Sunday Times 2

The Noble Eight-Fold Path and the judicial process

View(s):With the National Law Week to be observed on a countrywide scale from November 23 to 29, we need to reflect on the fact that judicial service is one of the highest forms of responsibility for any individual. Every source of guidance regarding rules of human conduct relevant to this process needs to be examined.

An outstanding source of wisdom which can illuminate judicial responsibility is the vast repository of instruction concerning human conduct contained in the teachings of the great religions. Yet, these have been largely neglected in the past few centuries, owing to the growing separation between law and religion.

The purpose of this article and three more to follow is to outline the wonderful contribution religious thought can make to the wiser, more equitable, more humane and more understanding discharge of judicial responsibility. A start will be made with Buddhism, with its enormous wealth of teaching and its minute analyses regarding the workings of the human mind.

Likewise, Christianity, Hinduism and Islam are vast reservoirs of wisdom and inspiration relevant to judicial conduct, and an effort will be made to examine these in later contributions.

By C. G. Weeramantry, former senior vice president of the International Court of Justice

An area of deep relevance to the judicial function, which is as yet largely unexplored in the judicial context, is the teaching of Buddhism regarding the rules of righteous conduct.

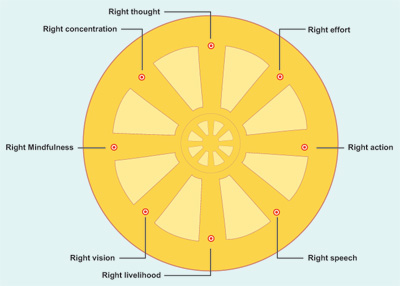

While the Noble Eight-Fold Path is looked upon primarily as a means to emancipation from suffering, it also sets out all-important guidelines for every aspect of human conduct. It is indeed one of the most comprehensive codes of human conduct ever compiled, and is therefore of particular relevance to the judicial process. It is strange that it has not thus far been specifically brought to the attention of the global judiciary as part of their training.

This gap needs to be bridged and this all-important guide to decision-making brought to the notice of judges worldwide. These rules of human conduct cover every aspect of human behaviour, both short term and long term, and whatever one’s profession or calling, they offer reminders of important aspects pertaining to one’s conduct. This applies in particular to judicial decision making, a function so important that it needs to be enriched from every available source of wisdom.

Let us look at four aspects of the Noble Eight-Fold Path — right thought, right concentration, right mindfulness and right vision.

Let us look at four aspects of the Noble Eight-Fold Path — right thought, right concentration, right mindfulness and right vision.

1. Right thought

Right thought has been deeply analysed in Buddhist teaching and includes concepts of detachment, helpfulness, concern for others and diligence. There must be an elimination of irrelevance, partiality, anger, jealousy and enmity. In the words of the Dhammapada regarding wrong thoughts, ‘In the unessential they imagine the essential – In the essential they see the unessential – Those who entertain wrong thoughts never realise the essence.’ (Dhammapada 1.11) Right thought means also the total banishment of cruelty and callousness.

A guardian of the law must abide by the law and act both lawfully and impartially (Dhammapada 19.2). The concept of right thought is expounded in detail in Buddhist writings which contain much wisdom relevant to the work of the judiciary. An analysis of this material from a judicial point of view has not been attempted and is long overdue.

The Buddha explained the difference between those who think rightly and those who do not, in the discourses with Venerable Sariputta and Venerable Mugalan. These discourses throw light on the essence of right thought and there is much in them which would be relevant to the adjudication of disputes.

The duty of dispensing justice, which according to Buddhism, is one of the foremost duties of a ruler, is delegated to the judiciary by the sovereign. In dealing with the judicial duties of a king, the Tesakuna Jataka explains that a king should never succumb to anger. He should listen to both parties equally, hear the arguments of each and decide according to what is right in a decision free of favouritism, hatred, fear or foolishness (Jataka V. 109). All these duties devolve on judges, for they act on behalf of the head of state who has to maintain total integrity in the discharge of his functions, especially in his role as custodian of justice in his community.

Buddhist teaching attaches great importance to these fundamental duties of sovereigns. Since the duty of dispensing justice is carried out by the judiciary on behalf of the sovereign, all the duties attaching to the sovereign in this regard attach to the judicial office.

Since judges make law through their decisions, they help to shape the future. They should to bear in mind the words of the Dhammapada ‘with our thoughts we make the world’

2. Right concentration

Most analyses of the mental processes involved in judicial decision-making would end with an analysis of right thought.

Buddhism’s analyses of essential thought processes relevant to decision-making go further. They go on to develop the importance of right concentration as a prerequisite to right decision-making.

The factors impeding right concentration include physical and mental drawbacks ranging from hunger and anger to false impressions about parties. These are caused by wrongful processes of assessing people. Indeed, concentration of mind is a subject perhaps better developed in Buddhist literature than even in the books on psychology. There are discourses of the Buddha analysing concentration in depth such as Subha Sutta.

Right concentration involves rejection of irrelevant thoughts, seeing one’s decision in its overall context, avoidance of haste and considering a wide range of matters relevant in one way or another. There must be no distraction diverting the judge’s mind from this immediate purpose.

In the words of the Dhammapada 3.2, irrelevant thoughts distract the mind like a fish that is drawn from its watery abode and thrown upon land. The mind flutters to no purpose when it is so distracted. Unless irrelevant thoughts are summarily dismissed, they tend to flutter around like the fish just described, serving no purpose.

Concentration requires both a consideration of the wide range of factual matters relevant to the topic in hand and also a detailed study of the applicable law. No judge can be remiss in any of these. Right concentration helps to focus intensive attention on these matters.

Since the decision of a case involves intensive consideration of relevant facts and relevant legal provision, judges can never afford to be superficial in their consideration of these matters. While concentrating intensely on the minutiae of the written law, they must pay due attention to the overarching principles of law and equity relevant to the matter.

Right concentration requires a realisation that one is discharging a solemn trust. One is not only deciding a dispute between parties but also laying down a precedent which may operate for many years to come.

Another aspect is that the work one is engaged in must be looked upon as a privilege and not a burden. Buddhist teaching reminds us that taking joy in one’s work would make concentration easier. In the words of the Buddha ‘from gladness comes joy, with joy the body becomes tranquil, and the mind that is happy becomes concentrated’. (Dhammapada 1.74)

It is patently clear that right concentration on the part of the judge is an essential part of the judicial process.

3. Right Mindfulness

Right thought and right concentration by themselves do not suffice. Buddhist thought takes us further into the necessity for right mindfulness.

A case affects not only the two parties involved, but others around them and society as a whole. This wider perspective needs also to be taken into account by the judge.

One must be mindful of the effect of one’s decision upon those around the litigants. It must be perceived as a fair judgment. Sufficient reasons must be given for the judgment. Judges often deliver judgments without due consideration of the need to make the reasons for their decisions clearly understood by litigants and by society in general. This means that the judge must take great care in formulating the judgment so that the reasons for it become patently clear and acceptable to all.

There should also be mindfulness of the practicality of one’s decision, and mindfulness that one’s decision may have a progressive or a retarding influence on the development of the law. There should also be mindfulness of the need to temper law with justice and mindfulness of the shortcomings of the legal system which sometimes tend to pass unnoticed.

One is reminded of the famous address to the American Bar Association in 1906 of Roscoe Pound, perhaps America’s outstanding legal academic, on ‘Causes of Popular Dissatisfaction with the Administration of Justice’. Pound, then a young law professor, jolted the American legal profession out of its complacency by giving them a better understanding of the numerous flaws which tended to pass unnoticed because lawyers and judges did not subject their work to a mindfulness of its impact on society. The Noble Eight-Fold Path would avert much of this dissatisfaction.

Just as there are discourses dealing in depth with right concentration, there are discourses dealing in depth with right mindfulness. For example there is the Mahasatipaththana Sutta: The Greater Discourse on the Foundations of Mindfulness ( See The Long Discourses of the Buddha: A translation of the Digha Nikaya, Maurice Walshe, Wisdom Publication, Boston, 1987, pp 335-350) These show the depth of thought that Buddhism has devoted to such concepts.

4. Right vision.

Buddhist thought regarding correct decision-making also goes into the area of right vision. Correct decision-making requires a long term view of the consequences of the decision for the future.

In legal systems based on Common Law procedures, decisions of the higher judiciary themselves make law and Supreme Court judges need, therefore, to be intensively concerned with the long-term effects of their judgments. A long term vision is therefore essential to the proper discharge of their functions.

If Buddhism thus requires long term vision for the decisions an individual takes even more so would it require such a long term vision for judges.

Many a judgment is given without such a vision of the long term future. Environmental damage, violation of the rights of future generation and unawareness of interdisciplinary perspectives are often the cause of judgments which, though appearing to solve the immediate problem, produce long-term damaging effects.

Moreover, modern society is governed largely by political and economic considerations, both of which have short-term perspectives. All over the world, the ballot box, which is two or three years ahead, determines political decisions. The balance sheet, which is less than a year ahead, determines economic decisions. These are the time frames within which most modern decisions affecting the rights of the people are taken. It is the judicial process that can provide the corrective to these short-term perspectives, and this is provided by the requirement of right vision.

5. Right livelihood

This is an important part of the background to the judicial process.

Right livelihood as a judge means the strictest adherence to the rules of integrity. The mind of a judge must be free of favour, hatred, arrogance, fear and delusion. Total integrity demands that decisions must not be given for the judge’s self-improvement or to curry favour with those in authority or for financial advantage. These would be condemned outright by the Noble Eight-Fold Path, and no judge, conscious of the dignity of his or her calling, could entertain the idea of any departure however slight from the principles of right livelihood during his or her tenure of judicial office. Susceptibility to any form of influence violates the fundamentals of the Noble Eight-Fold Path and justly earns the condemnation of right thinking citizens.

As the Buddha himself observed when on one occasion some monks had told him that certain judges accepted bribes, ‘a person who is a guardian of the law is one who abides by the law’.

Since the judiciary is one of the most exalted vocations, the rules regarding right livelihood apply with special force to the judicial office. Failure to achieve this is a breach of this noble teaching. It is also a betrayal of trust, and a betrayal of the duty owed to one’s people, to one’s nation and, above all, to one’s conscience.

Each one of the ingredients of proper judicial conduct such as independence, impartiality, integrity, scholarship, competence and diligence has been elaborated on in detail in Buddhist scriptures written over the centuries and these can greatly illuminate our understanding of such conduct.

6. Right speech

A fundamental duty of the judge is right speech — whether in the wording of the judgment or in the handling of court business or in the way lawyers and witnesses are addressed. Right speech in the judgment and right speech on the bench are essentials of the judicial function.

The judge’s knowledge of language needs to be comprehensive. A serious flaw in current legal education is the lack of knowledge of linguistics, for linguistics shows us that almost every word is capable of a diversity of meanings. Indeed the very word meaning has at least twelve different meanings.

A flaw in legal and judicial reasoning coming down to us from the 19th century is that legal propositions should have the precision of a mathematical equation. Many lawyers still function under this belief induced by the legal positivism of the 19th century. This is a fallacy. Words such as justice, equity, right and duty attract such a vast variety of meanings that judges must equip themselves with basic linguistic knowledge to assist them in the art of interpretation. As Lord Mansfield, a famous English judge, once observed, most of the disputes in the world results from words.

It is interesting to note in this connection the comment by Professor K.N. Jayatilleke:

“The Buddha, again, was the earliest thinker in history to recognise the fact that language tends to distort in certain respects the nature of reality and to stress the importance of not being misled by linguistic forms and conventions. In this respect, he foreshadowed the modern linguistic or analytical philosophers”. (The Message of the Buddha, K.N. Jayatilleke, 1974, p 33)

The correct use of words and the correct manner of their interpretation are indispensable for a judge. This applies not only to the writing of the judgment, but also to the handling of witnesses, to the interpretation of documents and to interaction with lawyers.

It must be remembered also that right speech is required of a judge even outside the court. Judges command respect in society generally by reason of their office, and this respect must not be diminished by use of rude or indiscreet language even outside the court house.

7. Right action

Here is another important area for proper judicial conduct. The actions of a judge are under observation by the people and the litigants when the judge is on the bench. The judge’s behaviour must be dignified, and every aspect of conduct in court needs to protect the dignity of the judicial process.

It is the judge’s duty to ensure that unnecessary postponements are not granted, that unnecessary time is not taken off from working hours, that Court registers are properly maintained, that litigants have access to the records and documents to which they are entitled and that the accused and witnesses receive proper treatment and facilities. There are officials whose duty is to attend to some of these matters. Yet they function under the overall supervision and authority of the judge. The judge is not fulfiling the requirement of right action if he or she leaves such action to subordinates without the necessary element of supervision.

Right action means also the dedication of the right time and effort to the study of the case, the avoidance of haste and due compliance with the rules of judicial ethics.

Judicial ethics are a body of universally accepted principles regarding judicial conduct and they have been summarised in compilations such as the Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct which are widely accepted and followed in many countries. They cover a wide range of matters concerning impartiality, integrity, propriety of conduct, independence, equality, competence and diligence.

The judgment itself is the final action taken by the judge. It must be as correct in law and in every aspect of fact as the judge can possibly make it. It is indeed the ultimate crystallisation of judicial action. Right action also covers steps taken consequent on the ruling given by the judge.

8. Right effort.

The judicial process requires a vast input of effort in the study of the facts, the study of the law, the management of the court, the organisation of the judge’s time, acquaintance with latest legal developments, pursuit of the necessary academic knowledge and a vast number of other factors. It is the judge’s duty to be acquainted with the latest legal developments, both in the domestic and international legal systems. The judge needs to do this to the best of his or her ability, for being a judge is not merely a form of employment. It is a vocation akin to the priesthood, for it is dedicated to the pursuit of the highest ideals.

The remuneration received by a judge is probably far less than that received in other important walks of life. The effort called for requires a sense of dedication to this high calling and is not a quid pro quo for the salary received.

Conclusion

Judicial decision-making is one of the most solemn and responsible tasks entrusted to a citizen. Judges need every form of assistance and inspiration to guide them. The Noble Eight-Fold Path is an infinite repository of wisdom. It can help significantly in the proper discharge of the noble duties of the judicial office.

There is a beautiful stanza in the Diga Nikaya in which the Buddha himself made an observation relevant to those who discharge the judicial function. “If a person maintains justice without being influenced by favouritism, hatred, fear or ignorance, his lustre grows like the waxing moon”.