Sunday Times 2

Gamble saved couple as tsunami roared onto them

The deafening sound of a giant wave crashing on Peraliya beach is what 33-year-old Nirmala Fernando heard this week when the country fell silent for two minutes to remember the tens of thousands who were killed in the tsunami 10 years ago.

“I still hear the ‘hoo’ sound of the water charging our way. Even today, I see the giant wave in my dreams,” says Nirmala who was travelling on train No: 50 on December 26, 2004 to visit her parents.

For many days afterward, if she managed to sleep at all, she would see those waves in nightmares as it swept up the train she was travelling in and hurled it inland, leaving it a twisted mass of wreckage.

The memorial train on its way to Peraliya. Pix by Indika Handuwala

On Friday, the original Train No. 50 locomotive and five of its carriages, restored in 2008, set off from Colombo at the exact time the ill-fated train set off a decade ago. On board were Nirmala and other survivors and the relatives of victims.

The tragedy killed almost 1,000 passengers on board the Samudradevi and about 40,000 islandwide. Ten years on, the memories of the devastation and loss of life are still fresh.

“It was the first time we were visiting Ammi and the family since getting married. I was

Nirmala: A survivor of the tsunami train tragedy alighting at Peraliya

taking gifts: I had bought clothes for Ammi, and Nangi’s entire book-list for the new school year. I had put nice covers on the books,” said Nirmala, remembering how eagerly she had prepared for the visit to her family.

Early that morning, she and her husband, Asela, manager of the Moratuwa branch of the Sporting Star bookie agency, caught the train from Colombo.

The first tsunami wave came at them as the train stopped at an unexpected red signal outside Peraliya.

A small, sleepy village hidden in the shadow of the tourist hotspot, Hikkaduwa, Peraliya was unknown to most before the train tragedy of 2004. Many of its inhabitants made their living from fishing and cottage industries such as coir rope weaving. A decade later, the village is known the world over, and many tourists stop at the Tsunami Memorial to pay their respects when they pass the town.

“The engine and the first two carriages were washed away in the first wave. We were in the next carriage,” said Nirmala.

Many in her carriage were campus students, close to her own age.

Sounding the bugle

“They were going home for the holidays. There were children there too,” said Nirmala, now herself a mother of two.

“My husband and some others got down from the train to check the situation but the water gushing toward us rose up to their necks. Many in the carriages started praying, many were frightened,” Nirmala said.

Even in that trying hour Nirmala didn’t hesitate to help another fellow being: a villager who came running to the train after the first wave hit was stark naked; the waves had torn away his clothes. Seeing his plight, Nirmala gave him a skirt she had bought as a gift for her mother so that he could cover himself.

Tears in her eyes, she recalls how she watched the man drown a short time later when the second wave hit.

Sujatha offering Atapirikara in memory of her youngest son

Her voice breaks as she recalls those moments.

Surviving villagers from Peraliya were clinging onto the carriages on the side away from the sea, hoping to use the train as a breakwater shelter against the oncoming wave. They were wrong.

Asela Fernando’s quick intelligence saved him and his wife.

Following his instructions, Nirmala clambered out of the train on the side of danger, the open sea, and hung onto the rails of the footboard.

“The carriages that had been swept away in the first wave had fallen over on the side away from the wave, not being able to stand the pressure of the water, so my husband told me to hold on to the footboard of the side the wave was coming from. He was right behind me, hugging me,” said Nirmala.

“My husband said, ‘The wave is coming! It’s uprooting trees! It’s coming, but don’t be afraid, hold on tight.’

Japanese monks at prayer

“When the second wave came, it pushed the carriage over and we were on to the windows. Everyone inside the carriage drowned.”

Those who had huddled against the land-side of the train were crushed as the 9 metre high wave pushed the carriages over and swept the train inland.

Nirmala’s voice breaks as she recalls how her carriage hit a tree and the impact threw her out of Asela’s arms into the water. Fortunately, she still managed to grab onto part of the carriage.

“My husband thought I had drowned but someone rescued me and took me to the nearby temple. To this date I don’t know who helped me. I don’t remember what happened,” said Nirmala, grateful to the stranger who saved her life.

“If not for my husband’s quick thinking I won’t be alive today.”

Asela Fernando said his only concern was for Nirmala, who could not swim. He became wedged in a roof and suffered hip injuries. He was brought to the temple by villagers and found his wife there. Nirmala says that she woke to consciousness with her head in Asela’s lap.

Thankful for their luck, Nirmala Fernando clasped her prayerbook tight at the Tsunami Memorial at Peraliya on Friday for the annual memorial service organised by community and non-governmental organisations.

At the same ceremony, holding a “mataka wasthra” cloth in the ceremony of remembrance of the dead, 60-year-old M.W. Sujatha sat as a Buddhist priest chanted gatha verse.

Foreigners among the mourners

Her eyes shone with tears as she spoke of her youngest son who was killed in the tsunami’s second wave.

Sujatha’s house, right opposite the site where the memorial now stands, had been one of the first to be hit by the massive waves. She ran to safety with the rest of the family.

Her youngest son, who had been away, had come looking for them after the first wave, surviving neighbours later told her.

“He had been worried about us. I was told that after helping many people who had been caught in the first wave he had been running to safety when he got caught in the second wave.

“For more than three months I refused to believe my son was dead. He was such a strong man!” said Sujatha.

Living close by, she comes to the monument several times a week to clean the area and pay tribute to her son. She runs a small shop near the Tsunami Memorial and maintains the family on its proceeds.

Her only comfort is the dead youth’s son, who was barely two months old when the tsunami struck.

“I look after my grandson and daughter-in-law now. I can’t be sad. I am a Buddhist: I have to accept this. My grief is made bearable because there are so many who share the same grief,” she said.

“But when a child dies it’s a difficult thing to accept.”

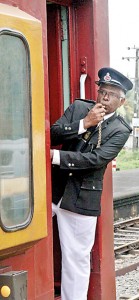

| Passing Peraliya: A railway guard’s regular encounter Braving haunting memories, Wanigaratne Karunatilake, 58, on Friday took the same journey he took ten years ago as the guard of the Matara-bound express train.  In the line of duty: Wanigaratne Karunatilake He was on a constant watch for signal changes as the Tsunami memorial train moved along the coastal line, on Friday carrying on board, the survivors and families of the victims of the tsunami catastrophe on December 26, 2004. “It was all chaotic that day, both our engine driver and assistant died. Only my second guard and I of the crew survived. Together we managed to save the lives of some of the passengers and others caught in the deadly wave,” Mr. Karunatilake recalled. He and some survivors managed to find sanctuary in a nearby temple on high ground, but they returned to the ill-fated train to look for any survivors when the surging waters subsided. With the assistance of the residents of the area, they rescued passengers trapped in the train. With a sense of duty, Mr. Karunatilake later lodged a complaint at the police station regarding the ‘train accident’. His family living in the coastal town of Weligama had also managed to escape the waves by getting on to the roof of their house. It was around 2 am next morning when Mr. Karunatilake reached home. “When I went home, I found that my friends were getting ready for my funeral, thinking that I was dead,” he said. A year later he managed to rebuild his house and move in. With 30 years of experience behind him, he says he is a seasoned train guard. He often works on the southern coastal line, and thinks about the tragedy when he passes Peraliya. But he does not panic. “In the past ten years, only once did the train stop at the same location as it did on the tsunami day, as we didn’t have the signal to proceed. That day I was a bit scared and unsettled,” he said. |