Churning and chasms: Findings from livelihoods research in post-war Sri Lanka

From 2011-2016 the Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) implemented a series of qualitative and quantitative studies to understand the dynamics of livelihood recovery in fragile and conflict affected countries. The Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) implemented the studies for the Sri Lankan leg of the project, and the findings provide important departure points for the ongoing process of post-war economic development.

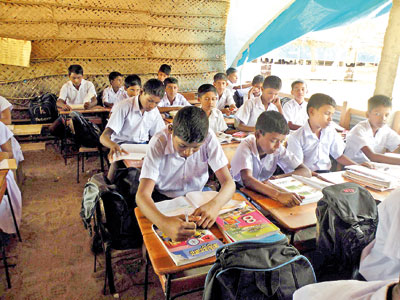

File picture of children at a northern school.

The research, in particular, was triggered by a curiosity to understand how people had made a living during conflict, and what the trajectory of livelihood recovery looked like in post-conflict situations. Indeed, the research confirms much of what is increasingly clear to those observing post-war Sri Lanka; that the assumption that livelihood recovery naturally follows the end of conflict is not necessarily true.

Over 2500 persons were interviewed in the North and the East in two phases, first in 2013, and second in 2016. What was broadly noted was a high level of ‘churning’. Churning refers to a phenomena by which change can be seen in all directions. Therefore, while some households may see an improvement, relatively equal numbers may see their situation worsen. In Sri Lanka there was not only high rates of churning but also the curious occurrence in which some households that had been doing well during the first phase of the project, suddenly finding themselves significantly worse off. This is due to an intersection of factors, those that occur due to the situation of conflict, some stemming from situations of sustained poverty, and others from long-standing socio-economic reasons. It is impossible to fully understand post-war Sri Lanka without acknowledging the multidimensional experience of poverty. This article looks at three particular findings that make up a much larger picture.

One particular finding connects to asset ownership. A general increase in asset ownership was recorded between the two phases. When this increase is unpacked, however, something striking comes to light. A household may be considered as better off when they own more assets, and own assets not typically owned by others in the community. The question of how the assets were acquired then arises. As an example, one of the studies noted the rapid expansion of credit markets and how the significant increase in assets in the area studied were in fact assets bought on credit. Some of this entry into debt is connected to a need to purchase basic items such as food and healthcare. In Sri Lanka, however, households were found to frequently buy bulk items (like petrol -powered machinery, vehicles, refrigerators and fishing equipment) on credit. Over 40 per cent of households stated that the item was procured either through a loan or some form of credit. What is particularly interesting is that the choice of increasing their assets through credit is intimately related to their lack of confidence in the security situation. Whilst the households surveyed acknowledged that physical hostilities had ended, they do not entirely perceive themselves to be safer. Future policy making may be well advised to consider this connection between a reduction of conflict and the opening up of credit markets.

Cases of debt are high in many households. Sri Lanka records one of the highest levels of sustained debt amongst the countries studied under the SLRC project, with more than half the respondents indebted in both phases. In the first wave, 69.3 per cent of respondents noted that someone in their household was in debt, in the second, this number reached 70.3 per cent. A percentage of 54.7 was then always in debt, and 15.7 per cent went into debt between 2013 and 2016. Such borrowing is done through both formal and informal lenders. CEPA studies note that much of this may be due to the combination of increased demand for credit, continued exposure to consumerist lifestyles, and also poor management of finances. However, this can lead to further food insecurity, and a previous CEPA project noted that households tend to cope with increasing indebtedness by compensating in terms of the quantity, quality, and frequency of meals. As such, cycles of precarity and insecurity almost organically manifest themselves.

The studies also note the lack of state support for livelihoods in those areas that had been impacted by the conflict. Less than 23 per cent of households reported receiving social protection services through a government agency. However, the studies do note an increase in the number of Samurdhi recipients between 2012 and 2015. Much of this is due to the fact that Samurdhi coverage only extended to the war-affected areas after 2009. There are variations in receipt in terms of district. Mannar saw the largest increase in beneficiaries, – 50 per cent, whilst Jaffna recorded the highest proportion of those not receiving Samurdhi in either phase of the project. What is important to note here is that the receipt of the transfer alone is not enough, but that the community engagement such as Samurdhi meetings, consultations and awareness programmes that took place between 2012 and 2015 allowed for a more positive association. A respondent with knowledge of a meeting on social protection was more likely to have received assistance, as the access to the network allows the recipient to benefit from multiple forms of support. However, given that the amount given is nominal, and is divided amongst extended family members, its ability to alleviate poverty, especially against rising costs of living is an issue requiring attention.

This article draws attention only to a microcosm of the findings from the Livelihoods project. Other studies, which require more sustained analysis, point particularly to issues of patriarchy, patrony and exploitation that also continue to affect livelihood recovery in post-war Sri Lanka., The SLRC studies in their totality underline the necessity of an intersectional approach to economic development.

(WALK the LINE is a monthly column for the Development Page of the Business Times contributed by CEPA, an independent, Sri Lankan think-tank promoting a better understanding of poverty related development issues. CEPA can be contacted by visiting the website www.cepa.lk or via info@cepa.lk)