The sacred art of Temple Food

Nun Hong Seung explains the art of Temple food. Pix by Namini Wijedasa

In a well-lit hall, a cluster of women sit at tall benches lined up with raw vegetables and seasonings. Some are taking notes. And all are listening intently to a serene Buddhist nun who, at the front of the room, is teaching them how to cook.

But there is something different about the ingredients they will use. Not only are there no meats, fish or eggs. There isn’t an onion in sight. No leek, garlic, chive or scallion. This is a ‘Korean temple food class’ and everything must be prepared without the five pungent vegetables.

In recent years, with a surge in veganism and vegetarian eating, Korean temple food has become more popular. This prompted the opening in 2015 of a centre in Seoul to educate the public and to promote this healthy cuisine that originated in Korean temples and has been handed down through generations.

A model of a temple kitchen

In Korean Buddhism, the art of eating meals is called ‘Baru Gongyang’ which means ‘offering’. Korean Temple Food Centre literature calls this a sacred ritual through which we reaffirm our intentions and vow to live a Bodhisattva’s life, reflect on the Buddha’s teaching and the services and graces of all Bodhisattvas, nature and sentient beings. Meals must be consumed in silence and humility.

In a formal monastic meal–which lay people can now experience in temples and speciality restaurants–food is eaten off wooden bowls. First, participants pay homage to and praise Buddha, the Bodhisattvas and Buddhism’s Three Jewels: the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. They then hold the bowls in both hands and chant: ‘Through this meal offering, may all sentient beings regard the joy of Seon (Zen) practice as their food and be filled with the joy of Dharma.’

Finally, they recite the ‘Verse of Five Contemplations’: ‘We reflect on the effort that brought us this food and consider how it comes to us. We reflect on our virtue and practice and whether we are worthy of this offering. We regard greed, anger and ignorance as obstacles to freedom of mind. We regard this meal as medicine to sustain our life. For the sake of enlightenment we now receive this food.’ These codes are inviolable.

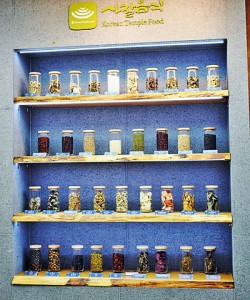

A selection of dried roots, shoots, seeds and leaves

Regardless of one’s social or monastic standing, all participants sit together and share the food without any class distinctions, representing the idea that all people are equal. Each participant serves him or herself, to ensure cleanliness. Each person takes only as much as he or she can eat and no food is left. The water used to rinse the bowls is drunk.

‘Baru Gongyang produces absolutely no food waste, acknowledging the limits of nature’s bounty and the importance of environmental protection,’ the Temple Food Centre states. To create a sense of harmony and solidarity, everyone shares the food produced from the same pot at the same time.

The food is vegan. This, it is explained, is because the first t precept of Buddhism is to not kill. Buddha said in the Nirvana Sutra, ‘Eating meat cuts the seed of compassion.’ Vegetables of the onion family are prohibited as it is said consuming these will increase lust. Eating raw food, meanwhile, will increase anger.

The seasonings are natural. They include ground mushrooms, ground kelp, ground sesame and ground raw beans. These are used to make soup, kimchi and side dishes. Food preservation is a key component of Korean temple food. Kimchi, doinjang (soybean paste), gochujang (red pepper paste), ganjang (soy sauce), jangajji (pickled vegetables), chojeorim (vinegar-pickled vegetables), sogumjeorim (salt-pickled vegetables) and jangjeorim (pickled vegetables in pot) allow ingredients to be kept without a loss of nutrients.

Vegetarian Korean pancakes and crumbed bean curd

“Temple food treats cooking as a path towards enlightenment,” says Nun Hong Seung from the Baekryeon temple in Kangjin, who is conducting the class.

“Everyone must learn to cook it. Temple food has a unique taste. It is not fancy, it not loud or showy. It is simple, like temple life.”

| Food for the seasons | |

| Food for the winter solstice: White radish jangaji (pickle), cinnamon punch, gyeongdan (rice ball cake), red bean porridge and radish water kimchi. Good food for a cold: Deodeok jangaji (a root pickle), white radish jangaji (pickle), stir-fried dried radish greens, kimchi bean sprouts porridge, neungi mushrooms soup. Food for New Year’s Eve: Shitake mushroom with white radish jorim (simmered dish), yaksik (sweetened rice with dried fruit and nuts), white radish namul, kimchi dumpling and japchae (glass noodles). Raw food: Pine nuts, Chinese matrimony vine, non-glutinous rice and glutinous rice, pine needle powder, honey, black bean, chestnut, sweet potato, jujube (Chinese date), green laver (seaweed). Food for Buddha’s birthday: Water parsley ganghoe (blanched), glutinous rice cake, parched beans, shredded white radish, water parsely bibimbap (mixed rice) and spinach doenjang (fermented bean paste) soup.  Good food for a cold  Food for Buddha’s birthday  Food for the winter solstice  Food for New Year’s Eve |

(The writer’s visit was sponsored by the Korean Culture and Information Service to mark the 40th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Korea and Sri Lanka).