.Puttnam would describe it as a longing for a time when sport was just about excellence.

In as much as the film proved influential in the lives of audiences around the world, it changed Puttnam too. It contributed, along with movies like “The Killing Fields” “Midnight Express”, “Memphis Belle and “The Mission”, to his reputation as one of the most successful film producers of all time. In total he won 10 Oscars, 25 Baftas and the Palme D’Or at Cannes for his work in movies.

Among the many he made, his personal favourite is the lesser known “Local Hero.”Puttnam considers it his most personal film, because he lived in Ireland in exactly that kind of environment; embedded in a small village, and surrounded by a tightly knit community.

Local Hero tackled the issue of the environment, decades before eco-friendly became a buzzword, reflecting Puttnam’s early commitment to being an eco-advocate. “It always has been that way for me. When I was making that film, I was also president of an organisation called – it’s a terrible title – the Council for the Protection of Rural England, and I was also chairman of the first committee that got the bill for climate change legislation in the world. We had the world’s first climate change act,” he told Today Online.

Puttnam received his knighthood in 1995 and retired from film production in 1998 to focus on his work in public policy as it relates to education, the environment, and the creative and communications industries. He has never regretted the move:

Puttnam received his knighthood in 1995 and retired from film production in 1998 to focus on his work in public policy as it relates to education, the environment, and the creative and communications industries. He has never regretted the move:

“I genuinely believe that education is the most important ministry of all. Without education, nothing else works. If you haven’t got a good education system, everything else collapses. You can’t develop a health service off the back of a poor education system. You can’t guarantee yourself a decent pension off the back of a bad education system. Or even infrastructure. It’s the signequ’on of a successful society.”

Today, he sees his legacy as being divided equally between the wonderful films he helped make, and the policy reforms he drove in his time in government. When asked what he wants on his epitaph, he says simply that it should read: “God knows he tried”.