A glorious vision all but forgotten

“Ah, chaste permitted wilderness below our house

complete with winding walks and warbling stream

designed to breed debate and poetry

Jennings’ vision for Peradeniya: “No university in the world would have such a setting”. Pix by Ashwin Dominique Jayalath

nursery of our love … You will remain,

symbol, monument, and not you alone

but all this involuted dream,

apt replacement for the finest bit of tea land

in the Midcountry. Symbol, monument,

not, please, of us … but of

Those sage dreamers, our progenitors …”

(from “Elegy for Peradeniya” by Ashley Halpe)

We have forgotten Sir William Ivor Jennings IV.

“No,” you may say, “he was the man who helped draft our constitution.”

Yes, that too, but his life’s work was what is now the University of Peradeniya. He had a most glorious vision for the university, which he worked tirelessly to achieve in the little time he had. And on a day like today, April 20, 1954, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh ceremonially declared the University of Ceylon “more open than usual”.

Sixty years hence, the date, the name and the vision seem all nearly buried, and one wonders if the “sage dreamers” dream has died.

The creation of a university

Jennings was lecturing at the London School of Economics when World War II broke out in Asia. During the long vacation of 1940, he found himself “entirely at a loose end” despite “doing some writing” for the Ministry of Information and being involved with the BBC as well as researching for and writing his own books. But “It did not seem enough,” he wrote. So when the post of Principal at the Ceylon University College was advertised, Jennings took the project on wholeheartedly.

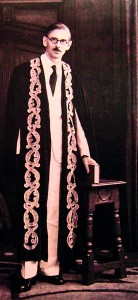

Sir William Ivor Jennings: The scholarship boy who understood what education could do to a human being

But getting to Ceylon proved more complicated than expected. Jennings’ family had to follow him on a later ship, the “Staffordshire”, which was bombed at sea and beached in Scotland, one of his children having a serious injury. The incident had a hardening effect on his mind, and one might even say it set the stage for the great work which would follow. It gave Jennings a psychological independence not only from Ceylon, which he had undertaken to serve, but also from the British colonial authorities who had let him down. And he became a force to reckon with:

“I was in Ceylon to do a job and I would do it; if I found that owing to ignorance or procrastination or ineptitude or corruption it could not be done, I would go home. I told nobody of my resolve, for it was unwise to threaten; but I took risks which I would not normally have taken, because the consequence of defeat seemed admirable – I should send in my resignation and go home to look after my homeless family and injured child and to do something more useful.” (The Road to Peradeniya)

Prof K.M. De Silva

When he finally arrived, he found that Ceylon University College had “nothing like a university atmosphere,” Jennings wrote. The students, he thought, were badly mannered, and there was a complete lack of corporate spirit. “Both students and staff regarded the College not as an entity with a life and tradition of its own, but as a Government department doling out courses for London examinations.”

The College had been established in response to the recommendations of the Macleod Committee, made in 1912. The reparation of what the committee saw as a “fragmented” tertiary education system was only partially complete when Jennings arrived in March, 1941, as their proposal included the conversion of this university college into a fully fledged university at a later date. Thus the creation of a university was part of Jennings’ commission as Principal of Ceylon University College, and this task, he took to heart.

A constitution for the university had been drafted in 1930 and soon after his arrival in Ceylon Jennings began the process of amending the documents for presentation to the related Executive Committees. He had done his homework before he arrived, and the obvious first step seemed to be to secure university autonomy. Working closely with Dr. C. W. W. Kannangara, the Minister for Education, Jennings had the new Bill approved by April 1942.

Prof. K. M. De Silva, acclaimed historian, is awed by Jennings’ passion and attention to detail.

“How many people can do what he did?” he asks. “He would have had a few weeks – and in this heat! … It was the way he worked … He worked very hard, and you couldn’t bluff him. He wrote a beautiful draft.”

The proposition to take the university out of the control of a small group of seven politician members and into the hands of a larger independent body consisting of a Senate and University Council was accepted and passed by the State Council. As far as Jennings’ autobiography reads, it was dramatic work:

“On the 31st of March, while the Bill was being debated, an air-raid warning was given … I took shelter with the [State] Council and hoped that the interruption would not be long, for I wanted that Bill through.”

“The fact that a colonial functionary could feel such excitement about something he was doing in a colony, knowing that independence was imminent is something I find remarkable,” says Dr. Deepika Udagama, Head of the Department of Law at the University of Peradeniya.

“The fact that a colonial functionary could feel such excitement about something he was doing in a colony, knowing that independence was imminent is something I find remarkable,” says Dr. Deepika Udagama, Head of the Department of Law at the University of Peradeniya.

Dr. Udagama makes no distinction between Jennings as an “outsider” and Sri Lanka’s “national” heroes”. As a student of law and as a beneficiary of Jennings’ legacy at Peradeniya, Dr. Udagama is convinced that “Jennings has done for Sri Lanka more than what most political or any other local personalities have done”.

Professor William Ivor Jennings was appointed Vice Chancellor of the University of Ceylon on June 4, 1942:

“The Proclamation was issued on the 12th of June, and I personally ran up the temporary University flag – the golden lion bearing what the irreverent called an ice-cream cone – on the 1st of July. I thought it typical that I should have to do the job myself. I ordered a clerk to have the flag put up and he, of course, ordered the caretaker to do it. Being a little sentimental, I was watching from down below, saw that the flag was sagging at one end, climbed the tower and adjusted it with a safety pin. We are evidently a unique university, not only because we were born during an air-raid, but also because the first vice-chancellor nailed the first flag to the mast with his own safety pin.” (The Road to Peradeniya)

This was Jennings’ original commission, the creation of a university for Ceylon. He carried the work out with the same determination he began with, and his autobiography, “The Road to Peradeniya” reveals how passionately he was invested in the process. Ironically though, he is better known for his unofficial yet instrumental role in the acquisition of Ceylon’s independence from colonial authority. His legal expertise being well recognised and acknowledged soon after his arrival, Jennings was often casually consulted by local leaders on matters of national governance.

To achieve what Ceylon achieved for herself in terms of independence, with the dexterity with which it was achieved, “you must have a man like Ivor Jennings who can write complicated things in simple language,” says Prof. De Silva. “And then you need a man going to be Prime Minister who can read it, understand it and then explain it in even simpler ways to other people.”

It was Jennings’ belief that as an academic, he held knowledge in trust for the public, and that if his assistance was wanted, it was his privilege as well as duty to give it. So on May 26, 1943, when the “Declaration of 1943” arrived, the triumvirate was born, D. S. Senanayake, Oliver Goonetilleka and Ivor Jennings, acting together for nearly five years, until in July, 1947, the British Government agreed to Dominion status for Ceylon.

Scholarship boy

William Ivor Jennings IV was born the son of a carpenter. He was encouraged to read, and had a little black box in his room, on which he would climb to make his orations as parson, lawyer or politician. Never once was he a university lecturer because he had not yet even heard of a university. In his family, landing a clerical job in the city was the height of ambition.

But William Ivor Jennings IV was the beneficiary of an educational system that valued humanity above all else, and allowed him to dream big. He did not know it then, but Jennings’ story started picking up when the Headmaster Mr. Kempster made an exception and allowed him to join Redfield Council School, despite living outside its catchment area. From there, at 10 years old, Jennings won a scholarship to “the city school”, Queen Elizabeth’s Hospital (QEH) in Bristol. From QEH he won more scholarships to Bristol Grammar School. Here he played rugby in the first XV, became a House Prefect, School Prefect, House Captain and then the Head of the School. When in 1922 he won the first scholarship to Cambridge from Bristol Grammar in seven years, he “exercised his privilege” of walking up to the Headmaster to ask for a school holiday.

“It was sweet,” he later wrote of the memory, “but not so sweet as dropping over the line in the last house match, with the ball under my tummy.”

What mattered to Jennings was not that Bristol Grammar had led him to Cambridge, and Cambridge to global influence, but that in both these places he had learned to be part of a community of likeminded people. “It created in us a sense of responsibility, not only for the others, but for ourselves. We knew that the school depended on us and we carried that idea, I think, into our universities and then into our life as citizens.”

William Ivor Jennings IV died at 62, not a parson nor politician and only somewhat a lawyer. He had birthed the University of Ceylon, served as Vice Chancellor of the Universities of Ceylon and of Cambridge, taught around the globe, wrote scores of books and been an integral part of the political histories of many nations.

Jennings far exceeded the highest ambitions of his family, and his autobiography is dotted across the chapters chronicling his childhood and “eddication” with the names and graces of those benefactors who made it possible. The University of Peradeniya was the scholarship boy’s way of giving back to his beneficiaries what his benefactors had left for him.

For a thousand years to come

“The point of his story,” Dr. Udagama says, “is that such a person didn’t become this absolutely ruthless, heartless person obsessed with success at any cost. Not at all. Along the way he saw what education could do to a human being. He discovered that.”

And this discovery, Dr. Udagama believes, was the legacy he most dearly wished to leave behind:

“Upon us is imposed the task of educating nearly all those who will lead the country in government, in business and in the professions … What is more, we have to train him to be a citizen and to assume his responsibilities as citizen quite independently of his employment or profession.” (The Road to Peradeniya)

Jennings drew richly from his experience as an undergraduate at Cambridge, and dreamt of creating the same glory at “Pera”. He envisioned a nationally-acclaimed library, enchanting museums, a world-famous campus, and more than anything else, an alma mater worth loving.

“The first public holiday after my arrival in Ceylon in March 1941 was Good Friday, and I seized the opportunity to pay my first visit to Peradeniya … Sitting on a tree stump on the bank of the Mahaweli Ganga … I began at last to see the magnificence of the scheme … There was no doubt about it … This could be a great university … In a few years’ time the view from the Nanu-Oya Bridge will be one of the most famous in the world … The whole would be framed in the tea-clad hills of Old Peradeniya, and above them the patina of the Hantane Ridge. No university in the world would have such a setting.”

Jennings’ vision for the University of Peradeniya which he left in January 1954, extended over thousands of years. Today, just over sixty hence, where, in a generation that hardly knows his name, are the lofty ideals of Pera’s “sage dreamers,” her progenitors?

“Jennings, walking these hills early and late

sheering past lovers, sending mischief scuttering,

benign headmaster; Adonis Rodrigo

first genial paterfamiliar dean,

Ludowyk, magister magsitrorum, perhaps

somewhat unwilling,

considering the metropolis; Attygalle, who whipped

the scientists and professionals here into the hills,

all are gone, most

dead. They barely lived to see

trees tall where the slopes were bare

debate sharpening into clamour

demagogues seeking beachheads into the future

pathetic dons disclaiming responsibility…”

(from “Elegy for Peradeniya” by Ashley Halpe)