My days with the drummers

Whenever he is in Sri Lanka and that is at least once a year to meet up with doctors to discuss topics of a different realm such as bioethics, he makes time during his busy schedule to journey to the deep south.

This is to touch base with those among whom he spent more than a year as a youth. They are the ‘ritual specialists’ of this country who opened their hearts, their humble homes and their traditions to him from October 1978 to April 1980.

These days, though, it is with a heavy heart that 57-year-old social anthropologist Prof. Bob Simpson journeys to the area around what used to be “the small market town” of Akuressa.

Then with a group of drummers

“Most of my friends are dead and their children have left their rich traditions behind to take to what they believe is ‘more respectable’employment,” says Prof. Simpson who is Professor of Anthropology, at Durham University. Currently a Visiting Professor at the Colombo Medical Faculty, he is in Sri Lanka frequently to discuss bioethics, biomedicine and biotechnology.

Back in the late 1970s, it was by accident that he “picked” the drumming community of this country for his doctoral thesis, after his fascination with Asian culture drew him to India and Sri Lanka.

As we discuss his views on the customs and traditions of this community, an integral part of Sinhala society, Prof. Simpson goes back to the time when he accompanied them in the performance of their ritual drumming duties as well as other activities such as temple art work, astrology and elaborate healing rituals to bring relief to those struck by misfortune.

Born in Manchester, it was from Durham University that he secured his degree. For his doctoral studies (thesis produced in 1984) he chose this project in Sri Lanka. His thesis acknowledges a deep gratitude to his drumming “friends” who gave him “generous access to their lives and work, and shared, albeit briefly something of their sorrow and joy”.

Being drawn to the study of different cultures and ways of life as a youth, South Asia had beckoned. “My interest was initially in things Asian because of the different values,” says Prof. Simpson. His undergraduate studies were on Indian civilization and he also “read a lot” about Sri Lanka, immersing himself in the writings of historian and philosopher Ananda Coomaraswamy and anthropologist Gananath Obeyesekere.

In 1978, he spent time at Peradeniya, learning Sinhala under Prof. D.D. de Saram.

With a keen interest in understanding how a craft and ritual tradition was reproduced, he found that nothing or very little had been written about the different communities engaging in particular types of work in Sri Lanka, unlike in India. Originally, planning to do research on the Navandana (blacksmith) community or pittala (brass) workers, when he found another working in this field, he changed tack.

In the wake of a “chance encounter” with Prof. Bruce Kapferer of Australia’s Adelaide University, came an introduction to drummer, Cyril, the head of his family and through him to his kinsmen living around Akuressa.

His early days were spent travelling about the countryside, often with Cyril, in search of Cyril’s relatives. “It was an intensely frustrating exercise,” he recalls in his thesis. “The community was seemingly shapeless and scattered over a wide geographical area. Relatively, the area was in fact quite small, possibly little more than a hundred square miles of the Nilvala valley. However, the unreliability of public transport, the inaccessibility of many dwellings, the elusiveness of many key male informants and their nocturnal work patterns rendered days and sometimes weeks wasted in fruitless journeys.”

“Often as not, an uncomfortable three-hour trek in search of some important individual would be rewarded by the knowledge that the man I sought had gone away and would not return until the following day. My bemused hosts would offer hospitality of the best they could muster which I would consume alone, listening to animated whispers from behind thin walls,” he states.

A white youth from an affluent country mixing with a village community was considered “quite odd”, recalls Prof. Simpson of those days, but he persevered, starting off in one community, working out their genealogy and then gradually getting to know different groups.

He found a paradox – the community played a centre-stage role in society with their healing rituals but at the same time there was much discrimination against them in the late 1970s.

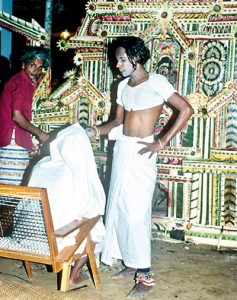

As he was gradually welcomed into their homes, he accompanied them on their travels to distant villages to perform their all-night rituals or thovil. His interest was particularly sparked by Bali Thovil, “an astrological ritual intended to combat the malign influences of the planets”. Bleary-eyed he may have been but he got an insight into the complexity of their work. Long would be the nights breaking rest, munching kavum and kokis and gulping down steaming cups of plain tea.

While studying kinship, marriage and the way in which different skills and knowledge were passed on between key figures in the community, he also attended 36 major healing rituals and a number of smaller ones which he observed, photographed and tape-recorded the songs, incantations and drumming.

During his early efforts to map the community, “information came slowly — a scrap of genealogical material here, a fragment of information about magical practices there and occasional attendance at all-night ceremonies”, he says. Even though he intended to live in a drumming community, one of his “greatest” disappointments was that he was not able to do so. Although he was in close contact with several communities and frequently stayed three or four nights, he was just a visitor, with pressure on living space in the community making longer visits just not possible.

Prof. Simpson now

He also feels that though he was always welcome as a visitor, in such a “secretive and turbulent” community, it would have been far too threatening to have him there all the time, questioning their “general knowledge” and causing potential imbalances in a finely-calibrated system.

“The commodity in which I was interested was crucial politically to the internal working of the community and consequently its revelation or concealment from me was not just accidental,” he says.

Referring to all healing rituals performed by the community, Prof. Simpson says that a process of framing is carried out whereby the individual and his or her affliction are progressively located within the cosmos. Obeisance is paid to all superior and higher beings in the cosmos, before moving to more specific and subordinate realms.

Ideas surrounding misfortune and malevolence or ‘dos’ can be found running through all the various activities carried out by the community. Dos is an inevitable consequence of the passage of time and it is the negative consequences that the drumming community has to deal with in various forms. Their role is to remove it, absorb it, deflect it and anticipate it on behalf of their clients.

In the drumming community’s ritual occupation, they were ‘located’ within the magical, animist or apotropaic domain of belief and action. They had the wherewithal to identify and combat the malign effects of demons and spirits, of man and deity. Their services were called upon when the problems of this world bring suffering to mortal bodies and abstract doctrines can offer but little in the way of consolation or relief.

“These ‘ritual artists and craftsmen’ who operate within a complex, literate and highly stratified society in the south with its distinct and vibrant cultural identity are a clever people,” says Prof. Simpson who closely studied the social mechanisms which enabled them to pass on their specialist knowledge and skills within the community and orchestrate these skills as a service to wider society.

“The process of rendering specific actions and utterances as meaningful, I take to be fundamentally linked to the nature of ritual performance: It is through the performance of carefully orchestrated actions, the manipulation of symbols and the enactment of metaphors within a wider context, which the ritual patron/patient plays a crucial role in defining, that intimations of a transcendental order are communicated and experienced. Within each ritual, a cosmology is fashioned at the local level and the participants located therein,” he states in his 500-page thesis.

As he went about with them, he became more and more puzzled about the treatment meted out to them by society. “These people who were a pivot in Sinhala culture were treated badly.”

His interactions with this colourful but socially-discriminated group threw up some disturbing information. Until recently, the men had not been allowed to cover their upper body while the women could not wear blouses, only use a wrap to cover their breasts. In many upper-caste houses, they would have to sit in a bage-putuwa (half-chair or low chair) while they would be addressed in derogatory language interspersed with “umba”.

The men, women and children accepted their plight but valued the fact that they were respected for the services they performed, says Prof. Simpson, pointing out that in the wider context, the community which included exorcists was also feared a little bit.

“They not only had the power to heal but were also adept at performing kodivina and huniyam or reciting vas-kavi to harm people. People were very superstitious about them,” he explains.

Thovil troupes could vary in size and be made up of dancers, drummers and mantrakarayas with their widerange of skills being synthesised into incredible performances.

“The performers would be closely related, with kinship valued immensely. Marriages between cousins or nena-massina (mother’s brother’s daughter or father’s sister’s son) were common to keep the tradition within the family. Marriages were not just within a caste but more so within the family,” he says, adding that endogamy was followed quite strictly.

He would come across a drummer whose brother-in-law was a mantra-karaya or gok-kola whizz while the women who did not perform, apocryphal though it was, knew all the kavi and the secret sequences. Prof. Simpson creates the vibrant image of this “fabric of tradition” with men being the weave and women the warp.

Prof. Simpson’s return to the community in 1995 was heart-wrenching, for the changes were obvious. Many of the Gurunnanses he knew had died and their heirs who were young parents just did not want their children to follow in their footsteps, as drumming was considered a stigma.

To his regret, Prof. Simpson realized that younger members of the community had found employment in tourist hotels, taking up mask dancing and drumming with only older men continuing the rituals. They were catering to small groups of people inside homes rather than the 400-member gatherings in public places of earlier days.

While his shift in interest to bio-ethics makes Prof. Simpson return to Sri Lanka, there is a tinge of sadness as he sees the drumming community giving up something very powerful – an indigenous form of psychodrama to address the suffering of minds and bodies.

“It’s a living thing, an organic thing. What has happened now is that there is greater interest of it as a heritage and not a living tradition,” laments Prof. Simpson, for this dying art, asking whether it is the swansong of the drumming community.

| Rituals for mental and physical healing Here are some of the rituals, meant for both physical and mental healing that Prof. Simpson was privy to, described in his own words: He is most potent at mid-day and mid-night, capturing his victims in his gaze (baelima) and infusing them with his demonic essence (dishti). The effects of Maha Sohona, once identified, are relieved by the exorcist (edura) by actions aimed at several different levels. These levels fall into two categories — the elaborate observance of the etiquette of making offerings to Maha Sohona and his demon associates and purification and reassurance of the patient using a variety of ritual devices which include comedy and drama. The first phase of the ritual is between 6 p.m. and 10 p.m. when offerings (dola) of burnt and fried seeds and foods, shredded flowers, alcohol and other impure items, all deemed highly attractive to demons, are made on specially constructed trays (pideniya and tattuva). It is brought to an end with an episode known as ‘Death Time’ or ‘ava mangala’ in which an exorcist presents himself as a corpse in order that the demons might avert their interest from the patient onto his apparently dead body. This episode is particularly dangerous for the exorcist as he lies in a corpse-like position before the patient, people wailing over him, as if in mourning. Eventually, he is carried away on a mock funeral bier (daraheva), to a similarly mock cremation ground (kurälaya), where in his stead a straw image (pambaya) is cremated. The demons are deceived into accepting an inanimate sacrifice by the manipulation of the symbols and signs of death and cremation. The second phase over the mid-night period contains wild, exhausting dancing and hypnotic drumming heightened by the inhalation of incense, in the midst of which the dancers take upon themselves the essence of the demon. It is communicated to the audience in such feats as juggling, fire-eating and gravity-defying acrobatics. Between 1 a.m. and 3 a.m., marks the end of the ‘serious’ business of the ritual and there is a shift from a presentational mode to a discursive mode of ritual performance. Offerings are made to the god Mangara, the deity believed to assert authority over Maha Sohona. The final major episode of the ritual is the Dahata Paliya, the Parade of the 18 Sanni Demons, the bringers of disease. Many of the demons come as comic characters, developed in the hands of the exorcists. Demons which were once terrifying are rendered harmless and pathetic. The ritual is brought to an end shortly after sunrise. Suniyam is not an exorcism (yak thovil), but a blessing ceremony (santiya). The demon to whom the ritual is directed, Suniyam, occupies a slightly elevated position in the pantheon as he spends half his time as a demon (Suniyam Yakka) and the other half as a god (Suniyam Devatäva). Therefore, the ritual approaches made to him are somewhat more refined. When sorcery (kodivina) is performed, it is this demon which is invoked and it is to him that an appeal is made when a sorcery is to be cut (kodivina kepima). The first part of the ritual is taken up with carefully ordered rounds of invocation and supplication and offerings to the various demons and their associates. The second part is taken up with the enactment of a mythical drama and an attempt to stop the physical effects of sorcery by cutting various objects. |