News

Erratic weather, market forces send veggie prices up

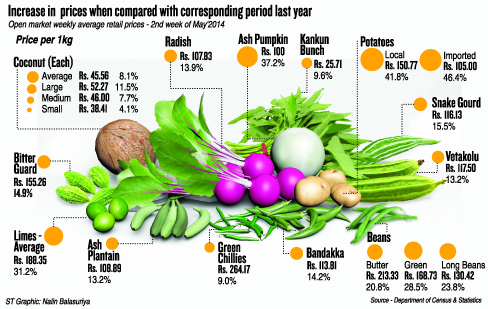

A scarcity of vegetables in the marketplace is pushing prices up steeply while continued drought in catchment areas has forced rice farmers to cut their cultivation by nearly half.

Fewer vegetables at DEC: Recent heavy rains washed away seedlings or caused them to rot

Vegetable prices increased so sharply that the Government this week made provision for consumers in Colombo and the suburbs to buy cheaper produce through Lak Sathosa sales centres. Officials were instructed to procure vegetables from farmers in Dambulla, Nuwara Eliya and Jaffna to sell at lower prices than available in the retail market.

But at the Dambulla Economic Centre (DEC), one of the country’s main vegetable wholesale hubs, produce was coming in slower than usual. Traders and farmers from the area said an abnormally intense spell of rainfall in April-May had destroyed new nursery beds and contributed towards the shortage. The heavy downpour had lasted around three weeks.

“The reason vegetables are so expensive is that the quantities are less,” said W.G.S.K Ratnayake, the 33-year-old chairman of the Samagi Govi Society, Atubendiyawa. “We cultivated the beds and put up the nurseries in April but the rains washed the seedlings away or caused them to rot.”

H.G. Kusumawathie, walks anxiously towards a stall where she had left some sacks of limes to be sold

Those who have produce are now selling it for higher prices, said Seneratne Bandara, a 52-year-old farmer from Kitulhitiyawa, Kekirawa. He had come to the DEC with sacks of yams. “But recently, when there was a glut, we sold a kilo of tomatoes for as little as two or three rupees and cabbage at around five rupees a kilo,” he said, despondently. “Whatever happens, we are sandwiched in between and it is becoming harder and harder to continue farming.”

Clutching a small purse in one hand, 58-year-old H.G. Kusumawathie, walked anxiously towards a stall where she had left some sacks of limes to be sold. She needed the money for medicine. “There is no water so there is next to nothing in my plots,” she said. “I plucked ten kilos of limes and bought 14 more kilos. I’ve left them with the mudalali.”

H.M.I. Somasiri : Didn’t sow his paddy fields to full capacity due to the drought. Pix by Mangala Weerasekera

Mrs. Kusumawathie lives alone in Batuhena near Bakamuna with her eight-year-old granddaughter. The girl’s mother is divorced and works in Kuwait. She didn’t know how much the limes would fetch her but said she had recently sold another batch for Rs. 60 a kilo.

It has been alleged in the past that a ‘traders’ mafia’ in Dambulla controlled prices. But a cross-section of people interviewed by the Sunday Times said that a combination of natural phenomena, market forces and circumstances were more likely to be the reasons for the current trend.

“Some areas of the country did receive heavy rains leading to a problem with nurseries in April,” said Agriculture Department Director General Dr. Wijekoon. “In Dambulla, where big onions are a success story, even those nurseries had a problem. But it was not the case everywhere.”

Dr. Wijekoon said another reason for the ongoing shortage was that severe drought had frightened some farmers into planting less. This was particularly true of rice. Around 400,000 hectares of paddy land is usually sown during the Yala season starting in April but the figure is down to 250,000 this year, he said.

W.G.S.K Ratnayake

“This prolonged drought is a problem,” Dr. Wijekoon affirmed. “We are not getting the normal monsoon we have every year, so there is an issue with paddy. We cannot go for full capacity.”

This was also true of other crops, said Mr. Ratnayake. “People were too scared to cultivate for the mid-season between Yala and Maha because there was no water,” he explained. “Water is released throughout the Mahaweli areas only once in ten days now.”

Sipping plain tea under a tree in Kaluwagahaela, Kandalama, 64-year-old H.M.I. Somasiri admitted that he was one of those farmers who hadn’t sown his paddy fields to full capacity. “I have four acres that I didn’t plant this season because with this drought I couldn’t take the risk,” he said.

But Mr. Somasiri did cultivate his other plot of paddy which was located closer to the Kandalama irrigation tank. “There is a leak in one of the sluice gates so some people are able to pump some water from the outlet,” he said. “That’s how I have been watering my fields there.”

“We were told that they will release water in the Mahaweli scheme on June 1,” said L.B. Kadukara from Unapanduruyaya, as he sat under a tree with Mr. Somasiri. They had just helped harvest yams from an adjoining field and said they would replant the cut stems when the water comes.

Nearby was a large irrigation well which had fed the yam cultivation. Farmers who could avail themselves of groundwater were less affected by drought conditions than others who depended on tanks for water.

Agriculture Department officials had earlier feared that there would be a ripple effect arising from the reluctance of farmers to take a risk with paddy cultivation. They thought it would turn them towards other field crops, thereby depleting seed supplies. A notice published on the ministry’s website warns: “The drought condition prevails [sic] in this period will lead to cultivate [sic] other field crops instead of paddy in Yala 2014. At this time the Department of Agriculture advised [sic] to use farmers’ own seeds in order to avoid the possible seeds shortage.”

But Dr. Wijekoon said this was no longer relevant as the Department has now secured sufficient seed stocks. “To give you an example, we now have 77,000 kilos of groundnut seeds for distribution,” he said. “That is enough for the whole country.”

Another reason for the dearth of vegetables was that farmers were in-between seasons, Dr. Wijekoon continued. “One season normally starts in April while the other begins in October,” he explained. “Now, in most places, the crop is at a young stage. This problem will be resolved in two to three weeks when the crops mature.”

The Director General insisted that there would be no rice shortage because an exceptionally good Maha season that ended in January had yielded sufficient stocks. This meant the country had enough rice till December 2014, he said.