Sunday Times 2

The missing ‘link’ in the 19A Bill

The Supreme Court in its determination of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution has ratified a premier-presidential system for Sri Lanka. Before delving in to the SC judgment, one first needs to understand where Sri Lanka stands at present as a regime type under the 1978 Constitution.

Regime types are categorized based on government responsibility. One might ask: What is government responsibility? ‘Responsibility’ means the liability to be removed or dismissed. The meaning of ‘Government’ is sometimes given an extended definition to include the Cabinet, its ministers and departments. Some constitutions contain this extended definition (for example, the Portugal constitution — a widely discussed semi-presidential system — contains this extended meaning under Article 183 which provides that ‘Government comprises the Prime Minister, other ministers, state secretaries and under-secretaries.) The 1978 Sri Lankan Constitution, too, arguably contains this extended description of Government under Article 43, which provides that the Cabinet is charged with the ‘direction and control of the Government of the Republic’. In effect, the ‘Government’ in any regime type is that executive policy making body whose length of survival is definitive of which political actors wield the electoral mandate to be in power — that would be the Cabinet, or its equivalent, the council of ministers, or, by whatever name a constitution might call it.

Accordingly, in pure presidential regime types, the government (or Cabinet) is not responsible to the legislature, but to the President. In pure Parliamentary systems where there is no popularly-elected President, the Cabinet is responsible to parliament as the assembly could dismiss it with a motion of no confidence. There are also semi-presidential systems where a popularly elected President exists along with a prime minister and a Cabinet (that is the Government). Therefore, the Executive in semi-presidential systems comprises a popularly elected President and the Government. Government responsibility in semi-presidential systems varies. In semi-presidential systems that are presidential-parliamentary — like the Weimar Constitution and ours — the Government is responsible both to the elected President and Parliament. In that, the Cabinet under the 1978 Sri Lankan Constitution faces dual responsibility as it stands dissolved both by a parliamentary no-confidence motion, and when the President removes the Prime Minister. In semi-presidential systems that are premier-presidential, the Government is responsible to parliament.

The 19A bill has removed the dual responsibility of the Cabinet and moved towards a premier-presidential system where the Government is responsible only to parliament. Clause 11 of the bill provides for an Article 48(2) on Government responsibility to parliament.

The Supreme Court has embraced this shift towards premier-presidentialism. However, typically in premier-presidential systems there is a dual executive where the head of the State is the elected President and the head of the Government is the Prime Minister. The most popular example is the French model. Whether the clauses in the 19A bill referring to the PM as the head of the Government requires a referendum was a key question before SC. The Supreme Court has accepted that the President is not the unfettered sole repository of executive power, and that the executive power should not be personalised in the office of President.

“The case for a dual executive in Sri Lanka:

However, the court struck down the clauses referring to the PM as head of the Government and as Government formateur on four bases – (1) there must a ‘link’ between the President and the person exercising executive power, (2) an express delegated authority or permission given to the PM by the President is absent, (3) the President must be in a position to monitor those who derive authority from him, and (4) the President must retain the ultimate act or decision. It stands to reason then, the Bill would not require a referendum if this missing ‘link’ is installed with an express delegation of authority by the President, together with his control power to monitor.

One can identify several reasons to move towards a dual executive where the President is the Head of the State and the executive and the PM is the head of the Government. The first is that, the Supreme Court has given approval for the establishment of a premier-presidential system. It is evident that Sri Lanka cannot shift to a pure parliamentary model without a referendum, as it would result in the repeal of a popularly elected executive president. But the closest we can get to a parliamentary system is to be premier-presidential and construct a dual executive.

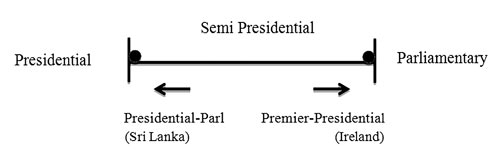

The following figure somewhat identifies Sri Lanka’s location as a regime type. We are currently a semi-presidential regime, which is presidential-parliamentary. The Sri Lankan constitution, given the excessive powers of the President, stands on the left margin of the scale of semi-presidentialism being closer to the pure presidential category. The more a constitution moves to the right on the scale of semi-presidentialism, the lesser power an elected President wields and the closer it gets to a parliamentary system. This heightens democratic performance. Ireland stands on the right margin of the scale of semi-presidentialism. However, Ireland is often regarded as an exception in the semi-presidential category as its constitution does not grant powers to the elected President and therefore parliamentary in practice. So, what needs to be done is to establish a dual executive that does not make Sri Lanka’s elected President a mere figurehead like the Irish President.

The reason why the framers introduced a popularly elected President in Sri Lanka was stability: to prevent constant elections when governments break during unstable coalitions. In the second reading of the 1978 Constitution R. Premadasa submits that in 1960 the Government did not last the throne speech and that two elections were held that year. So it is not required that the elected President dominates, and that the PM and Cabinet must be subordinate.

In fact, the framers intended that Parliament must ultimately control the executive President. R. Premadasa submits that it is for this reason that the President is finally checked by Parliament mainly through its control over finance, and the power to veto legislation was denied to the President. This is arguably the reason why the structure of Article 4 provides for a Parliament in the first instance under 4(a). The executive President comes second under Article 4(b). The structure of Article 4 was undoubtedly influenced by the US constitution. The founding fathers of the American constitution intended Congress to be more important. Madison in Federalist #51 states that “in republican government legislative authority necessarily predominates”. Accordingly the US Constitution gives prominence to Congress in Article I. When the President is the head of the Government and the government formateur under the Sri Lankan Constitution he has indirect influence over finance by installing a ‘presidential Cabinet’ (especially so when he has a legislative majority). Therefore the exercise of executive power under Article 4(b) at present stands inimical to Parliament’s ultimate control of power under Article 4(a).

“The missing ‘link’:

One effective method to overcome this is to introduce a dual executive where the PM is the head of the Government who can operate as a check on the President. As Madison notes “ambition must be made to counteract ambition”. Neo-Madisonian theorists take this further and encourage organising government in terms of transactional relationships. In executive institutional design a transactional relationship between the PM and President would mean that once appointed the PM is not subordinated to the President and is given constitutional authority to prevent legislative encroachment by the President.

The Supreme Court has already laid down the method of designing a dual executive. First there must be a ‘link’ between the PM, cabinet and the President. Accordingly, one needs to insert provisions, which provide that there shall be a Cabinet of ministers entrusted with the authority of the President to determine and conduct the policy of the Republic. A provision that provides for an ‘expression of delegation’ by the President is required, so that, the Cabinet shall be formed and headed by the Prime Minister, summoned by the President to do so. Such entrusting of authority is quite common in premier-presidential constitutions like that of Iceland. The final act or decision also must belong to the President. For this reason some premier-presidential constitutions require the PM to keep the President informed of the external and internal policy of the country and to get the President’s signature for all Government decisions. However, the refusal of the signature is limited on grounds of illegality.

The President also can in his exercise of legislative power monitor Government through his power to invoke the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction with respect to Bills (such power has been effectively used by Portugal Presidents.) Moreover, the President can be given the power to convene the Cabinet through a notwithstanding clause which bestows overriding power. So it can be provided that notwithstanding the fact the PM heads the Cabinet, the President as head of the executive may convene the Cabinet to make directions for the due discharge of his powers under the Constitution and the law, and to determine policy relating to defence. However, to prevent a President from inventing situations of intrusion one can require that his directives must bear the countersignature of the Cabinet. Such checking mechanisms are prevalent in premier-presidential regimes. For example, to prevent rampant exercise of decree power (i.e. emergency regulations), the power to declare war, defence, the power to ensure conditions for free and fair elections Presidential directives must be made to bear the countersignature of the Cabinet as these powers affect People’s rights and franchise guaranteed under Articles 4(d) & 4(e). There can also be a provision to make the President liable to be questioned by Parliament through the Cabinet as the cabinet serves as the Bagehotian ‘buckle’ that links executive and parliament.

(The writer LL.M. (Harvard) is a

lawyer trained in Comparative Constitutional Law)