They dared to venture out with camera in hand

View(s):Ismeth Raheem writes on three pioneering Victorian era women photographers who made their mark in then Ceylon

Julia Cameron

The role of women in the world of 19th Century photography was a very rare phenomenon. Although such participation is not recorded elsewhere in Asia or Australia, Sri Lanka ( Ceylon) fortunately was an exception to the rule.

Photography and the Victorian Age commenced almost simultaneously. The invention of photography and the coronation of Queen Victoria happened within a few months of each other.

In Britain and France, where photography was first pioneered, the situation was markedly different. Several of the earliest female photographers were married to male pioneers. Constance Fox Talbot – nĂ©e Mundy (1811â1880) married William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) in 1832. He was one of the key players in the development of photography in the 1830s and 1840s. She briefly experimented with the process as early as 1839 and has been credited as the first woman ever to take a photograph.

âThe Sinhalese Girlâ : A photograph by Julia Cameron

Male dominance is an undeniable feature even in Western society where it was exemplified by many stringently observed conventions and rules regarding the nature of work activity in Victorian society. In the midst of such an intolerant social atmosphere it is surprising to discover that in Sri Lanka, there were three female photographers active between 1860-1910. They were â Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879), Inez Maria del Tufo (1876-1956) and Ethel Mairet Coomaraswamy (1872-1952).

To their credit the three women had successful careers as photographers and their work earned them recognition among their male colleagues.

Photography over the Victorian period and up to the First War was a demanding medium even for men. It demanded considerable manual labour notwithstanding the physical discomfort and sheer weight and bulkiness of wooden brassbound cameras and equally heavy tripods that had to be coped with including the tricky issues of handling toxic chemicals used in developing and fixing images.

The technology at the time demanded the photographer had to use glass supports of varying sizes from the large and cumbersome (12X 14 inches) to medium size (9X6 inches). It was only in the late 1920s that modern materials; plastic roll film, which displaced glass mounts, lightweight cameras and tripods and easily operable equipment were available in the market.

The bulk of these materials in use by a 19th Century photographer had to be manually carried by âcooliesâ- an all male labour force. Transport was largely limited to bullock carts travelling on rutty tracks, which were supposedly termed as roads. The only exception was the rail link from Colombo to Kandy established in April 1867.

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832- 1898) better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, the English writer, mathematician, logician and Anglican deacon was himself a fine amateur photographer and described graphically the intricacies of managing the wet plate in his version of a photographer in âHiawatha Photographingâ in which he had used the metre of Longfellowâs The Song of Hiawatha.

âFirst a piece of glass he coated

With Collodion, and plunged it

In a bath of lunar caustic

Carefully dissolved in water-

Then he left it certain minutes

Secondly, my Hiawatha

Made with a cunning hand a mixture

Of the acid pyro-gallic,

And have glacial-acetic.

And of Alcohol and water

This developed all the picture

Finally he fixed his picture

With a saturate solutionâŠâ

In the tropics the problem for photographers was not just heat, rot and damp, more importantly shipping companies like P&O would not transport Collodion, a vital chemical for the developing process because the active ingredient was smokeless gun powder.

Inez Del Tufo with her son

For almost half a century after its invention in 1839 photography was only possible during the hours of daylight. It remained so until the advent of flash light photography in the 20th Century. Taking photographs outdoors meant arduous backbreaking work in the heat and humidity of a tropical climate. Only the bravest and staunchest of women would have pursued a career in photography under these trying conditions but these three female photographers overcame the formidable obstacles and earned their own secure place in the annals of the history of photography.

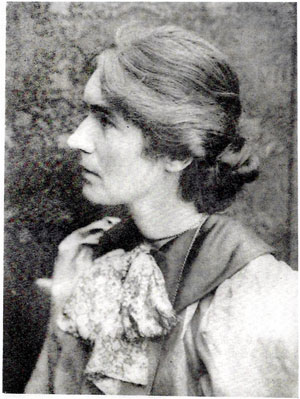

Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879)

Julia Margaret Cameron (nee Pattle), the celebrated English portrait photographer was born in Calcutta in 1815 and married Charles Hay Cameron (1795-1881) in 1838. Cameron was a distinguished legal personality both in India and Sri Lanka and is known for heading the Royal Commission better known as the Cameron âColebrook Commission in 1829 to propose much needed reforms which laid the foundation for the radical reforms in the civil, judicial and educational process that transformed British administration in Sri Lanka.

Returning to England in the early 1850s, the Camerons purchased a property in Freshwater, in the Isle of Wight next door to Farringford, the retirement home of Poet Laureate Alfred Lord Tennyson. The two-storeyed house christened Dimbola after one of her husband Charlesâs coffee plantations in Sri Lanka was both residence and studio for Margaret where she perfected her photography while the rest of the Cameron family was away in Ceylon.

It was here over a career that spanned 13 years that she photographed some of Englandâs âgreatest men and fair womenâ. These enigmatic portraits, which included some of the most eminent artists, writers, scientists and politicians in England propelled her to fame.

The couple then decided to be with their four sons amidst the family plantations in Ceylon. This was their final break from England. Julia sailed from Southampton, England on the S.S.Mirzapore on October 21, 1875 and arrived at Galle on November 20 accompanied by her husband Charles Hay Cameron and their fourth son Hardinge Hay Cameron (1846-1911).

Charles was 80 and Julia 60 years when they made their exit from Dimbola. Although not in the best of health, Julia was active in photography till her death in January 1879.

The bulk of Cameronâs work in the colony was focused on Sri Lankan and Indian domestic staff and labourers who worked on the familyâs various bungalows and estates and had an air of anonymity about them.

The only surviving example of comparable portraiture of her English admirers were the four studies of the celebrated Victorian botanical artist Marianne North (1830-1890) who made two visits to Ceylon.A close friend of the Camerons she stayed at the residence of Hardinge Hay Cameron at Kalutara. He was then both Assistant Government Agent for the district and Private Secretary to the Colonyâs Governor, Sir William Gregory (1817-1892).

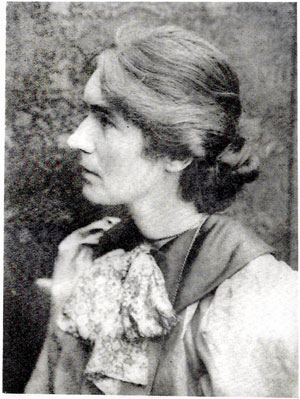

Inez Maria del Tufo (1876-1952)

In stark contrast, the Indian born Inez Maria Gibello (1876 – 1952) differed from the other two female photographers being the only female in the photographic trade in Colombo, which was dominated by males. Born in Kutch, India in 1876, her father was an Italian businessman and trader. In 1895 she married Innocenzo del Tufo, (1844-1912) born on October 7, 1844 in Aversa, Italy who supposedly had aristocratic connections. This was his second marriage and personal details of the first wife are unknown.

The firm advertised itself- Del Tufo & Co as âartists and photographersâ, and had branches in Mumbai (Bombay) in the 1880-90s and later in Brigade Road, South Parade, Bengaluru (Bangalore), Ootcamund, and in Mount Road, Chennai (Madras).

Ethel Coomaraswamy

The photographic firm had an intriguing logo, which may have attracted clients both resident and foreign-âPhotographers by special appointment to the King of Italyâ.

This connection added so much of leverage to del Tufoâs commercial photographic business. The firm also like other photographic studios of the period offered printing and developing facilities for their clients. It also provided another unique service, -âenlargements of all sizes from amateur negatives, finished with pencil and water colours.â In an age when colour photography was unknown, such hand coloured portraits were popular among residents in India and Ceylon.

Also another significant announcement in the advertisement was âCarpentry Department for Repairing and improving all photographic Instrumentsâ. A vital service for 19th Century cameras and tripods, which were largely made of tropical timbers and needed constant repairs and adjustments.

After their marriage in 1895 the couple decided to migrate to Ceylon from India and set up their photographic business by opening a studio in the proximity of the Galle Face Hotel, Colombo then an exclusive suburb of Colombo.

Colombo was a popular tourist destination for trans-oceanic passengers plying the Indian Ocean trade and route to the Far East and Australia. No doubt it was a clever business move by del Tufo and well timed. The earliest record of their commercial photographic firm is around 1902, operating a studio under the title Madam del Tufo, in 252, Colpetty Road, Colombo 1, next door to the Galle Face Hotel. In 1907 the firm had moved to No. 12, Colpetty Road, Colombo 3.

Later in 1914 the address of the firm is given as Madam del Tufo, Artist, Photographer and Proprietress ,Iceland Palace, Colpetty Road Colombo;and the firmâs name disappears from the records of the trade journals after 1930. Much of her work focused on family portraits and she photographed many of Ceylonâs urban elite.

Just before the Second World War around 1938 she visited her son Vincenzo del Tufo ([1901-1961), Deputy Governor, Malaya (Malaysia) in Kuala Lumpur. Tragically during the war, she was taken a prisoner and incarcerated in the notorious Changi prisoners of war camp when the Japanese overran Malaysia and Singapore – but returned to Colombo when the conflict ended. Inez Maria del Tufo died on April 10, 1952 aged 77.

Ethel Coomaraswamy (1872-1952)

Ethel Mairet Coomaraswamy (nee Partridge) was born in 1872, Barnstaple North Devon. First as a teacher 1891-1902 and from1890-1899 she undertook a serious study in music and was awarded the Royal Academy of Music teachers pianoforte in 1899. On her return to England in 1902 while hunting fossils in the north Devon coast she met Ananda Coomaraswamy and they married in June that year.

Born in Sri Lanka in 1877 Ananda Coomaraswamy was educated in England. After an illustrious career at the University of London he obtained a First Class in geology and botany in 1900.

In 1902 he was appointed as the first Director of the Mineralogical Survey of Ceylon and the couple arrived in Colombo in March 1903, and after four years of intense research and documentation left Ceylon in December 1907. She assisted her husband in their joint research of the techniques used by the craftsmen in the manufacture of jewellery, pottery, metal casting, steel making, embroidery, weaving, dyeing and other visual arts and crafts of the Districts of Kandy, Matale and Ratnapura. In the course of her work she exposed hundreds of glass plates to compile a detailed documentation and several of these photographs were converted to lantern slides which she utilized when she undertook teaching programmes for rural girls in these districts.

On their return to England in June 1907 the Coomaraswamys commenced work on their publication and by December 1908 the book Medieval Sinhalese Art was brought out as a limited edition of 425 copies.

All the art and printing work associated with the work was carried out in their workshop and home based at the Norman Chapel, Broad Camden, Gloucestershire, England.

Although the public perception of Medieval Sinhalese Art is associated with Ananda Coomaraswamy alone and not in partnership with his wife Ethel, undoubtedly she was the main contributor for the text on Sinhalese Music. Also the descriptive text for the finer details in Kandyan crafts like ivory and horn carvings, and other craft manufacture was based largely on her research.

Most importantly the majority of the plates published in Medieval Sinhalese Art were from the photographs she took while working in Sri Lanka. The unique contribution and participation of these three pioneering women photographers during their stay in Ceylon is almost unparalleled in the annals of the history of photography in Asia.